|

About 8,000-10,000 years ago, 12 species of native fish, including Arctic grayling, mountain whitefish, and cutthroat trout, dispersed to this region following glacier melt. These native fish species provided food for both wildlife and human inhabitants. The distribution of native fish species was originally constrained by natural waterfalls and watershed divides. These landscape features provided a natural variation of species distributed across the landscape and vast areas of fishless water. At the time Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872, approximately 40% of its waters were barren of fish—including Lewis Lake, Shoshone Lake, and the Firehole River above Firehole Falls.

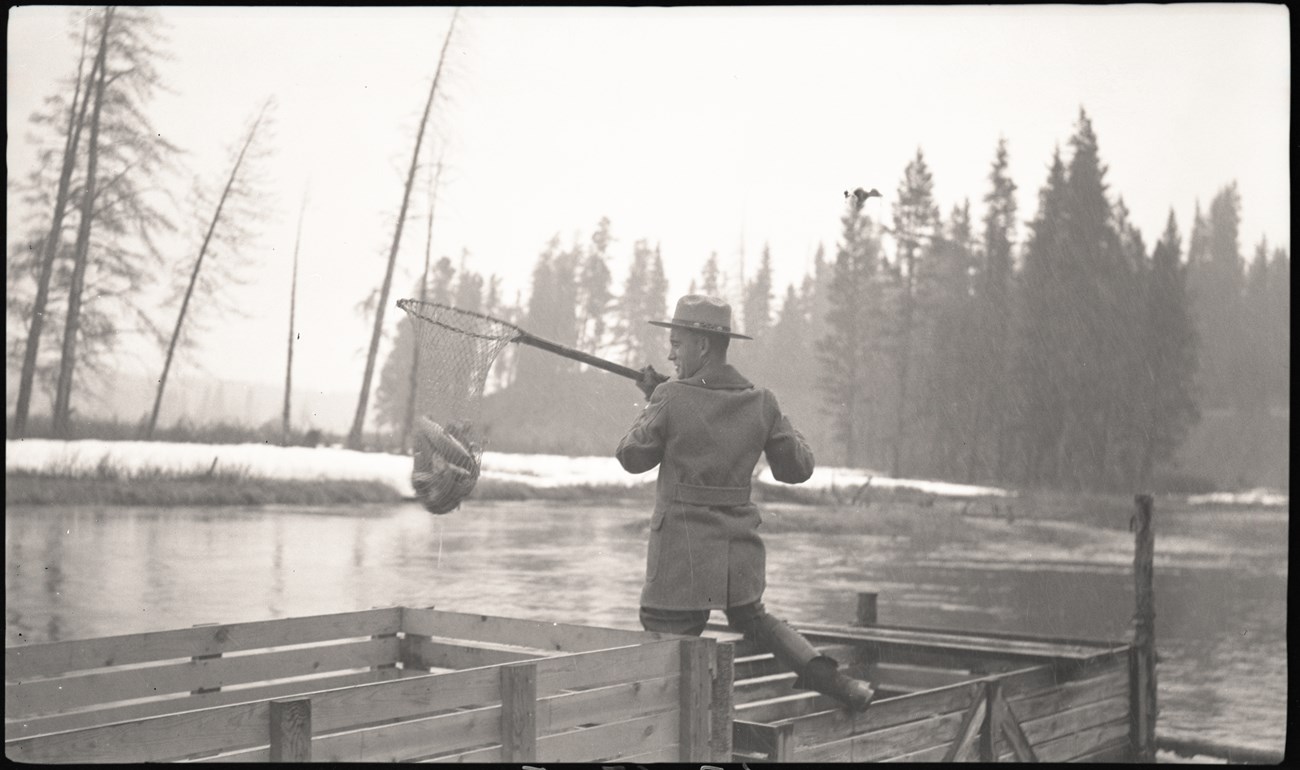

Early Fish ManagementCreated in 1872, Yellowstone National Park was, for several years, the only wildland under active federal management. Early visitors fished and hunted for subsistence, as there were almost no visitor services. At the time, fishes of the park were viewed as resources to be used by sport anglers and provide park visitors with fresh meals. Fish-eating wildlife, such as bears, ospreys, otters, and pelicans, were regarded as a nuisance, and many were destroyed as a result.

