In “An Act to set apart a certain Tract of Land lying near the Head-waters of the Yellowstone River as a public Park,” Congress gave the Secretary of the Interior exclusive control over the area that would become Yellowstone National Park. According to Aubrey Haines, however, “it seems to have been understood almost from the beginning that someone would be placed in direct charge.” Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano decided he wanted to appoint someone who had been a part of the Washburn Expedition of 1870. Different members of the expedition were suggested, including Truman Everts, but Congress had not provided any appropriation for the future head of the park’s salary and had given no indication that they might do so, which made the position unattractive to many. Secretary Delano made his decision in the early days of May 1872 and notified his appointee, Nathaniel P. Langford, by letter. Langford received the notification on May 10 and accepted the job, despite the fact that he would be provided no salary.

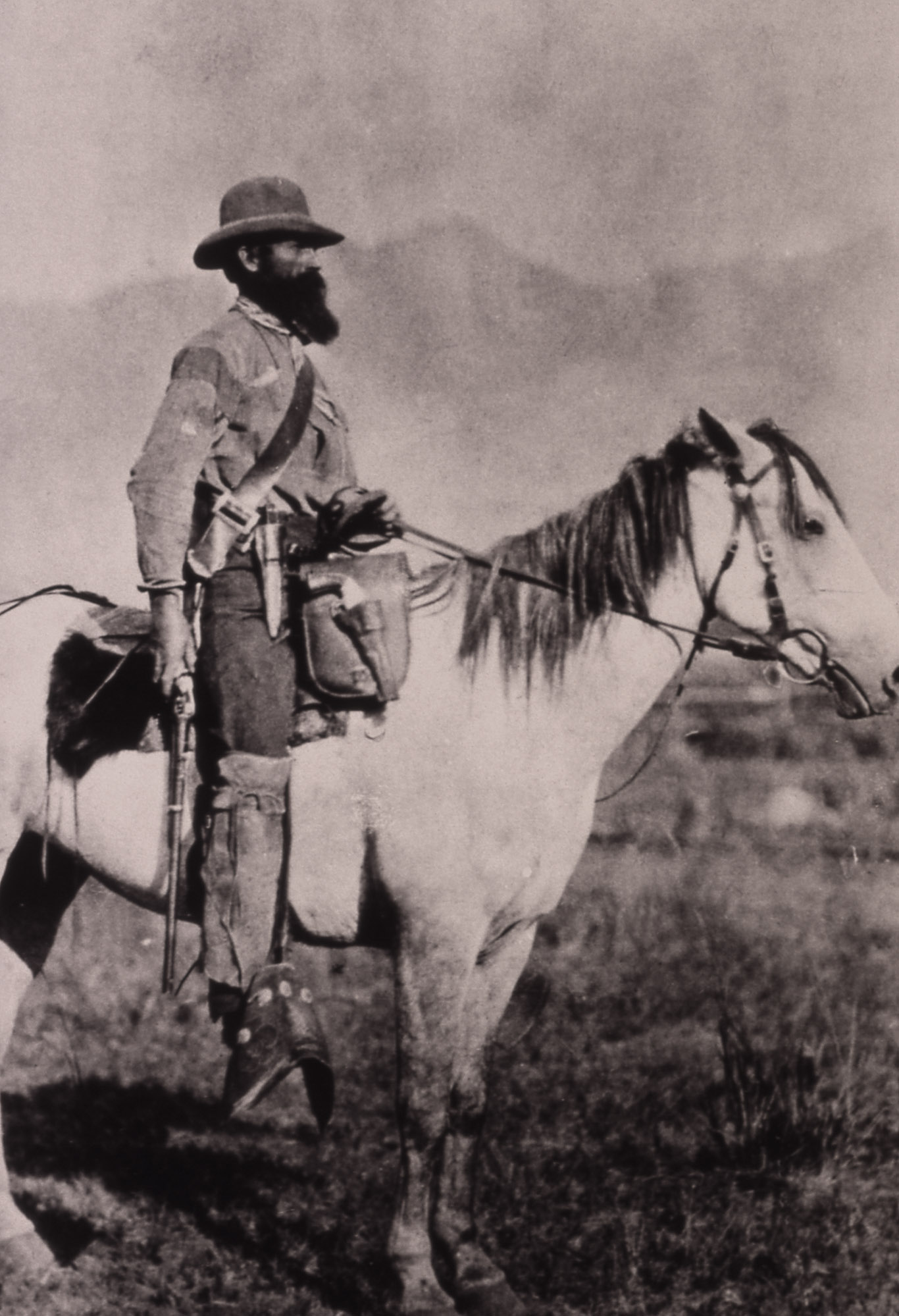

When Nathaniel Langford was appointed Yellowstone’s first civilian superintendent, he already had many ties to the region. In 1872, he was living in Helena, the capital of the Montana territory, and working as federal bank examiner for the territories and Pacific Coast states. He had been in Montana since 1862, when he set out from Minnesota with a large wagon train heading west, seeking gold. By the spring of 1870, he had held and lost a position as tax collector for Montana and an appointment as governor of the territory and he had failed in at least one business venture. Unemployed, Langford “found a job that took him back to Montana and probably had much to do with getting the Yellowstone exploration off dead-center.” In June of 1870, Langford and railroad financier Jay Cooke met at Cooke’s home in Philadelphia. There, they agreed that an expedition of Yellowstone could be the gold mine Langford had long sought and he returned to Montana as nominal employee of the railroad which Jay Cooke financed, the Northern Pacific.

Langford spent most of the summer of 1870 dreaming up an expedition and finding partners to join him on his publicity campaign. The expedition, which departed the Bozeman area on August 22, was led by General Henry D. Washburn. The expedition lasted roughly a month and when Langford returned to Helena, he set about the task that had been given to him by Jay Cooke. For the next several months, Langford supplied accounts of the expedition to newspapers and lectured across the country as part of a publicity tour for the Northern Pacific Railroad. At a lecture Langford gave in Washington D.C. on January 19, 1871, a man in the audience found so much inspiration in Langford’s words, he quickly became one of the most important figures in the history of Yellowstone. Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden was head of the U.S. Geological Survey of the territories and used his considerable connections in Congress to get an appropriation that would allow an expedition to explore and investigate the sources of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers in the summer of 1871. Less than 6 months after the Hayden Expedition left Yellowstone, Congress created the world’s first national park.

