When President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act on August 25, 1916, Yellowstone National Park was 44 years old. For more than four decades, Yellowstone had been an ongoing experiment in federal resource management. Leadership in the park was unstable from the beginning. The early civilian superintendents had no blueprint to guide them in their positions and often had to deal with competing business and government interests. The unregulated expansion of industry and corruption in US politics made the work of the early superintendents even more difficult. After the US Cavalry took over management and protection of the park in 1886, the work of the superintendents did not get any easier. The army superintendents were plagued by many of the same issues that had plagued the civilian superintendents. Additionally, the cavalry units stationed in the park were changed so frequently, the army superintendents often had little time to make any real impact. Despite this, the administrative offices of the park did see some continuity during the Army Era.

In 1894, Acting Superintendent Captain George S. Anderson hired a civilian named Chester A. Lindsley to work as a clerk in the superintendent’s office. Because Lindsley was not enlisted in the US Army, he was not required to leave when Anderson’s cavalry unit was reassigned in 1897. So, when Captain Anderson’s replacement, Captain Samuel Young, took over in June 1897, Lindsley stayed on and worked under him as well. In fact, Lindsley would work as a clerk for every superintendent from the time of his hiring in 1894 until October 1916. Because of the continuity Lindsley was able to provide, he quickly became an invaluable member of each superintendent’s staff. Because of the knowledge, experience, and insight he gained over the three decades he worked for the park’s administration during the Army Era, he was an obvious choice to hold the position of superintendent when the army left and the National Park Service took over in the fall of 1916.

Chester Lindsley became the first leader of the park under the newly formed National Park Service in October 1916. Horace Albright, who in 1916 was an assistant attorney at the Department of the Interior and working alongside Stephen Mather, visited Yellowstone in September of that year in order to ensure the transition from army to park service would be a success, deliver instructions to Lindsley from the nascent National Park Service offices in Washington D.C., and consult with Lindsley on a number of different issues regarding the park on which Albright needed clarity. After spending a few days with Lindsley, Albright was confident that Lindsley, a “very capable, knowledgeable fellow,” would “carry out the instructions [Albright] was leaving with him and would manage the park efficiently.” Lindsley was initially aided in the transition by Colonel Lloyd Brett, the last military superintendent, but Brett was gone from Yellowstone by the end of October 1916. For the next several months, Lindsley worked diligently to ensure the park was managed in accordance with the orders coming from Washington D.C. He was aided by a small force of civilian rangers. These first rangers were actually discharged cavalrymen who had formerly served at Yellowstone in the final years of the Army era and had been hand selected by Albright and Colonel Brett. Through the first half of 1917, Lindsley and his elite force of rangers served the park and its visitors well and represented the National Park Service with dignity. However, pressure from local citizens and from United States congressmen in 1917 forced Lindsley and the National Park Service to make some changes.

When the US Congress created the National Park Service, they didn’t provide any immediate funds to operate the new agency’s office in Washington. Albright had to appear before the Senate and House Appropriations Committees to ask for money. The Senate committee members had no issue with Albright’s request, but the chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, John J. Fitzgerald, was not so easily persuaded. Fitzgerald was so displeased with the specifics of Albright’s request, he inserted a clause into the appropriations bill for the fiscal year 1918 that was passed in the spring of 1917. The clause stated that unless the US Army was once again given command of Yellowstone, the National Park Service would receive no appropriations for the fiscal year.

