Mission San José de Tumacácori

Tumacácori National Historical Park, Arizona

Coordinates: 31.562638, -111.050008

#TravelSpanishMissions

Discover Our Shared Heritage

Spanish Colonial Missions of the Southwest Travel Itinerary

Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Photo by Ammodramus. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

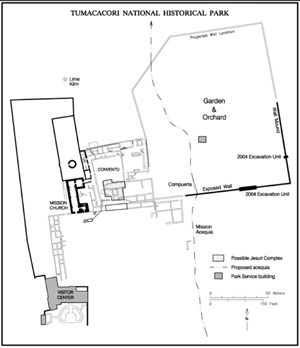

NPS map. Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Plan Your Visit

Tumacácori National Historical Park, a unit of the National Park System is located 45 miles south of Tucson, AZ off exit 29 on I-19. The visitor center for the Tumacácori National Historical Park is located at 1891 East Frontage Rd., Tumacácori, AZ and is open 9:00am to 5:00pm daily, except Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. Click here for the National Register of Historic Places file: text and photos. There is an admission fee. For more information, visit the National Park Service Tumacácori National Historical Park website or call 520-377-5060. The Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail passes through Tumacácori; please visit their website for information on sites along the 1,200-mile trail that connects history, culture, and outdoor recreation across 20 counties of Arizona and California.

Tumacácori National Historical Park is also featured in the National Park Service Places Reflecting America's Diverse Cultures: Explore their Stories in the National Park System Travel Itinerary and the American Latino Heritage Travel Itinerary.

Last updated: April 15, 2016