Last updated: April 6, 2022

Person

Madison Grant

Public domain.

Madison Grant was a key figure in the history of the National Park Service who left behind a troubling legacy. He supported environmental conservation and worked to protect plant and animal species like redwood trees and the American bison. While Grant is known for his contributions to wildlife protection, he is best remembered for his support of eugenics. His 1916 book The Passing of the Great Race spread racist ideas that Grant claimed were scientific. Policymakers used the ideas of Grant and those who agreed with him to restrict immigration and to control people’s ability to have children. Any history of the National Park Service is incomplete without an accounting of Madison Grant’s influence.

Conservation & National Park System

Madison Grant was born in New York in 1865 into wealth and privilege. He became a passionate sportsman, frequently taking fishing and hunting trips. In the late 1800s, many sportsmen—most of whom were wealthy, white men—worried about dwindling game numbers. They believed laws were necessary to curb over-hunting. Grant was an early member of the Boone and Crockett Club in New York and pushed for conservation laws alongside fellow hunters like Theodore Roosevelt. Their lobbying led to protections for the endangered bison of Oklahoma’s Wichita Mountains. This area became one of the country’s first national wildlife refuges.

Grant was also central to expanding the national park system. He and other conservationists advocated for the area now known as Glacier National Park in Montana to be protected. Elsewhere, Grant assisted with legally protecting the Everglades, Denali, and Olympic National Parks. He also led the Save the Redwoods League to protect California sequoia trees.

Grant and his colleagues were successful in advocating for many laws to protect lands across the US, from Alaska to the Adirondacks of New York. Animal populations began to bounce back. But conservationists often disregarded the human consequences of these projects. Conservation laws hurt many subsistence hunters who depended on hunting for food and income. In establishing national parks, state and federal governments assumed they were the rightful stewards of this land, regardless of the ancestral claims of Indigenous people.

Grant was successful because of his important connections and privilege as an affluent white male in American society. Politicians and social elites supported Grant’s environmental protection work. Grant fought for wealthy, white Americans to enjoy nature. He convinced his allies by using language that described a “pure” and “pristine” America.

This language of purity also appeared in debates about immigration and eugenics that raged in the early twentieth century. In Madison Grant’s case, these images were connected. He argued that both white Americans and “pure” nature needed to be protected from “invasive,” non-native species.

What is Eugenics?

Literally meaning “to be well born,” eugenics is the belief that a society should improve itself by controlling people’s reproduction. Eugenicists believed that some groups of people should be prevented from having children. Madison Grant was among those who invented elaborate systems for classifying people based on their real or perceived disabilities. Further, Grant and other eugenicists argued that certain racial groups were superior to others. Today, we call these theories “scientific racism.” They use the language of science but have no basis in evidence.

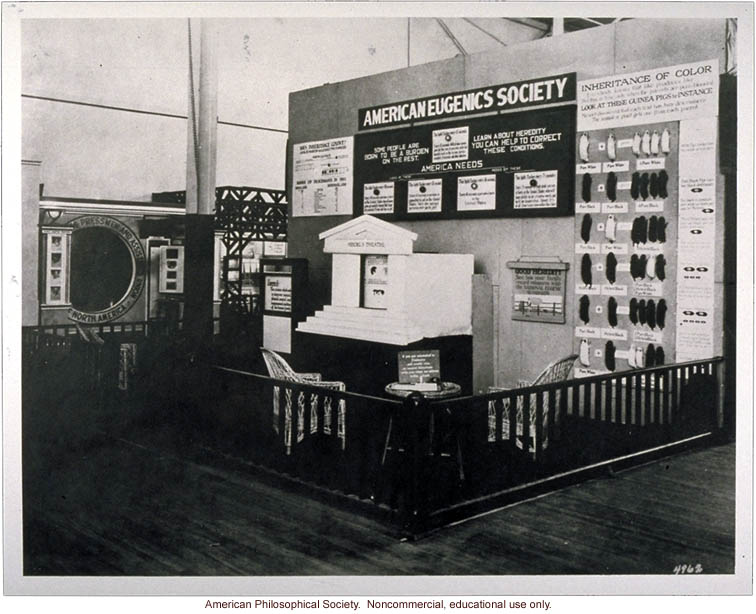

An exhibit of the American Eugenics Society at the Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia, 1926. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

These ideas emerged out of Charles Darwin’s 19th-century findings on evolution. Social theorists, like Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton, twisted these theories of evolution and applied them to human beings. Known as “Social Darwinism,” this concept asserted that certain groups were more “fit” to survive than others. People like Galton—and later, Madison Grant—used this concept to justify imperialism and colonization. Galton expanded on the idea of Social Darwinism, coining the term “eugenics” in the 1880s.

