Last updated: March 22, 2021

Person

Mink Brigade

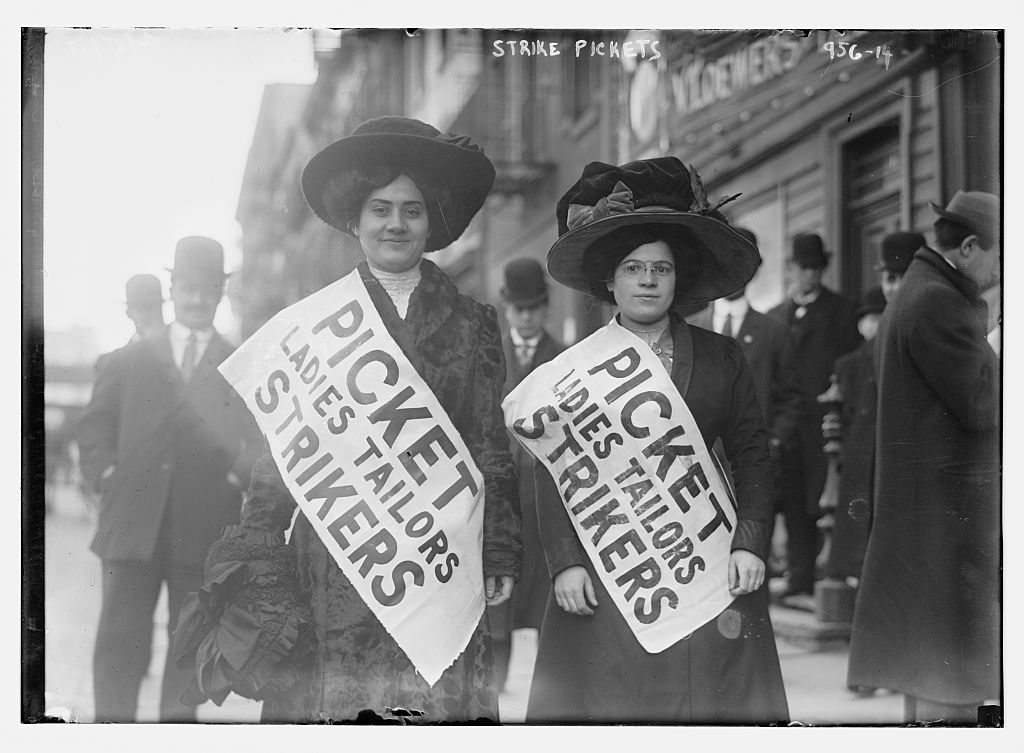

Courtesy Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/90706642

The “mink brigade” was a group of wealthy women who supported the labor movement in the early 1900s. Society women like Alva Belmont and Anne Morgan—who could afford to wear mink—walked picket lines alongside striking workers. Their social status helped protect the strikers from police abuse and attracted sympathy to their cause. As union leaders pointed out, much of the public was more shocked by the mistreatment of "respectable" women than by the conditions working-class women faced every day.

Have you ever worked on a project with someone whose life was very different from yours? How did you try to understand their point of view?

In 1909, thousands of garment workers in New York factories went out on strike. Most of these workers were young, immigrant women with roots in Southern and Eastern Europe. They risked arrest and lost wages to demand better hours,  safer conditions, and fairer pay. The strike was soon known as the “Uprising of 20,000.”

safer conditions, and fairer pay. The strike was soon known as the “Uprising of 20,000.”

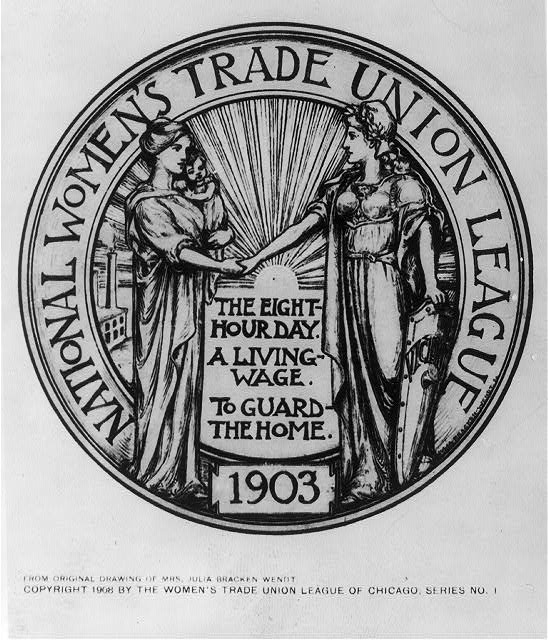

Leaders like Clara Lemlich, Rose Schneiderman, and Pauline Newman motivated the strikers. They picketed for three months on the wintry city streets. Through an organization called the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), they collaborated with wealthier women like suffragist Alva Belmont and reformer Mary Dreier.[1]