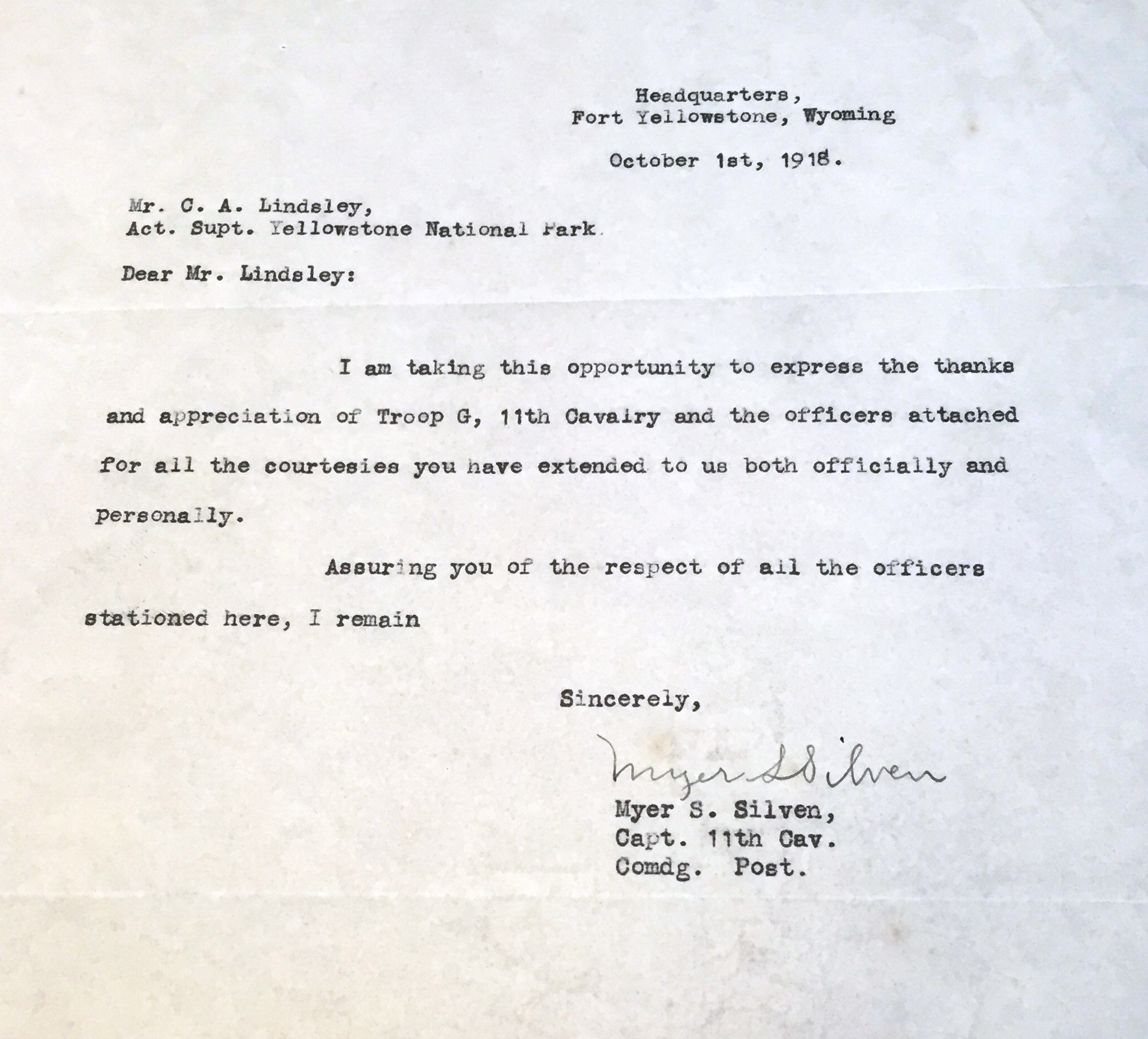

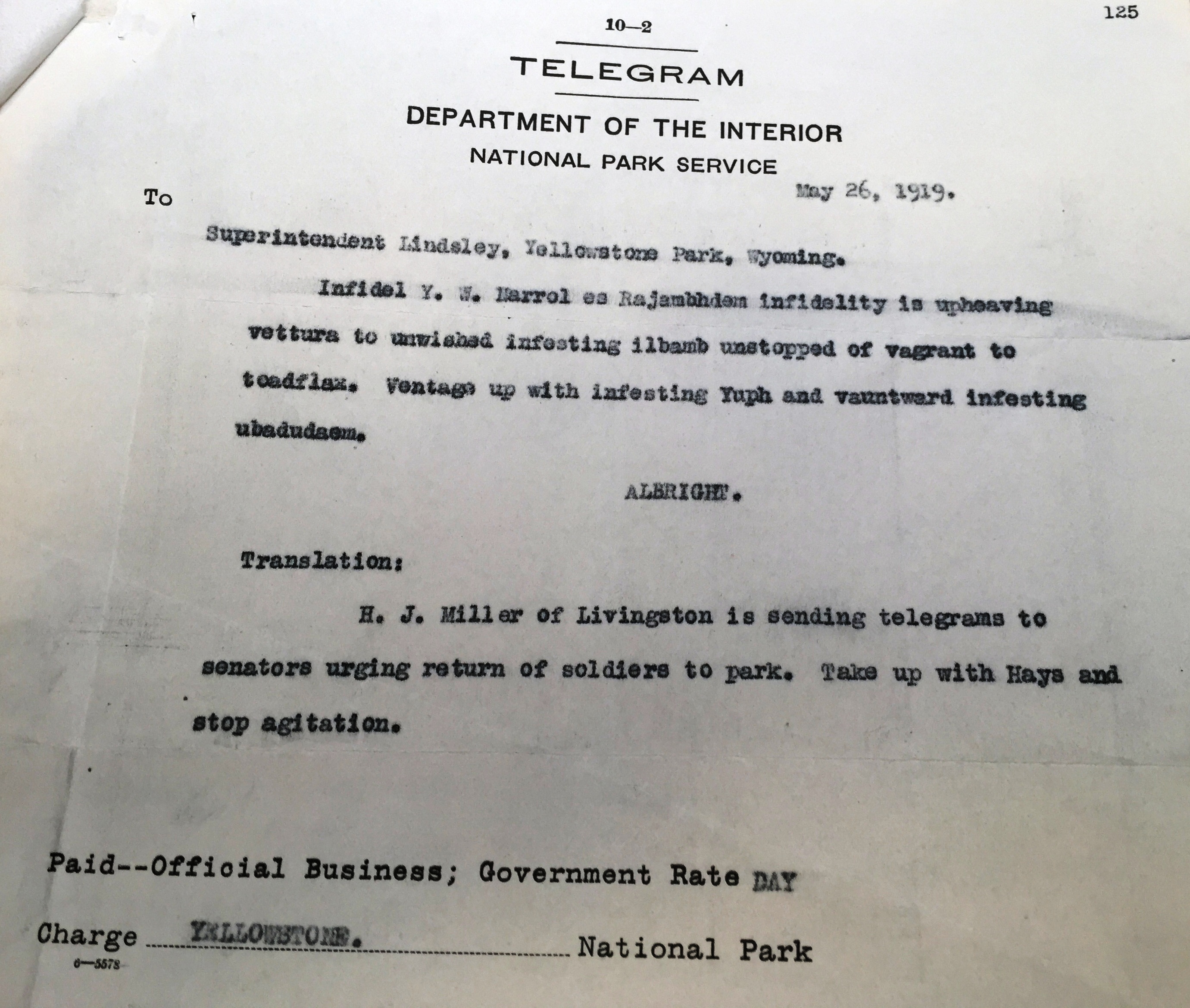

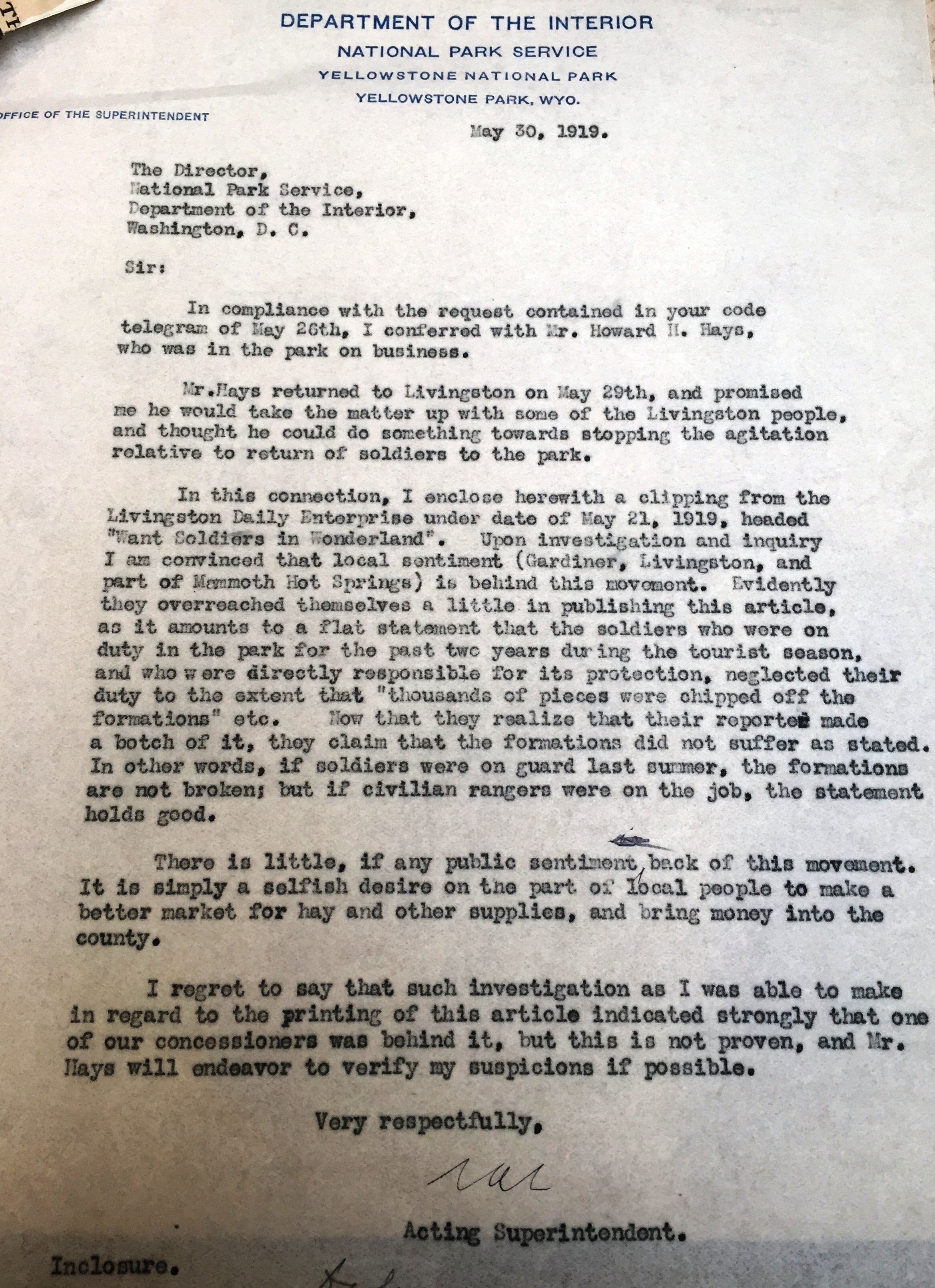

On July 1, 1917, the US Army returned to Yellowstone. The hand-picked civilian ranger force was replaced by mostly new draftees who were rotated out so often, they barely had any time to get to know the park. Albright, who by 1917 was acting director of the National Park Service, did the best he could to ensure Lindsley’s authority was maintained. Albright’s reassurances in the summer of 1917 that the army’s latest command was “strictly temporary” did little to assuage Lindsley’s sorrow. Despite his despair, Lindsley served the park with honor and dignity during the army’s second brief stay at Yellowstone. After the army left permanently in October 1918, Lindsley resumed his role as superintendent. He held the position until June 1919, when Albright was appointed the first official superintendent of Yellowstone.

Despite the fact that history remembers Albright as the first superintendent of Yellowstone, Chester Lindsley’s time as superintendent of Yellowstone should not be overlooked. He served Yellowstone well and would continue to do so until he retired in 1935. Lindsley should be remembered as a superintendent, just as all of his predecessors should. Men like Nathaniel Langford, Captain Moses Harris, and Chester Lindsley all presided over the world’s first national park and contributed to the park’s continued survival.

Direct Quotations Sources:

Horace Albright, Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years (University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), pg. 150

All correspondence can be found in Folder “125 Troop Removal, 1918-1919”, Box 015, Series 06, RG 10Management & Accountability Records, Yellowstone National Park Archives