Social Darwinism, scientific racism, and eugenics were widespread in the early 1900s. These ideas caused untold harm to vulnerable people. Eugenics policies targeted people with disabilities, those who were incarcerated, people of color, and poor communities. Many well-educated and powerful people and institutions supported them. But other prominent voices criticized these ideas and policies. The anthropologist Franz Boas, for example, spoke out against eugenics. He worked to show what scientists now accept: that race is a social construction, not a biological reality.

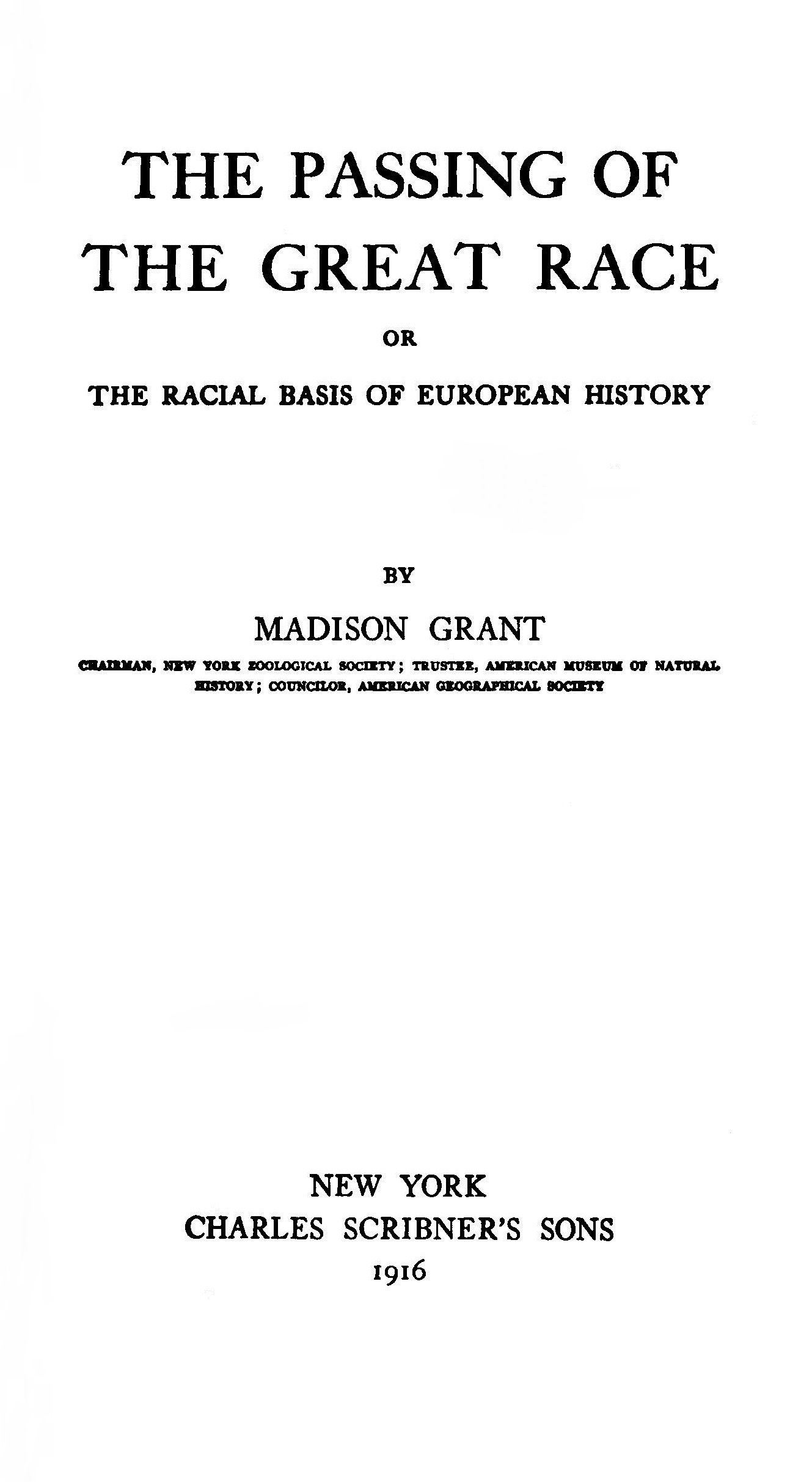

The Passing of the Great Race

Madison Grant’s influential book The Passing of the Great Race (1916) advanced his racist ideas. Grant claimed that people from Northern Europe were at the top of a natu ral racial hierarchy. He called white people from Nothern and Western Europe "Nordics" and asserted that they had evolved in a harsh climate that had made them physically and intellectually superior. Although Grant used scientific language, his theories were not based on evidence.

ral racial hierarchy. He called white people from Nothern and Western Europe "Nordics" and asserted that they had evolved in a harsh climate that had made them physically and intellectually superior. Although Grant used scientific language, his theories were not based on evidence.

