Last updated: November 1, 2021

Person

Mary Amdur

Fair use

Dr. Mary Amdur was a public health researcher who is known as the “mother of air pollution toxicology.” She became interested in the subject after the Donora smog of 1948. Amdur studied how the interactions of particles and gases in smog affected the lungs of humans and animals. Her research influenced the development of air pollution standards in the United States.

Background

Mary Ochsenhirt Amdur was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on February 18, 1921. She earned her bachelor’s in chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh in 1943. Three years later, she earned her Ph.D. in biochemistry from Cornell University. Amdur became interested in air pollution after the Donora Smog of 1948, the worst air pollution disaster in U.S. history.

Donora Smog Disaster

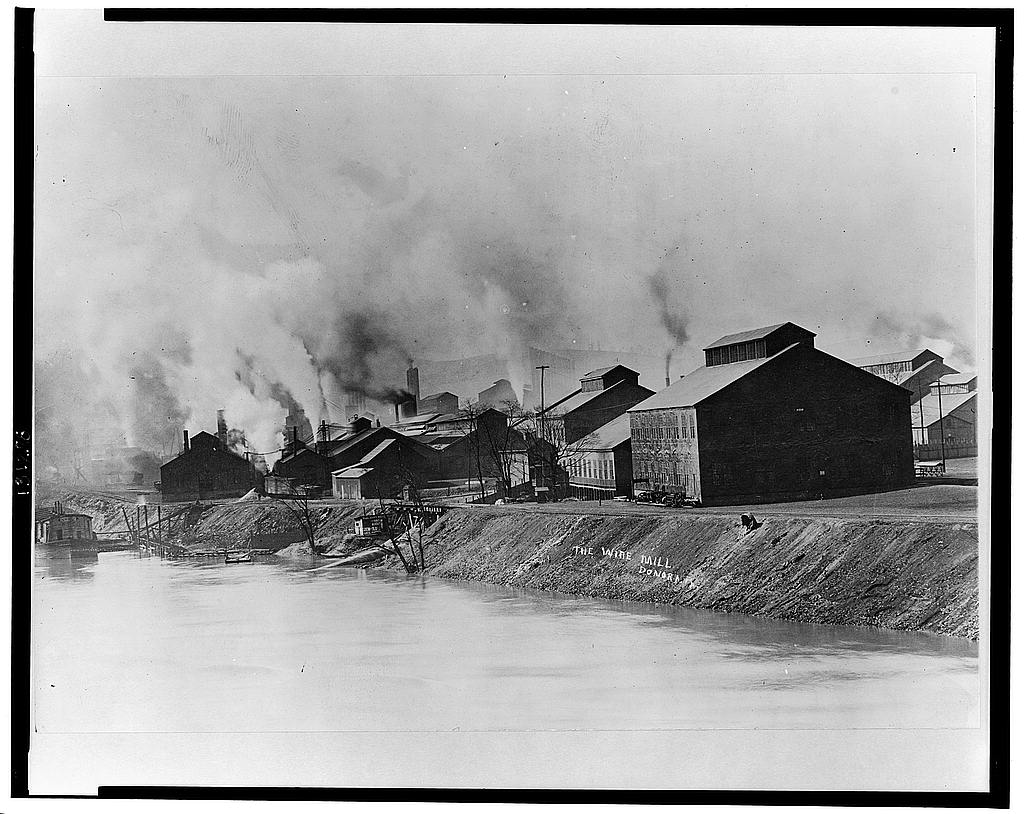

On October 26, an impenetrable smog enveloped the towns of Donora and Webster, Pennsylvania. The smog resulted from a change in atmospheric temperature. It trapped emissions from nearby zinc and steel plants beneath a layer of warm air.

Over the next few days, residents began to have trouble breathing. Some suffered from coughing, head and chest pain, and nausea. People's eyes stung. Some people's skin turned blue from lack of oxygen. Doctors advised people who already had heart or lung issues to evacuate. But low visibility on the roads made it impossible for even emergency vehicles to operate.

The arrival of rain on October 31 finally cleared the smog. By then, twenty people had died. Autopsies from three of the deaths revealed severe lung damage.

For years, Carnegie Steel, Zinc Works, and American Steel and Wire Company processing plants had released emissions downwind toward Donora and Webster.[1] But many residents worked at the processing plants. They were reluctant to criticize such important employers. A few residents sued these companies for damaging their health as early as 1918. Unfortunately, few laws held companies responsible.