Philanthropists like Anne Morgan, Dorothy Whitney Straight, and Arabella Huntington funded the cause. Morgan was the daughter of financier J. P. Morgan, Whitney Straight belonged to the prominent Whitney family, and Arabella Huntington was at one point known as the richest woman in America.[2] They covered food and rent for picketing workers. They also bailed strikers out of jail. Anne Morgan told the New York Times:

“If we come to fully recognize these conditions, we can’t live our own lives without doing something to help them, bringing them at least the support of public opinion.”

Some of these women joined the pickets themselves. Their expensive clothes identified them as members of high society. They were later mockingly termed the "mink brigade," but their presence made a difference.  Police were reluctant to beat or mistreat strikers when "respectable" women were among them. When they arrested WTUL president Mary Dreier, a public outcry drew sympathy for the striking workers.

Police were reluctant to beat or mistreat strikers when "respectable" women were among them. When they arrested WTUL president Mary Dreier, a public outcry drew sympathy for the striking workers.

As union leader Rose Schneiderman wrote, the mink brigade "lent prestige and, more important, an aura of respectability to our demonstrations. This was most important for it helped to weaken the attempts of the unsympathetic to force the women back to work through prison sentences and physical violence."

The alliance between upper-class and working-class women was not without tension. Union women sometimes felt patronized by their wealthier allies. They argued that wealthy women could not understand what workers' lives were like. They also pointed out the unfairness of a society that was shocked at violence against wealthy women, but unmoved when the victims were workers.

In 1911, a devastating fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Greenwich Village made the stakes of the movement painfully clear.[3] The factory managers had locked the doors to the stairwells to keep workers from taking unauthorized breaks. As a result, scores of them were trapped.

Of the factory's five hundred employees, one hundred and forty-six died in the conflagration. Sixty-two of them died after falling or jumping from the building's windows, trying to escape the flames. Most of the victims were women and girls, some as young as fourteen years old.

Following the fire, Rose Schneiderman gave an impassioned speech to the WTUL. She argued that money and sympathy from wealthy supporters was not enough:

“I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting… you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers, and sisters by way of a charity gift. … I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.”

Schneiderman and her allies continued to work to build this movement, but they did not give up on cross-class collaboration. The WTUL worked on protective legislation for women as well as suffrage. In 1923, future First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt joined the WTUL. She and Schneiderman became close associates. [4] Members of the "mink brigade" influenced the labor legislation of the New Deal and beyond.

In 1923, future First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt joined the WTUL. She and Schneiderman became close associates. [4] Members of the "mink brigade" influenced the labor legislation of the New Deal and beyond.

Notes

[1] Alva Belmont, also a benefactor for the suffrage movement, and Alice Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party, are the namesakes of what is now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument in Washington, DC. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and designed a National Historic Landmark in 1974. It became a NPS unit in 2016.

[2] The Elms, a mansion built by the Whitney family in Newport, RI in 1901, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 10, 1971. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on June 19, 1996.

[3] The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory building, now known as the Brown Building, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 17, 1991.

[4] Schneiderman became a close friend and associate of Roosevelt and often spent time at Val-Kill, Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, NY. Val-Kill Cottage joined the NPS as Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site in 1977.

Bibliography

Johnson, Joan Marie. Funding Feminism: Monied Women, Philanthropy, and the Women’s Movement, 1870-1967. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

“Miss Morgan Aids Girl Waiststrikers,” New York Times, Dec. 14, 1909, pg. 1. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1909/12/14/101750159.html?pageNumber=1

O’Farrell, Brigid. She Was One of Us: Eleanor Roosevelt and the American Worker. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010.

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Schneiderman, Rose. All for One. New York: P.S. Eriksson, 1967.

Schneiderman, Rose. “We Have Found You Wanting.” Speech at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, NY, April 2, 1911. http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/primary/testimonials/ootss_RoseSchneiderman.html

Article by Ella Wagner, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.