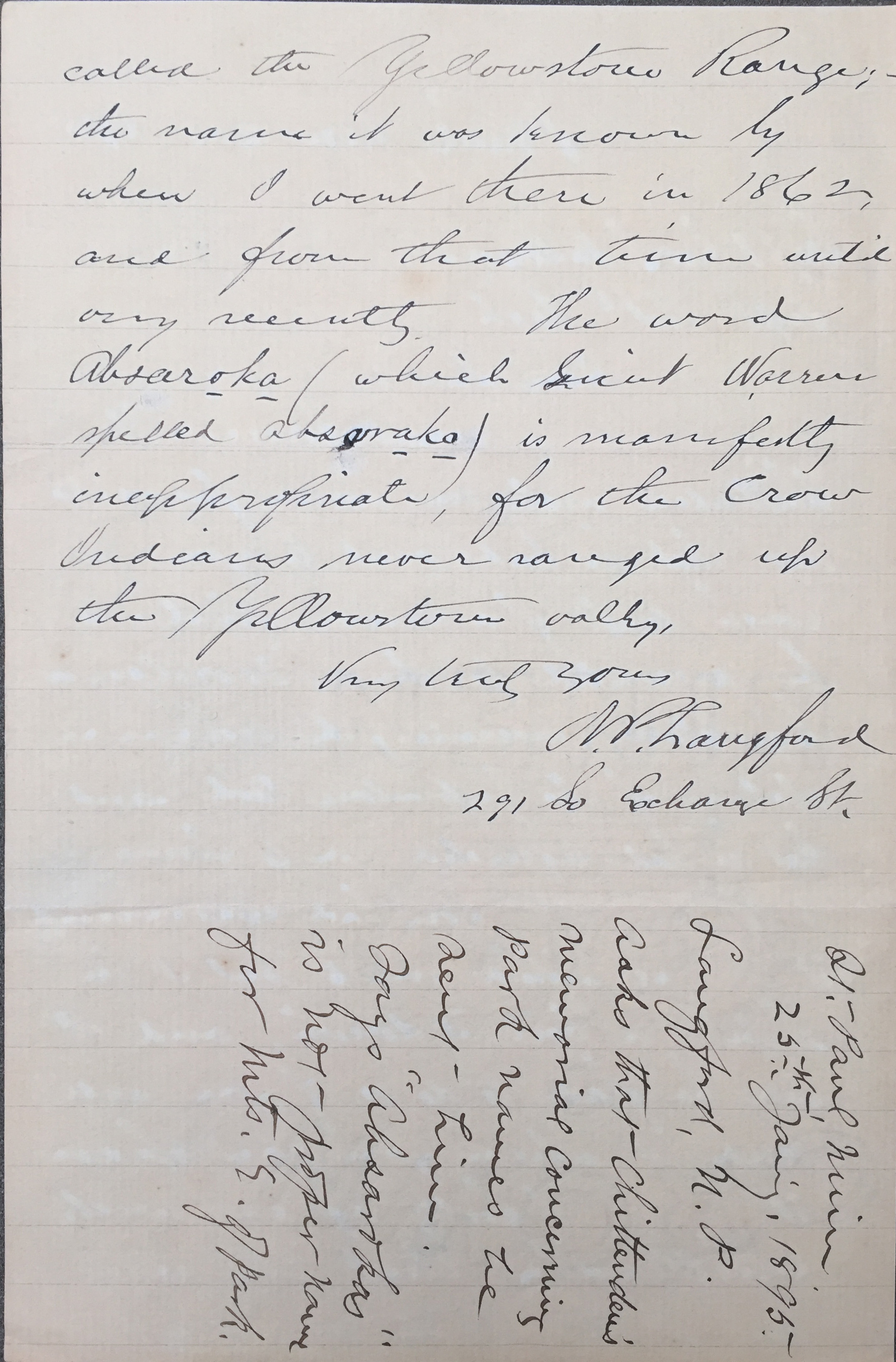

As head of that first national park, Langford joined the Hayden Survey of 1872 in order to thoroughly survey the park. In the same letter in which he accepted the position, he noted that the survey should be done before any commercial land leases could be granted. He also asked Secretary Delano what powers his position as superintendent gave him and asked whether he could be authorized to build at least public house for tourists. He also asked for the authorization to make “all necessary regulations…for the protection of the rights of visitors, and establishment of such rules as will conduce to their comfort and pleasure.” The report he wrote at the conclusion of the 1872 Hayden Survey indicated a massive need for roads in the park. He also believed that Congress should act quickly to make all the improvements he thought the park needed. The report would be his first and last on the area.

By 1875, men like Philetus T. Norris and Captain William Ludlow were commenting on the rampant abuses and massive slaughters of wildlife that were going on in the park. The comments of Norris and Ludlow and others also focused on Langford’s ineffectiveness as superintendent. Records show that Langford visited the park only once after 1872. In addition to his relative lack of concern for the resources he was charged with protecting, Langford also denied every proposal and application of those seeking to establish businesses in the park. According to Aubrey Haines, Langford was probably denying all proposals in hopes that the rail beds of the Northern Pacific would eventually make their way to Yellowstone.

