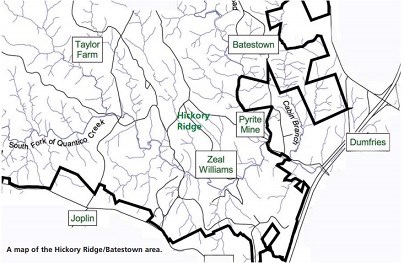

Courtesy of Louis Berger, Inc. "There is no community like this one anywhere else." In the early 1930s, acquisition of land by the federal government created a new chapter in the story of this land. Though this effectively ended a 400-year history of families, schools, stores, and industries that once inhabited the area, it left a unique opportunity to tell the stories of these places that are lost to time. Once inside today’s 15,000 acre Prince William Forest Park, local residents and travelers find a tranquil respite from the hustle and bustle. But beneath the forest canopy, the park holds a rich history that must be told—it is a story of enterprise, survival, and tolerance which has lessons for this and future generations. Learn more about African American history on lands that became part of the National Park Service. Batestown (1865-1935)Free African Americans were present in Prince William County as early as the mid-eighteenth century. After the Civil War, free former enslaved persons joined other African American families in a community which developed near the Cabin Branch Creek. Batestown, as it came to be known, was located on the eastern boundary of the park, along the road currently known as Batestown Road. Betsy Bates, considered the matriarch of the family, was born around 1795 and was the first of the Bates in the area of Cabin Branch creek. By end of the 19th century, Batestown counted 150 residents; by the beginning of 21st century, 75 residents called Batestown home. Descendants of the Bates family and Batestown community continue to reside in the area. Hickory RidgeThe community of Hickory Ridge developed west of the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine near Parking Lot D. It grew out of the property originally purchased in 1869 by Zeal Williams, the first African American property owner in the area. Over time, his land was divided among heirs, sold to relatives, and eventually came to be known as Hickory Ridge. Hickory Ridge was always a racially mixed community but its leaders were African American. Some of prominent families were the Williamses, the Kendalls, the Reids, and the Byrds.

NPS Photo Pyrite MineThe Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine operated from 1889 to 1920 and provided jobs to many of the men of Batestown and Hickory Ridge. Although both African American and European immigrants were employed there, implying that the Cabin Branch Mine may have been an integrated place of employment, maps of the mine area do show evidence of “colored quarters.” The mine was closed by a labor dispute in 1920, and the site remained severely polluted. A comprehensive environmental reclamation and restoration of the site was undertaken in 1995 to address the decades of lingering impacts from mine operations on the landscape and Quantico Creek. Amidon FarmDaniel Amidon was the first documented resident of the Hickory Ridge area. He was an immigrant from New York who set up a farm on land he bought in 1852. The Hickory Ridge community was located in and around the junction of Scenic Drive (then known as ridge Road) and Pyrite Mine Road. Clifton MillQuantico Creek has always been a valuable resource for the people who have inhabited the land of Prince William Forest Park. A mill stood on the creek as early as 1692 and at least four mills stood in the park at various times between 1780 and 1900. Clifton Mill is the only visible example of mill remains that have been found in the park. It is located just below Cabin Camp 4 on the North Fork Quantico Creek. The mill was in operation for 40 years. As described by an advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette in 1803, the mill was “an over-shot water wheel with a wheel of 20 feet 9 inches and four feet head, with two pairs of stones.” The mill house was 50 feet long, 27 feet wide, two stories high, with a small kiln for drying corn, together with a barn, stable, cow house, and lumber house, convenient to the mill. From 1813 to 1824, the Clifton Mill belonged to inventor and businessman James Deneale, a resident of Dumfries. The mill did not prove to be a profitable venture, however, and in 1818, Deneale advertised it for sale in the Alexandria Gazette. Little Union Baptist ChurchPrior to the founding of this church, the faithful of Batestown had to travel long distances on foot and by horse and wagon to attend church services. Mary Bates Thomas and her husband John Thomas, two former enslaved persons who became stalwart members of the black community, realized the need for a local church for the families who lived in the area. They donated land for the building of a church, and on September 9, 1901 they filed a deed at the Manassas courthouse, stating that the property was given for the exclusive use of the New School Baptist Church. The church was completed in 1903, under its present name, Little Union Baptist Church. Originally served by itinerant ministers, the church claims a rich history of devout Christians who took pride and comfort in serving their community. The church, now in its third sanctuary on Mine Road, continues its original mission of worship, fellowship and evangelism, crediting its existence to a persistent woman named Mary Bates Thomas. Cabin Branch SchoolEducation was highly valued among the black families of the Cabin Branch area, as evidenced by the numbers of children who often walked up to 14 miles to attend school. The Cabin Branch School, also known as Clarkson school, was located on today’s Mine Road and was established in 1889 to accommodate the local African American children. Florence's Store"The people would gather at this store nearly every evening ... and talk over what's going on and what they did during that day, and this is how the news got around from one farm to another," former resident. Poor House (1794-1927)With the enactment of Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1785, responsibility for the care and oversight of the poor was transferred from the Anglican church to county governments. In 1794, local elected officials, known as Overseers of the Poor established the Prince William County Poorhouse in the northwest corner of the park to house the county's neediest residents: the elderly, the infirm and those who had no family to care for them. This was a racially integrated facility, although white residents outnumbered African Americans. Records indicate that the Poorhouse was in operation until 1927, when a consolidated facility was opened in Manassas and Prince William county sold the property for $2,000. Odd Fellows Hall"They held meetings and helped the poor and different people around in the community...," former resident.

NPS Photo Reid Family CemeteryBy the 19th century, Virginians had abandoned the English custom of burying their dead in churchyards. Instead, they typically held funerals at home and buried family members on their own farms. Oftentimes, the family house would sit high on a ridge and the family graveyard would be placed farther down the ridge. In other instances, the graveyard would be on the next ridge over from the house. Evergreens and cedar trees, symbols of eternity, were commonly planted to designate the place as sacred. A survey conducted in 1995 documented over 40 family cemeteries within the boundaries of the park. |

Last updated: June 18, 2024