Last updated: October 25, 2023

Person

Jun Fujita

Courtesy of the Graham and Pamela Lee Collection

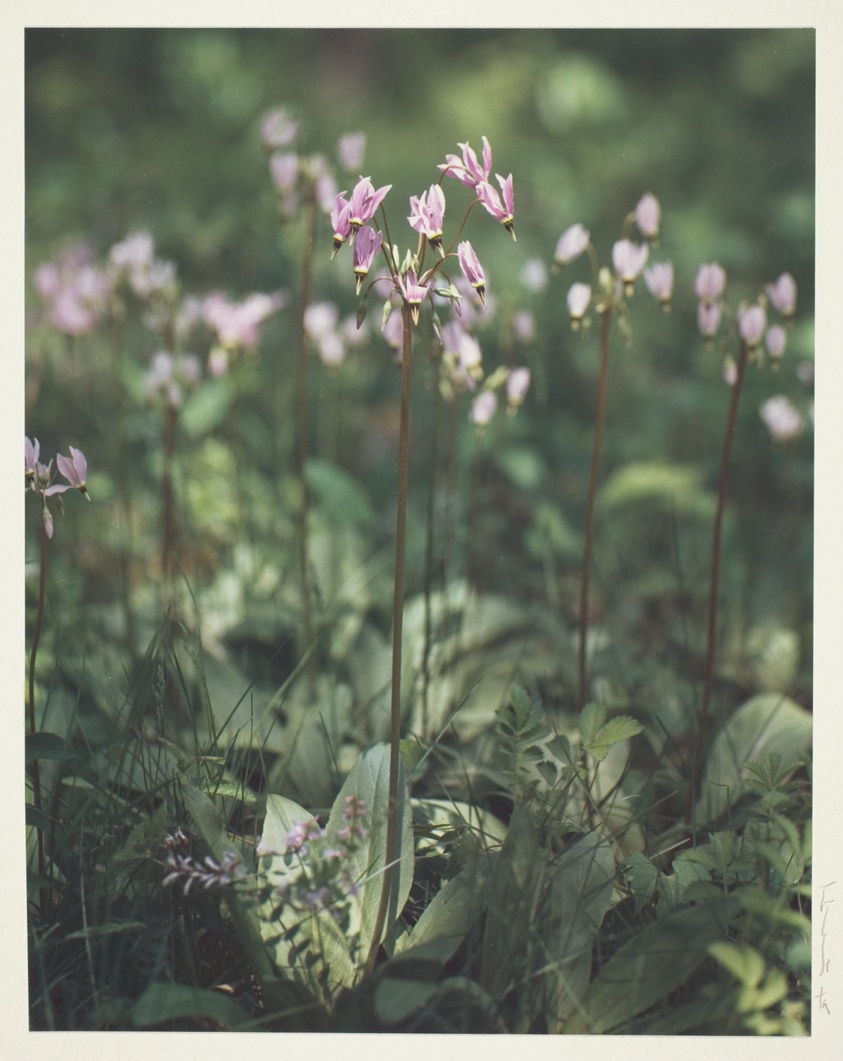

"Whether these flowers are rare or common they all have delicate languages and create vivid moods. I try to recreate these moods in my photographs." - Jun Fujita

Considered to be the first Japanese-American photojournalist, Junnosuke "Jun" Fujita is one of the earliest Japanese-Americans to have achieved prominence in the Midwest. He was an eminent photographer in the region— working in news, commercial, and artistic photography. He also had noteworthy success as a published poet, and is considered one of the first poets to compose tanka in English. Tanka means "short song," and is a form of waka, Japanese song or verse.

Around 1928, Fujita built a cabin on a wooded island in today's Voyageurs National Park. He used it for recreation and as a base for commercial photography until about 1941. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996. It is likely that the rugged setting of the cabin provided inspiration for Fujita's artistic work, which was dominated by portrayals of flowers, forests, and landscapes. The remote location of the cabin probably also provided an atmosphere conducive to reflection.