The stocking of nonnative fishes by park managers has had profound ecological consequences. The more serious of these include displacement of intolerant natives such as westslope cutthroat trout (O. clarki lewisi) and Arctic grayling (Thymallus arcticus); hybridization of Yellowstone (O. c. bouvieri) and westslope cutthroat trout with each other and with nonnative rainbow trout; and, most recently, predation of Yellowstone cutthroat trout by nonnative lake trout. Over the years, management policies of the National Park Service have drastically changed to reflect new ecological insights. Subsistence use and harvest orientation once guided fisheries management. Now, maintenance of natural biotic associations or, where possible, restoration to pre-Euro-American conditions have emerged as primary goals. Eighteen fish species or subspecies are currently known to exist in Yellowstone National Park; 12 of these are considered native (they were known to exist in park waters prior to Euro-American settlement), and five are introduced (nonnative). Today, about 40 lakes have fish; others were either not stocked or have reverted to their original fishless condition.

Yellowstone Lake Fish HatcheryHatchery operations at Yellowstone Lake became part of this undertaking when fish hatched from Yellowstone’s trout were used to stock waters in the park and elsewhere, sportfishing was promoted to encourage park visitation, and satisfying a recreational interest took precedence over protection of the park’s natural ecology. Built in 1930 by the National Park Service, the hatchery’s log-framed design is also an example of the period of rustic architectural design in national parks.The hatchery was thought to be among the most modern in the West. The main room was outfitted with tanks and raceways for eggs, fingerlings, and brood fish taken from 11 streams that flowed into the lake. Small fry were fed in three rectangular rearing ponds in a nearby creek until they were ready for planting. Superintendent Horace Albright explained that the hatchery had also been designed with visitor education in mind, by making it possible “to take large crowds through the building under the guidance of a ranger naturalist without in any way impairing the operations of the Bureau of Fisheries." Yellowstone was the largest supplier of wild cutthroat trout eggs in the United States, and its waters received native and nonnative fish. A rift developed, however, between the federal fish agencies and the National Park Service, which began moving away from policies that allowed manipulation of Yellowstone’s natural conditions. In 1936 Yellowstone managers prohibited the distribution of nonnative fish in waters that did not yet have them and opposed further hatchery constructions in the park’s lakes and streams. After research showed that it impaired fish reproduction, egg collection was curtailed in 1953. Four years later, the fish hatchery ceased operations and the US Fish and Wildlife Service transferred ownership of the building to the National Park Service. Official stocking of park waters ended by 1959. Today, vegetation and stream flow have largely reclaimed the rearing ponds on Hatchery Creek, but their outlines can still be detected, and the most serious results of fish planting are irreversible. Nonnative fish can alter aquatic ecology through interbreeding or competition with native species. Although its condition has deteriorated, the hatchery building has changed relatively little. Nearly all of the exterior and interior materials are original to the building or have been repaired in kind. Now used as a storage facility, it is the primary structure of the nine buildings in the Lake Fish Hatchery Historic District, which was listed on the National Register in 1985. Native Fish Restoration Efforts While the Yellowstone cutthroat trout is historically a Pacific drainage species, it has naturally traveled across the Continental Divide into the Atlantic drainage. One possible such passage in the Yellowstone area is Two Ocean Pass, south of the park in the Teton Wilderness.Habitat remains pristine within Yellowstone National Park, but nonnative fish species pose a serious threat to native fish. In Yellowstone Lake, lake trout are a major predator of cutthroat trout. In other waters, brown, brook, and rainbow trout all compete with cutthroat trout for food and habitat. Rainbow trout pose the additional threat of hybridizing with cutthroat trout.

