The Tlingit gathered in Shís’gi Noow and used delaying tactics to hamper the Russian advance. The Kiks.ádi---the most powerful of the Sitka clan houses---were certain that their clan allies, especially from Angoon and Kake, were on their way to lend aid, as they had in 1802. The Sitka Tlingit consulted their shamans when their allies did not arrive. The shamans reported that they had no vision of reinforcements arriving and that there was a “dark force” in the future.

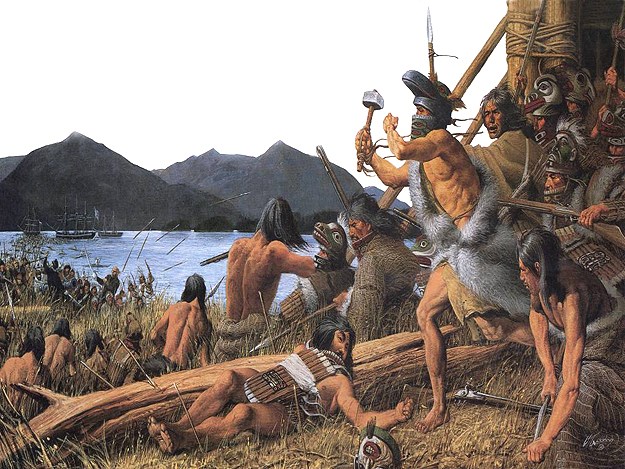

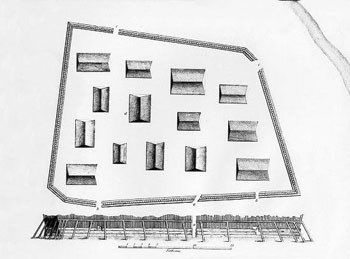

The Russians made landfall directly in front of the fort on October 1st, 1804. Baranov led the assault himself and charged up the bank at the mouth of Indian River. Nearly 400 Aleut and Alutiiq natives were the first to reach the fort walls, but the Tlingit waited until the Russians came into range. At once they fired into the Russian ranks. The Aleut and Alutiiq hunters broke ranks and ran for their baidarkas, pursued by Tlingit warriors sprinting from the gates of Shís'gi Noow. The Russians pressed the attack, but K'alyáan and an elite group of Tlingit warriors crushed the Russian's right flank. The Russian advance crumbled and Baranov himself was shot in the chest, dragged from the battlefield, and ferried back to the Neva. Cannon fire from the Neva was the only thing that stopped the destruction of the entire Russian landing party. The Tlingit had defeated the Russians again, but the battle wasn't over. Unfortunately for the Tlingit, their reserve gunpowder supply exploded as it was being paddled in a canoe to Shís'gi Noow immediately prior to the October 1st engagement. Without gunpowder, they were unlikely to repel another Russian attack. The Tlingit laid plans for tactical withdrawal. Over the next few days they engaged in diplomatic meetings with the Russians to buy themselves time. Once ready, the clans began what is now known as the Survival March. By the time the Russians made it to shore, the Tlingit had withdrawn to the east side of Chichagof Island to plan the next battle from another location. The Russians landed at the abandoned Noow Tlein, fortified it and renamed it Novoarkhangel'sk (New Archangel). The Kiks.ádi relocated to Chaatlk'aanoow, an abandoned fort that they quickly repurposed, reinforced, and stocked with food and weapons. From their fort overlooking the water, the Kiks.ádi could see any canoe or ship heading toward Sitka and take action.

Whenever canoes were spotted, the Kiks.ádi rowed out to meet them and to warn, "Stay away from Sheet'ká! The Kiks.ádi remain at war with the Anooshee [the Russians] and will not allow trading canoes to pass Chaatlk'aanoow. Sheet'ká still belongs to the Kiks.ádi."*** The blockade proved to be effective, and fewer and fewer boats tried to make their way to Sitka. Americans were eager to take advantage of the blockade. They quickly established Trader's Bay across from Chaatlk'aanoow, where Tlingit people from around Southeast Alaska could trade with the Americans instead of the Russians at Sitka. The Americans also sold firearms to the Tlingit, which effectively undermined Russian control of Sitka.

Lydia T. Black, Russians in Alaska, 1732 –1867 (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2004). Dauenhauer, Dauenhauer, and Black, eds., Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008). Sergei Kan, Memory Eternal: Tlingit Culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity Through Two Centuries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999). John Dusty Kidd, Over the Near Horizon: Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Russian America, (Sitka, Alaska: Sitka Historical Society, 2013). David J. Nordlander, For God and Tsar: A Brief History of Russian America, 1741 –1867 (Anchorage: Alaska Natural History Association, 1998). Ilya Vinkovetsky, Russian America: An Overseas Colony of a Continental Empire 1804 –1867 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Mary E. Wheeler, "Empires in Conflict and Cooperation: The 'Bostonians' and the Russian-American Company" Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 40, No. 4: 419-441. |

Last updated: April 26, 2016