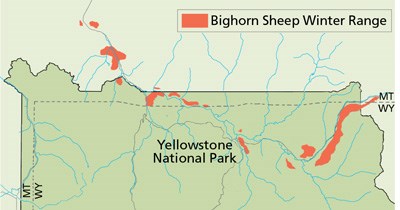

NPS / Diane Renkin Although widely distributed across the Rocky Mountains, bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) persist chiefly in small, fragmented populations that are vulnerable to sudden declines as a result of disease, habitat loss, and disruption of their migratory routes due to roads and other human activities. Between 10 and 13 interbreeding bands of bighorn sheep occupy steep terrain in the upper Yellowstone River drainage, including habitat that extends more than 20 miles north of the park. These sheep provide visitor enjoyment as well as revenue to local economies through tourism, guiding, and sport hunting. Mount Everts receives the most concentrated use by bighorn sheep year-round.

PopulationFrom the 1890s to the mid-1960s, the park’s bighorn sheep population fluctuated between 100 and 400. Given the vagaries of weather and disease, bighorn sheep populations of at least 300 are desirable to increase the probability of long-term persistence with minimal loss of genetic diversity. The count reached a high of 487 in 1981, but a keratoconjunctivitis (pinkeye) epidemic caused by Chlamydia reduced the population by 60% the following winter, and the population has been slow to recover. Although the temporary vision impairment caused by the infection is rarely fatal for domestic sheep that are fenced and fed, it can result in death for a sheep that must find its forage in steep places. During the 2018 survey, a total of 345 bighorn sheep were observed, including 214 in Montana and 131 inside Yellowstone National Park. This is slightly below the 10-year average of 358 sheep. Additionally, in 2018, lamb-to-ewe ratios of 20:100 were below the 10-year average (28:100), with very low lamb recruitment observed on the Cinnabar, Corwin, and Mt. Everts winter ranges. During 2005-2015, the population increased steadily. A decline occurred in 2015 related to an all-ages pneumonia event. In spite of the 2015 decline, overall bighorn sheep numbers in the northern Yellowstone remain substantially above the long-term average. Competition with Other SpeciesBighorn sheep populations that winter at high elevations are often small, slow-growing, and low in productivity. Competition with elk as a result of dietary and habitat overlaps may have hindered the recovery of this relatively isolated population after the pinkeye epidemic. Rams may be hunted north of the park, but the State of Montana has granted few permits in recent years because of the small population size. Although wolves occasionally prey on bighorn sheep, the population has increased since wolf reintroduction began in 1995. Longer-term data are needed to show whether sheep abundance may be inversely related to elk abundance on the northern range. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Montana State University, the US Forest Service, and several nongovernmental organizations are cooperating with the National Park Service to study how competition with nonnative mountain goats, which were introduced in the Absaroka Mountains in the 1950s, could affect bighorn sheep there. ResourcesBarmore, W.J. Jr. 2003. Ecology of ungulates and their winter range in Northern Yellowstone National Park, Research and Synthesis 1962–1970. Yellowstone Center for Resources. Buechner, H.K. 1960. The bighorn sheep in the United States, its past, present, and future. Wildlife Monographs May 1960(4):174. Fitzsimmons, N.N., S.W. Buskirk, and M.H. Smith. 1995. Population history, genetic variability, and horn growth in bighorn sheep. Conservation Biology 9(2):314–323. Geist, V. 1976. Mountain sheep a study in behavior and evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hughes, S.S. 2004. The sheepeater myth of northwestern Wyoming. In P. Schullery and S. Stevenson, ed., People and place: The human experience in Greater Yellowstone: Proceedings of the 4th Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, 2–29. Yellowstone National Park, WY: National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources. Krausman, P. R. and R. T. Bowyer. 2003. Mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis and O. dalli). In G.A. Feldhamer, B.C. Thompson and J. A. Chapman, ed., Wild mammals of North America: Biology, management, and conservation. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. White, P.J., T.O. Lemke, D.B. Tyers, and J.A. Fuller. 2006. Bighorn sheep demography following wolf reintroduction, Short Wildlife communication to Biology. White, P.J., T.O. Lemke, D.B. Tyers, and J A. Fuller. 2008. Initial effects of reintroduced wolves Canis lupus on bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis dynamics in Yellowstone National Park. Wildlife Biology 14(1):138–146.

Mammals

Home to the largest concentration of mammals in the lower 48 states. |

Last updated: April 18, 2025