Lamar River Because no barriers to upstream fish migration exist in the mainstem Lamar River, descendants of rainbow trout stocked in the 1930s have spread to many locations across the watershed and hybridized with cutthroat trout. Genetic analysis indicates that cutthroat trout in the headwater reaches of the Lamar River remain genetically unaltered. To protect the remaining Yellowstone cutthroat trout, the NPS has implemented a selective removal approach. A mandatory kill fishing regulation on all rainbow trout caught upstream of the Lamar River bridge was instituted in 2014. Currently regulations state that all nonnative fish and identifiable cutthroat x rainbow trout hybrids upstream of Knowles Falls must be killed. Selective removal by electrofishing has been conducted annually through the Lamar Valley since 2013. In 2019, 7% of fish sampled during electrofishing surveys upstream of the Lamar River Canyon were classified as rainbow or hybrid trout. This low percentage is a stark contrast to work conducted downstream of the Canyon. In 2015, 136 fish were sampled downstream of the Lamar River bridge. Based on field identification, 48% were Yellowstone cutthroat trout, 19% were rainbow trout, and 31% were hybrids. The majority of these fish were tagged with radio transmitters or passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags as part of an ongoing research project to determine if Yellowstone cutthroat, rainbow, and hybrid trout are using the same areas to spawn and spawn timing and to inform management actions. Slough Creek In Slough Creek, rainbow-cutthroat trout hybrids have been found with increasing frequency over the past decade. Unlike the Lamar River, Slough Creek is smaller, and a barrier to upstream fish movement has been constructed. With a barrier in place and rainbow trout no longer allowed passage into the system, existing rainbow and hybrid trout can be effectively managed with angling and electrofishing removal. Soda Butte Creek Brook trout became established in Soda Butte Creek outside of the park boundary and spread downstream into park waters in the early 2000s. Initially, brook trout were isolated in headwater reaches by a chemical barrier created by mine contamination upstream of Cooke City, Montana. When the mine tailings were capped and water quality improved, brook trout passed downstream and began to negatively impact the cutthroat trout. For nearly two decades, interagency electrofishing surveys were enough to keep brook trout populations low but did not prevent range expansion. Over time, brook trout spread downstream and became a threat to the Lamar River. In addition, rainbow trout hybridization continued to be identified in cutthroat trout upstream of Ice Box Canyon. In 2013, Ice Box Falls was modified to be a complete barrier to upstream fish movement, preventing further rainbow trout introgression. Rotenone, a fish toxin, was then used to remove all nonnative fish from the system. Nearly 450 brook trout were removed during the chemical treatment in 2015. Only two brook trout were collected from Soda Butte Creek during a second treatment in 2016. From 2017 through 2021, eDNA sampling as well as electrofishing surveys found no evidence of brook trout in the system. This is a good indication that a complete kill was achieved in the drainage. However, in 2022, following historic flooding in the system, brook trout were discovered. In 2023, NPS, USFS, and MTFWP fisheries biologists worked to determine the spatial extent of the invasion, develop an action plan, and ultimately chemically treat Soda Butte Creek from the Yellowstone National Park boundary downstream to Ice Box Falls. Prior to chemical treatment, crews electrofished the stream and collected over 1,000 Yellowstone cutthroat trout and moved them to a holding location outside of the treatment area. Chemical treatment took place on August 16, and the stream was clear of chemical on August 17. The salvaged YCT were released back into the waters of Soda Butte Creek. The treatment appears to have been a success as all sentinel fish held in cages through the treated waters died within a few hours of receiving chemical. Continued monitoring of the system via electrofishing and eDNA sampling will take place over the next several years to confirm that all brook trout have been eliminated from Soda Butte Creek. Elk Creek Complex There is a natural cascade barrier in Elk Creek just upstream from its confluence with the Yellowstone River. The cascade prevented fish from naturally populating the system, so the Elk, Lost, and Yancey creeks complex of streams (Elk Creek Complex) was fishless when first stocked with cutthroat trout in the early 1920s. In 1942, the streams were stocked with brook trout, eventually resulting in the complete loss of cutthroat trout. To restore YCT to the system, the Elk Creek Complex was treated with rotenone annually from 2012 to 2014 to remove the brook trout population. Once clear of brook trout, reintroduction of native Yellowstone cutthroat trout began. Antelope and Pebble creeks provided fish for restocking in October 2015. Additional stocking took place in 2016 and 2017. Natural reproduction was also documented in 2017 during electrofishing surveys. Semi-annual surveys of the Elk Creek Complex show that YCT are well established in the system and continue to naturally reproduce. No brook trout have been detected since the 2014 rotenone treatment. One of the goals of the park’s 2010 Native Fish Conservation Plan is to restore fluvial grayling to approximately 20% of their historical distribution. The upper reaches of Grayling Creek are considered the best site for immediate fluvial grayling restoration. Near the park boundary, a small waterfall exists in the creek (which flowed directly into the Madison River prior to the construction of Hebgen Dam in 1914).

