National Park Service

National Park Service The Mine’s Beginnings

One day all that changed when a Baltimore man named John Detrick hiked along Quantico Creek. Near the confluence of the North and South Forks, he noticed something shiny in the water. It was pyrite, known commonly as “fool’s gold” and scientifically as Iron Sulfide. One of the great ironies of this area was that “fool’s gold” would prove more profitable than the real gold found in the Greenwood Gold Mine. The Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine began operations on a limited basis from 1889 to 1908, when the Cabin Branch Mining Company formed. In 1916, the American Agricultural Chemical Company bought the ride.

The large number of patents in the mid-nineteenth century and industrial growth after the Civil War made pyrite profitable. Sulfur was a necessary ingredient in products such as glass, soap, bleach, textiles, paper, dye, medicine, sugar, rubber, and fertilizer. When World War I broke out, the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine contributed to the production of gunpowder.

National Park Service Daily Work

National Park Service Despite any economic benefits, there was a human toll to the work. While the mine provided some additional income to local families, it was not enough to make a significant difference. Laborers returned to their farms after their long shifts to work the land. There were also numerous deaths and injuries. One worker was decapitated by an elevator. At least one man, Euriel Reid, died from poison gas and is buried in the park. Several others were injured, including an African American railroad engineer whose train derailed.

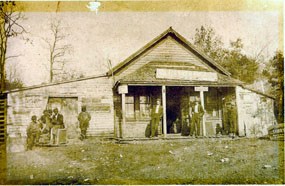

National Park Service There was also a company town, consisting of more than seventy buildings. There was a company store, machine shop, blacksmith, engine room and a small gauge railroad. When the railroad was not being used for mine operations, it took families, especially children, to the Potomac River to fish. Part of workers’ salaries came in the form of coupons for the company store. The town also included six dormitories for black workers and small houses for white employees and their families.

National Park Service The Mine’s Closing and Environmental EffectsAfter World War I, the price of pyrite dropped. Nationwide, in many industries, workers struck. While there is no evidence of union activity, workers at the Cabin Branch Mine struck in 1920. They demanded a 50 cent raise. The owner of the mine allegedly responded, “Before I will give you another penny, I will let the mine fill up with water and let the frogs jump in!” By this time, cheaper sources of sulfur were found overseas.

The mine closed in 1920, and most workers returned to their farms. A fortunate few found work in Dumfries and Quantico, but most remained on their small homesteads. The company left piles of pyrite tailings along the banks of Quantico Creek, and the concrete and wood buildings of the company town stood empty. While the mine’s closing certainly affected workers and their families, it affected the environment for generations.

National Park Service The largest reclamation project to date began in 1994. The pyrite tailings were buried under top soil and lime. Channels around these hotspots diverted rainwater, preventing acidic runoff from flowing into the creek. Measures were also taken to keep the creek’s bank in place. The mine shafts were capped with concrete. Since this reclamation, which as been somewhat successful, the National Park Service has planted Virginia pines.

National Park Service Aftermath

|

Last updated: December 10, 2022