By 1877, Langford had done so little to improve the park or protect its resources, three different Secretaries of the Interior had grown annoyed and irritated with him. Secretary Zachariah Chandler replaced Columbus Delano in October 1875. In March of 1877, Carl Schurz was appointed head of the Department of the Interior. Secretary Schurz had been in office one month before he removed Langford from his position on April 18, 1877.

It’s easy to criticize Langford for his lack of leadership and his obvious conflicts of interest. He had direct ties to a railroad company trying to make money off the park. He also had a full time job which kept him busy and away from the park, even if he had wanted to be there. While valid, it is also important to remember that he was the first head of the world’s first national park. He had no manual, guidebook, or mentors to show him or teach him how to protect and preserve Yellowstone and keep it open “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” He also lacked the support of the body which created the park. Although Langford petitioned them more than once for funds, Congress did not begin appropriating money for the management of the park until 1878. Thankfully, the park dream was kept alive by men like Captain Ludlow, who made a suggestion in 1875 that would eventually alter the future of the park forever.

Quotation & Direct Citation Sources:

-Aubrey L. Haines, The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park, vol. 1, 1977, pages 180, 105, 214

-Nathaniel Langford, May 10, 1872 Letter, original held by NPS, reprinted in full in Louis C. Cramton, Early History of Yellowstone National Park and Its Relation to National Park Policies, 1932, page 38, and in Haines, Yellowstone Story, vol. 1, 180-181