The Grayling Creek restoration project aims to establish Arctic grayling and westslope cutthroat trout to 95 kilometers (59 miles) of connected stream habitat in one of the most remote drainages in the species historic range within Yellowstone. During summer 2013, the waterfall was modified to prevent upstream movement of fish into the system. During August 2013, a crew of 27 biologists from Yellowstone National Park, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Gallatin National Forest, Turner Enterprises, and US Fish and Wildlife Service treated the stream segment with piscicide to remove all fish. A second treatment took place in 2014. Restocking the Grayling Creek watershed with native fluvial Arctic grayling and WCT began in 2015 and continued through 2017. The effort included moving approximately 950 juvenile and adult WCT to the lower reaches of Grayling Creek, above the project barrier. In addition, 54,200 WCT eggs and 210,000 fluvial grayling eggs were placed in remote-site incubators throughout the upper watershed. In 2018, park biologists and Montana State University researchers began to evaluate the success of reintroduction efforts on upper Grayling Creek. Preliminary results suggest that WCT are slowly repopulating the system, but grayling are struggling to establish a self-sustaining population. From 2017–2021, park managers worked on a native fish restoration project in the upper Gibbon River drainage including Grebe, Wolf, and Ice lakes, and the Gibbon River upstream of Virginia Cascades. After removing nonnative species, biologists stocked more than 100,000 westslope cutthroat trout embryos and fish, and 170,000 Arctic grayling fry. An additional 7,000 grayling fry were stocked in Grebe Lake in 2023. Angling has been highly successful for both species post-stocking, and natural reproduction was first documented for westslope cutthroat trout in 2022 and for Arctic grayling in 2023. Downstream dispersal of both species indicates the upper Gibbon River may serve as a fish source for the lower Gibbon and Madison rivers. Sites were established in 2023 to monitor native fish recovery and fish captured by electrofishing and angling were equipped with orange Floy tags to estimate abundance, survival, and movement patterns. Anglers who recapture tagged fish in Yellowstone are encouraged to report tag numbers and locations to assist with monitoring efforts. Native species restoration depends on secure brood sources. A brood should be accessible, safe from contamination, self-sustaining, genetically diverse, abundant, of traceable origin, and pose no risk to existing wild populations.