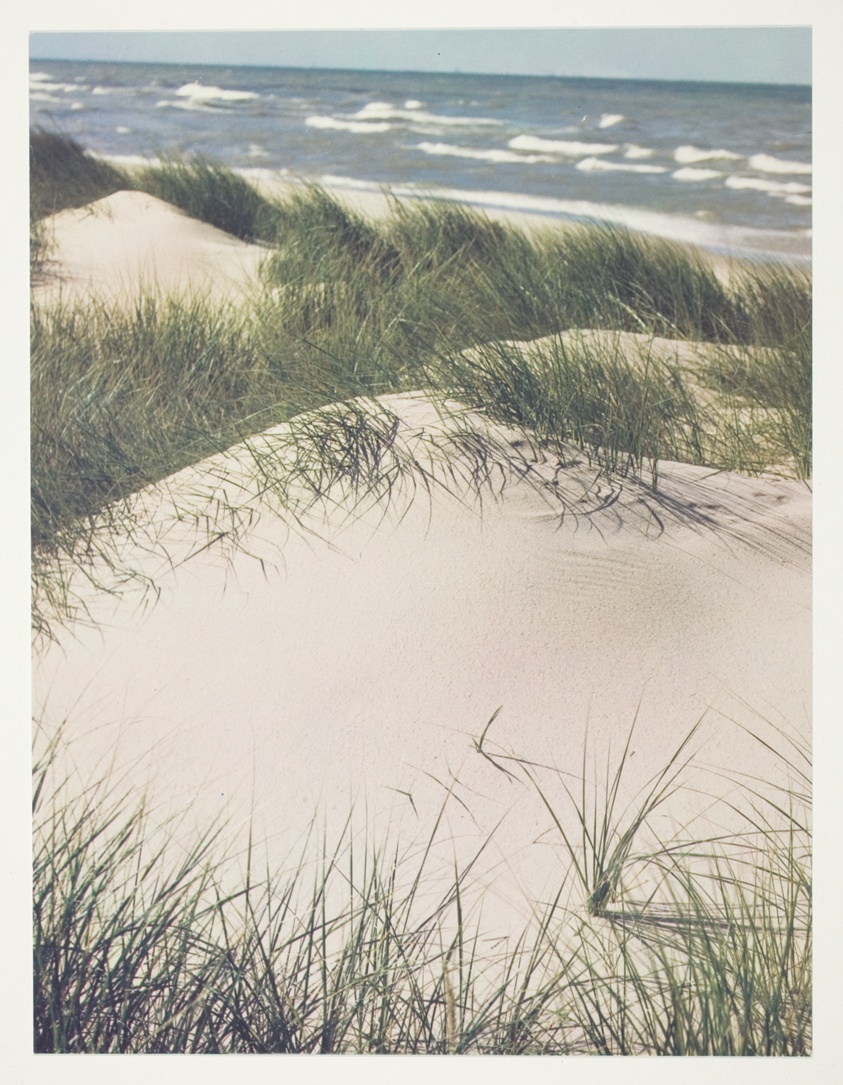

Around 1934, Fujita had a second cabin built; this time it was in the forested dunes of Indiana, similarly drawn to the area's seclusion as well as its wealth of inspiration. He used this cabin until his death in 1963. Although his cabin in Indiana no longer stands, the property is a part of today's Indiana Dunes National Park. Even meditative solitude and rugged recreation required unusual measures for a Japanese-American in Fujita's era experiencing xenophobia and legal discrimination against Asians.

"Spring;" Photograph by Jun Fujita; Art Institute Chicago Collection

Fujita was born in Hiroshima, Japan on December 18, 1888 and immigrated to Canada in 1906 at age 17, later finding his way to the United States. Fujita went to Canada on a commission to photograph Canadian lumbering for a Japanese publication where his uncle was an editor.

Fujita likely came to Chicago in 1909. According to his family in Japan, he only knew limited English when he arrived in Chicago. He brought with him netsuke, or carved, minature figurines that he would sell when he needed to make some quick cash. Japanese immigration to the United States was restricted in 1908, but a working photographer could have entered the U.S. legally until Japanese immigration was completely banned in 1924. Fujita was working in Chicago for the Evening Post by 1915.

After graduating from Wendell Phillips High School, Fujita attended night classes at the Armour Institute to become an electrical engineer. On the side, he took photography gigs and acted in silent films produced by Essanay Studios, an early motion picture studio in Chicago. (This studio used the Indiana Dunes landscape for far-away desert settings in films such as The Fall of Montezuma, 1911 and The Plum Tree, 1914.) Fujita had a lead role as the hero’s valet in the 1915 thriller Otherwise Bill Harrison, produced the same year that Essanay released Charlie Chaplin’s The Tramp. Fujita could not be found in Illinois in the 1910 census, but neither the census indexing nor the enumeration itself is completely reliable for this period; in fact, he was also not found in the census of 1920, when he certainly was living in Chicago. At this time, Jun was not seen as an immigrant, but as an "alien;" by law, Japanese individuals could not become citizens.

