|

Note: This article is split into four parts. Click the links at the bottom of each page to continue to the next section. Table of Contents

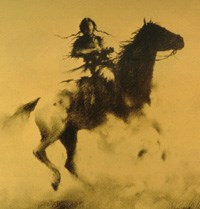

NPS Image IntroductionAmong the numerous engagements between American Indians and the U.S. Army in North Dakota, several encounters occurred near modern Theodore Roosevelt National Park in western North Dakota. Two notable campaigns were those of General Alfred Sully in 1864 and General Alfred Terry and Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer in 1876, both against the Sioux. Sully's 1864 CampaignThe first wave of hostilities in western Dakota was rooted a year earlier in Minnesota. In 1862 and 1863, members of several bands of Sioux including the Sisseton, Wahpeton, and Santee attacked numerous targets near the Minnesota River in south-central Minnesota. In the fighting, more than 600 Minnesotan civilians and army personnel were killed. Partly in response to these attacks known as the Minnesota Sioux Uprising, and despite the Civil War raging elsewhere in the United States, the U.S. Army retaliated against the Sioux in 1863 and 1864 against many groups of Sioux both responsible and not involved in the hostilities in Minnesota. Brigadier General Alfred Sully led the U.S. Army in its campaign in the western portion of the Dakota Territory in 1864. Fanny Kelly, a white American, was captured by the Sioux in a raid in the summer of 1864 prior to Sully’s campaign. Her captors were in turn pursued by Sully. Kelly’s account offers an interesting perspective of the Sioux at that time, although she confuses many of the details in her narrative. “The Indians felt that the proximity of the troops and their inroads through their best hunting-grounds would prove disastrous to them and their future hopes of prosperity, and soon again they were making preparations for battle,” she wrote. In July of 1864, General Sully led two brigades – approximately 2,200 men from Iowa, Minnesota, and Dakota – to the Killdeer Mountains, about twenty miles southeast of today’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park North Unit. There, a village of several bands of Sioux, about 8,000 people all together, were encamped. Sully dismounted his troops into a parallelogram formation and advanced on the village on the afternoon of July 28, 1864. Warriors led by Sitting Bull, Gall, and Inkpaduta sparred with Sully’s formation to little effect as the army advanced toward the village of 1,600 lodges. For warriors like Sitting Bull, it was the first battle in which they experienced cannons and a large number of guns. Fanny Kelly, who observed the battle from among the Sioux women and children hurriedly retreating from Sully’s troops, recalled, “General Sully’s soldiers appeared in close proximity, and I could see them charging on the Indians, who, according to their habits of warfare, skulked behind trees, sending their bullets and arrows vigorously forward into the enemy’s ranks.” Lt. David Kingsbury recorded his perspective of the battle from the other side of the field. “The Indians made repeated charges at the full speed of their ponies, keeping up meanwhile their unearthly yelling. In these charges many of them were killed, while no casualties occurred on our side.” Once within artillery range, Sully pounded the village with two mountain howitzers until sundown, holding his troops back to avoid hand to hand combat. The village was abandoned. The next day, Sully’s troops destroyed the large stores of food, tipis, and supplies that had been left behind. Lt. Kingsbury reported “The amount of supplies, including pemmican, jerked buffalo meat, dried berries, and buffalo robes, that was burned could not be estimated.” “We had left, in our compulsory haste,” Fanny Kelly recalled, “immense quantities of plunder, even lodges standing, which proved immediate help, but in the end a terrible loss. General Sully with his whole troop stopped to destroy the property, thus giving us an opportunity to escape, which saved us from falling into his hands, as otherwise we inevitably would have done.” The several bands of Sioux split up after the fight. The Sans Arcs, with Fanny Kelly, fled west into the badlands, eluding Sully for the moment but parting with much of their supplies and energy. “On, and still on, we were forced to fly to a place known among them as the Bad Lands... The desolate, ruinous scene might well represent the entrance to the infernal shades… I was startled by the strange and wonderful sights,” recalled Fanny Kelly. “The terrible scarcity of water and grass urged us forward, and General Sully’s army in the rear gave us no rest.” |

Last updated: January 27, 2025