In the park, genetically pure WCT only persisted in one tributary in the Madison River drainage (now called Last Chance Creek) and in the Oxbow/Geode Creek complex where they were introduced in the 1920s. In 2006, Yellowstone began efforts to restore WCT in East Fork Specimen Creek and introduce them into High Lake by constructing a fish barrier, removing nonnative fish, and stocking genetically pure WCT. In 2016 and 2018, surveys conducted throughout East Fork Specimen Creek indicated a naturally reproducing population of WCT, with all fish appearing healthy. Unfortunately research in 2019 revealed that hybridized fish have moved upstream of the constructed barrier, threatening the restored portion of the creek. The long-term goal for this watershed is to integrate East Fork Specimen Creek into a larger WCT restoration project that includes the North Fork to improve the resilience of this isolated population to natural threats. In 2021, the lower reaches of the East Fork Specimen Creek were chemically treated to remove all hybridized fish from this section of stream. A range expansion project was conducted in Goose Lake and two other small, historically fishless lakes in the Firehole drainage. Nonnative fish removal was conducted in 2011 and staff stocked fry from 2013 to 2015. The long-term project goal is to one day use this pure WCT population as a brood source, providing offspring for restoration projects elsewhere within the upper Missouri River system. While WCT have been found in Goose Lake in low numbers, stocking efforts in the other two lakes have proven unsuccessful. Another range expansion project is the upper Gibbon River. In 2017, native fish restoration began on the upper portion of Gibbon River, above Virginia Cascades. This project encompasses more than 21 stream miles and 232 lake acres (Wolf, Grebe, and Ice lakes). Since fall of 2017, park biologists have introduced approximately 75,000 WCT and 170,000 Arctic grayling to Wolf, Grebe, and Ice lakes and surrounding tributaries. Fish removal continued on the upper Gibbon River from 2018 through 2020 between Virginia Cascades and Wolf Lake. Removal of nonnative fish in this section was completed in 2020. Future restoration projects for WCT and Arctic grayling are proposed for North Fork Specimen and Cougar creeks. Once completed, native fish will be restored to an additional 61 km of stream waters. Gillnetting Lake TroutIn 1995, after confirming lake trout were successfully reproducing in Yellowstone Lake, the NPS convened a panel of expert scientists to determine the likely extent of the problem, recommend actions, and identify research needs. The panel recommended that the park suppress lake trout to protect and restore native cutthroat trout. The panel also indicated that direct removal efforts such as gillnetting or trapnetting would be most effective but would require a long-term, possibly perpetual, commitment.As initial gillnetting efforts expanded, the number of lake trout removed from the population also increased. This suggested the lake trout population was continuing to grow. In 2008 and 2011, scientific panels were convened to re-evaluate the program and goals. The panel concluded netting is still the most viable option for suppressing lake trout. Both reviews also indicated a considerable increase in suppression effort would be needed over many years to collapse the lake trout population. Starting in 2009, the park contracted a commercial fishing company, to increase the take of lake trout through gillnetting. From 2011 to 2013, they also used large, live-entrapment nets that allow removal of large lake trout from shallow water while returning cutthroat trout to the lake with little mortality. Discovery of New Species in Yellowstone LakeOn August 22, 2019, a gill net set in 158 feet of water northeast of Stevenson Island captured one fish of a new species not previously known to exist in Yellowstone Lake. This was a 3-year-old immature female cisco (Coregonus artedi). Based on otolith microchemistry, it likely hatched in Yellowstone Lake. Undoubtedly this species was illegally introduced to Yellowstone Lake, as the nearest source populations are in northern Montana and Minnesota. There are no existing waterways between Yellowstone Lake and any known cisco populations.In its native range, cisco are a preferred prey item for lake trout where the two species overlap. They prey mostly on aquatic invertebrates and tend to reside at mid-water depths. Fortunately, despite miles of gill nets, some specifically targeting cisco habitat, surface tows for larvae, eDNA sampling at 24 sites around the lake, and examination of thousands of lake trout stomachs, no other cisco have been found in Yellowstone Lake.Fish Management ResearchIn 2010, Yellowstone developed the Native Fish Conservation Plan. This adaptive management plan guides efforts to recover native fish and restore natural ecosystem functions based on scientific assessment.In 2011, the National Park Service and the US Geological Survey launched a movement study to target lake trout embryos in spawning beds and identify general and seasonal movement patterns. The results helped gillnet operators to target lake trout more efficiently. In 2013, NPS and Montana State University conducted a mark-recapture study of lake trout in Yellowstone Lake. To estimate population size, 2,400 lake trout were tagged and released back into the lake. More than 5% of tagged fish were recaptured within the same fishing season. Results produced an estimate of the number of lake trout present in the lake: 367,650 fish greater than 210 millimeters (8.3 in.) long. The mark-recapture study also helped estimate rates of capture for four size classes. This effort removed 72% of lake trout 210–451 millimeters (8.3–17.8 in.) in length, 56% for fish 451–541 millimeters (17.8–21.3 in.) long, 48% for fish 541–610 millimeters (21.3–24.0 in.) long, and 45% for fish more than 610 millimeters (>24.0 in.) long. These results supported previous estimates and highlighted the difficultly in catching older, mature lake trout, which eat the most native cutthroat trout and have the highest reproductive success. In 2022, we caught three lake trout which had originally been tagged in 2013 as part of this study. More Information

|

Last updated: September 9, 2025