Last updated: January 12, 2026

Person

Maria W. Stewart

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Considered the first African American woman to speak in public on political, religious, and racial issues, Maria Stewart advocated for the abolition of slavery, for racial uplift and equality, and for women’s rights.

In 1879, Maria Stewart succinctly captured her early life by writing:

I was born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1803; was left an orphan at five years of age; was bound out in a clergyman's family; had the seeds of piety and virtue early sown in my mind, but was deprived of the advantages of education, though my soul thirsted for knowledge. Left them at fifteen years of age; attended Sabbath schools until I was twenty...[1]

At some point, she came to Boston and, in 1826, married James W. Stewart, a shipping agent and veteran of the War of 1812. The Stewarts joined the small but vibrant free Black community in Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood. They attended the African Baptist Church, located in the African Meeting House. David Walker, a radical abolitionist whose pamphlet Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World called for Black people to fight against enslavement and oppression, knew the couple and influenced Maria Stewart's thinking. When Walker and his wife moved out of their former home at what is now 81 Joy Street, the Stewarts moved in. Just three years after their marriage, James Stewart died. Though James left Maria ample money in his will, "the executors literally robbed and cheated her out of every cent," leaving her destitute, according to her friend Louise C. Hatton.[2]

Following the death of her husband, as well as the death of her friend and mentor David Walker, Stewart merged her deepening faith with public action in the growing abolition movement. In 1831, she delivered a manuscript to the offices of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison's new newspaper The Liberator. That summer, she published her essay, Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build. The success of the piece led to a short but significant public speaking career for Stewart. She gave four recorded public lectures between 1832 and 1833.[3]

Her speech in September 1832 at Franklin Hall is one of the first recorded instances of an American woman—of any race—speaking in public. Rarely did women give public addresses in the early 1800s, especially in front of a "promiscuous audience"—one that contained both men and women. By daring to do so, Stewart embodied the equality she called for in her speeches. She staked a claim for Black women as leaders of the resistance to oppression which she believed God demanded of them.

Stewart used Biblical language and imagery to condemn slavery and racism. She exhorted Black audiences, especially women, to pursue education and to demand political rights:

How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles? ... Possess the spirit of men, bold and enterprising, fearless and undaunted. Sue for your rights and privileges... You can but die, if you make the attempt; and we shall certainly die if you do not.[4]

In direct and powerful language, she fearlessly attacked racism, slavery, and colonization, the movement to send free African Americans to Africa and elsewhere:

The unfriendly whites first drove the native American from his much loved home. Then they stole our fathers from their peaceful and quiet dwellings, and brought them hither and made bond men and bond women of them and their little ones: they have obliged our brethren to labor, kept them in utter ignorance, nourished them in vice and raised them in degradation; and now that we have enriched their soil, and filled their coffers, they say that we are not capable of becoming like white men, and that we never can rise to respectability in this country. They would drive us to a strange land. But before I go, the bayonet shall piece me through. African rights and liberty is a subject that ought to fire the breast of every free man of color in these United States, and excite in his bosom a lively, deep, decided and heartfelt interest.[5]

Stewart’s speeches and writings garnered great attention as well as controversy, perhaps hastening her departure from Boston. In 1834, she moved to New York, where she joined a Black "Female Literary Society" and began teaching. She spent her later years in Baltimore and then in Washington, D.C. In Washington, she worked as Matron of the Freedmen’s Hospital.[6]

In 1878, a new law made Stewart eligible to collect a pension from her husband’s military service in the War of 1812. Her friend Louise C. Hatton helped Stewart gather documents, testimonies, and other evidence to obtain the pension.

According to Hatton, while gathering the needed information:

I found out a great many marvelous things that would have remained hidden until the end of time. I also found out, from all the old personal friends of Mrs. Stewart, that she was then, as now, a very devout Christian lady, a leader in all good movements and reforms, and had no equal as a lecturer or authoress in her day...[7]

Stewart used the pension money to publish a new edition of her speeches and writings in 1879. She asked her old friend William Lloyd Garrison to contribute some words to this new edition. He wrote:

Your whole adult life has been devoted to the noble task of educating and elevating your people, sympathizing with them in their affliction, and assisting them in their needs; and, though advanced in years, you are still animated with the spirit of your earlier life, and striving to do what in you lies to succor the outcast, reclaim the wanderer, and lift up the fallen...Cherishing the same respect for you that I had at the beginning, I remain your friend and well-wisher.[8]

Stewart died in the Freedmen's Hospital shortly after the publication of her book.

Her remains are interred in Woodlawn Cemetery.[9]

Footnotes

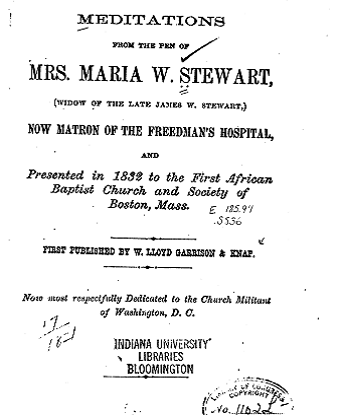

- Maria W. Stewart, "Preface," in Meditations From The Pen Of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, (Widow Of The Late James W. Stewart.) Now Matron Of The Freedman's Hospital, And Presented in 1832 to the First African Baptist Church and Society of Boston, Mass. (Washington: Enterprise Publishing Company, 1879), accessed February 12, 2025.

- Kathryn Grover and Janine V. DaSilva, "Historic Resource Study Boston African American National Historic Site," (2002), 42-44; Louis C. Hatton, "Biographical Sketch," in Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria Stewart.

- Michelle Levy, "Maria W. Stewart, Activist for ‘African rights and liberty,'" The Women’s Print History Project. July 24, 2020.

- Maria Stewart, “Prayer,” Meditations from the Pen of Maria W. Stewart.

- Maria W. Stewart, "An Address, Delivered in the African Masonic Hall, in Boston, Feb. 27, 1833," Liberator, May 4, 1833, 4.

- Alex Crummell, Meditations from the Pen of Maria W. Stewart. Note: Freedmen’s Hospital is now Howard University Hospital. The main quadrangle at Howard, the Yard, was added to the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark on January 3, 2001.

- Louise C. Hatton, "Biographical Sketch," in Meditations from the Pen of Maria W. Stewart.

- William Lloyd Garrison to Maria W. Stewart, April 4, 1879, in Meditations from the Pen of Maria W. Stewart.

- Stewart was buried in Graceland Cemetery, which closed in 1894; most bodies were disinterred and reburied at the new Woodlawn Cemetery. Woodlawn was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 20, 1966.