Grant alleged that this supposed "Nordic race" was in danger of going extinct. He claimed, without evidence, that immigration and racial intermarriage caused crime and political corruption. According to Grant's racist hierarchy, any mixing between "Nordics" and the other groups he saw as inferior could not be tolerated. He believed it would doom the United States.

Eugenics and Immigration Restriction

To solve this imagined "problem," Grant advocated for eugenics policies and immigration restriction. He supported forced sterilization, the surgical process of removing a person’s capacity to reproduce. He first focused on people with disabilities and those who had committed crimes. He suggested that “worthless race types” should also be sterilized. In The Passing of the Great Race, he wrote:

"A rigid system of selection through the elimination of those who are weak or unfit—in other words social failures—would solve the whole question in one hundred years, as well as enable us to get rid of the undesirables who crowd our jails, hospitals, and insane asylums. The individual himself can be nourished, educated and protected by the community during his lifetime, but the state through sterilization must see to it that his line stops with him."

In the United States, state governments passed eugenics laws that resulted in thousands of people being permanently placed in institutions. These laws also authorized the sterilization of tens of thousands of people. Many of them were poor people of color.

Grant also advocated for immigration restrictions. He was vice president of the Immigration Restriction League and lobbied for the Immigration Act of 1924, which sharply reduced the number of immigrants allowed into the country and set quotas based on national origin. These quotas had their roots in wrongheaded scientific racism, including statistics provided by Grant.

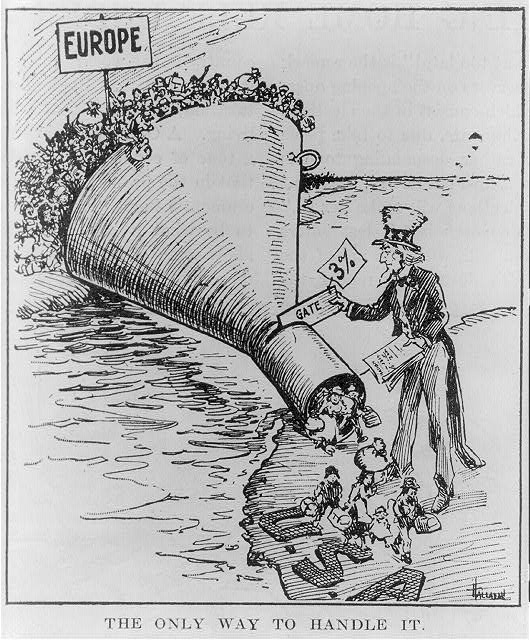

This 1921 cartoon advocates for an immigration quota system, depicting a funnel with the large end labeled "Europe" and the small end opening into "U.S.A." and labeled "3%." Courtesy Library of Congress.

Madison Grant was not alone in his beliefs about eugenics and hierarchy of races. He shared these ideas with other people who supported conservation and other social reforms. President Theodore Roosevelt, for example, supported sterilization of incarcerated individuals and people with cognitive disabilities. Margaret Sanger, an advocate of birth control, expressed similar views about Black Americans and people she deemed “defective.” While we often celebrate these Americans for their contributions to social progress, we must also remember their troubling legacies.

Death and Legacy

Grant never married and had no children. He died at the age of 71 from kidney disease. In his will, he left thousands of dollars to the New York Zoological Society, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Boone and Crockett Club. While his work as a eugenicist had been popular in the 1920s, it fell out of favor by the 1950s. His ideas became further discredited when it became public that Adolf Hitler and the Nazis found inspiration in Grant’s work, as historian Jonathan Spiro writes. In 2021, California State Parks removed a marker honoring Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park.

Bibliography

Spiro, Jonathan. Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Press, 2009.

Jacoby, Karl. Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001.

Spence, Mark David. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Taylor, Dorceta. The Rise of American Conservation: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Minna Stern, Alexandra. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005.

Mittlefehldt, Sarah. Tangled Roots: The Appalachian Trail and American Environmental Politics. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2013.

Catte, Elizabeth. Pure America: Eugenics and the Making of Modern Virginia. Cleveland, OH: Belt Publishing, 2021.

Gregg, Sara. Managing the Mountains: Land Use Planning, the New Deal, and the Creation of a Federal Landscape in Appalachia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Ordover, Nancy. American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

The Margaret Sanger Papers Project. New York University. Accessed 12 December 2021. https://sanger.hosting.nyu.edu/aboutms/msbio/.

This article was researched and written by Ella Wagner, fellow in the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, and Perri Meldon, fellow in the NPS Park History Program. Expert review was provided by Dr. Alexandra Minna Stern, Professor of History, American Culture and Women's and Gender Studies at the University of Michigan and the author of Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America.