After the Donora smog, the U.S. Public Health Service and the Pennsylvania Bureau of Industrial Hygiene launched studies. They determined that the smog had affected mor ethan forty percent of Donora's population. A high concentration of sulfur dioxide had caused the illnesses.

Aftermath of Donora

In 1949, Mary Amdur started working at the Harvard School of Public Health. She took on a project funded by the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO).

After the Donora smog, ASARCO knew it could be held responsible for health defects caused by its own emissions. The company wanted Amdur to show that sulfuric acid only had a minor role in the Donora smog. It hoped to avoid responsibility for damage caused by its main emission, sulfur dioxide. To ASARCO’s dismay, Amdur’s research suggested negative effects among people who inhaled sulfuric acid, sulfur dioxide, or both.

Lawyers and corporate executives from ASARCO and other smelter companies responded with hostility. In April 1954, an ASARCO representative attacked Amdur’s research at the American Industrial Hygiene Association meeting.

Lawyers and corporate executives from ASARCO and other smelter companies responded with hostility. In April 1954, an ASARCO representative attacked Amdur’s research at the American Industrial Hygiene Association meeting.

When the companies threatened to withdraw funding from the Harvard School of Public Health, Amdur’s boss caved to the political pressure. He withdrew her paper from publication. When Amdur returned from the conference, she discovered her project had been terminated.

Air Pollution Research

Over the course of her career, Amdur brought her research to Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and New York University (NYU). Despite the reputation and funding she gained for her work, Amdur remained untenured at all three institutions.

After the ASARCO controversy, Amdur got a new job within the Harvard School of Public Health. Although it was a lateral move, she could continue her research with the physiology department. Amdur developed a model to study how sulfur dioxide interacted with other particles in the respiratory tract in mammals. This physiological model became the basis of her research and professional reputation for over 40 years.

In 1977, Amdur left Harvard to collaborate with engineers at MIT’s Energy Laboratory. She studied pollutants produced from burning fossil fuels. But Amdur believed air pollution toxicology would remain neglected at MIT. In 1989, she moved her research to NYU’s Institute of Environmental Medicine. Although Amdur remained untenured, the job offered flexibility. She only went into work in Tuxedo Park, New York twice per week. This enabled her to care for her ailing husband in their home in Westwood, Massachusetts.

Legacy

After Amdur retired in 1996, she continued to write and consult at NYU. She edited manuscripts and worked to preserve the legacy of her career.

Amdur’s air pollution research was groundbreaking. Her work influenced amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1966 and the development of the Air Quality Act of 1967, which expanded federal authority to regulate air pollution.

When the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created in 1970, it established national standards to regulate air pollution. Amdur later served on the EPA’s Clean Air Act Scientific Advisory Committee. She also served on advisory committees for the National Institutes of Health and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Amdur won several professional awards. In 1997, she became the first woman to receive the Society of Toxicology’s Merit Award.

On February 16, 1998, Amdur died of a heart attack.

Notes

[1] The Cement City Historic District encompasses concrete housing that was built for employees of the American Steel and Wire Company. The district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1996.

Bibliography

Amdur, Mary O. “Health Effects of Air Pollutants: Sulfuric Acid, the Old and the New.” Environmental Health Perspectives 81 (1989): 109-113. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8981109.

Boston Globe. “Mary O. Amdur, 76: Toxicology professor, researcher.” Obituaries. February 23, 1998. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/73404486/obituary-for-mary-o-amdur-aged-76/.

Costa, Daniel and Terry Gordon. “Profiles in Toxicology: Mary O. Amdur.” Toxicological Sciences 56, no. 1 (July 2000): 5-7. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/56.1.5.

Davenport, S. J. and G. G. Morgis. Air Pollution: A Bibliography. Bulletin 537. Bureau of Mines. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1954. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bulletin/TiQjAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Jacobs, Elizabeth T., Jeffrey L. Burgess, and Mark B. Abbott. “The Donora Smog Revisited: 70 Years After the Event That Inspired the Clean Air Act.” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 52 (April 2018): 585-588. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304219.

Schrenk, H. H., Harry Heimann, George D. Clayton, W. M. Gafafer, and Harry Wexler. Air Pollution in Donora, PA: Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948: Preliminary Report. Public Health Bulletin no. 306. Washington, D.C.: Federal Security Agency, Public Health Service, Bureau of State Services, Division of Industrial Hygiene, 1949. Accessed October 21, 2021. http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/31320170R.

Snyder, Lynne Page. “Revisiting Donora, Pennsylvania’s 1948 Air Pollution Disaster.” Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region. Edited by Joel A. Tarr. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt6wrc59.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.