Despite this, Jun was known to "stand tall even though he was a short man," according to his great-nephew Graham Lee. He was a well-dressed, very confident young man that people wanted to get to know. Obituaries state that Fujita studied mathematics and physics at the Armour Institute in Chicago (today's Illinois Institute of Technology.) Fujita worked for the Evening Post until at least 1929, and probably a few years longer. His colleagues nicknamed him “Togo,” and few contempoary accounts written about him could resist dabbling in stereotypes. As early as 1915, agents from the Department of Justice trailed him after he took photographs near an army post. “The Jap came out at 11:00 a.m. and took two pictures of an automobile,” one dispatch read. The investigation never came to anything. Few of the Post's photos were attributed to particular photographers in Fujita's time, but photos by Fujita related to the sinking of the USS Eastland in the Chicago River in 1915 and the 1929 Saint Valentine's Day massacre have been located.

The Eastland Disaster in 1915 was Jun's first major assignment for The Chicago Evening Post. He was one of the first photojournalists on the scene, capturing the chaotic event. The USS Eastland was to leave Chicago and head for the Indiana Dunes to picnic in Michigan City, Indiana for a Western Electric company outing. The ship was at capacity (2,572 passengers) when the weight on the deck was so great that the whole passenger ship flipped upside down. This trapped and drowned 844 individuals- still the greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes.

USS Eastland Disaster: A horrified fireman cradling a dead child, which ran on the front page of the Post — shocked the nation. Photograph by Jun Fujita, 1915; Chicago History Museum, ICHi-030783

Another series of famous photographs by Jun include his shots of the Chicago Race Riots of 1919- one of which captured a stoning, considered one of the first images of a murder in real time.

Jun Fujita photographed the Illinois Army National Guard questioning a Black man during the racial violence that broke out in Chicago in 1919. Photograph by Jun Fujita; Chicago History Museum, ICHi-065477

In 1924, he covered the circus-like trial of teen-murders Leopold and Loeb. In addition to capturing dramatic, historic events of early 20th century Chicago, Jun also photographed prominent celebreties. He took portraits of Albert Einstein, Carl Sandburg, Frank Lloyd Wright, Theodore Roosevelt, and Al Capone. According to family lore, Al Capone is said to have appreciated how Jun could handle a knife, and even offered him a job (Fujita declined.)

After this fifteen-year career in news photography, Fujita turned to commercial and artistic work. In the 1930s, he established a private photography studio in Chicago, which he ran until his death in 1963. He was very successful in his commercial photography, doing work for the manufacturers of Johnson motors, and for Stark Nurseries, Sears Roebuck, and the federal government. His friends remember that he photographed the Hoover Dam before the outbreak of World War II, because of a standing joke among them about the potential consequences if he had been seen there with a camera during the war. The settings for some of the photography Fujita completed for Johnson Motors were around his cabin on Rainy Lake in today's Voyageurs National Park.

In addition to his commercial and news photography, Fujita produced artistic work in several different media. In all of these media, his favorite subjects were flowers and landscapes. He made this observation in a photoessay in Allstate Insurance's magazine Home and Highway in 1957:

We had been scouting around different parts of the country for many years-a busman's holiday; I would be looking for wild flowers to photograph. Whether these flowers are rare or common they all have delicate languages and create vivid moods. I try to recreate these moods in my photographs.

"Shooting stars;" Photograph by Jun Fujita; Art Institute Chicago Collection

The Art Institute of Chicago has a collection of Fujita's color photos of flowers and nature scenes. Some of these were done with very early color equipment, but the color is remarkably natural and the lighting very dramatic. Fujita wrote poetry in English using a minimalistic Japanese form called tanka. A friend of Fujita's who is an amateur poet remembers his writing haiku also. Many of his tanka were published in the 1920's in Poetry Magazine as well as other periodicals. Poetry is one of the country's most prestigious literary serials, and during Fujita's era it also published the works of such major figures as T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Robert Frost, and carried a regular column of criticism by Ezra Pound. Fujita also published several reviews of Japanese-American poetry in the same venue. A 1923 collection of Fujita's tanka was privately published and received a favorable review in Poetry. Fujita's poetry was highly unusual in that it applied the rules of Japanese poetic genres to poetry written in English well before the vogue of English haiku. Perhaps this is why he named his collection Tanka: Poems in Exile, implying that the poems themselves were in exile.

Here is an example of one of his poems, entitled "Morning Woods":

A static mood, in the morning woods,

Wet and clear —

In a majestic pattern, leaves are spellbound

By a fawn, ears perked.

Photograph by Jun Fujita; Art Institute Chicago Collection

Fujita had a long-term relationship with Florence Carr, a Euro-American woman who was about six years younger than he. Carr was a secretary and later a social worker, and she was a graduate of the University of Chicago. The two met at a meeting for the Chicago Poetry Society and became an immediate item. She and Fujita lived together from the early or mid 1920s until his death. It was illegal for mixed race couples to marry when they began to see each other, and did not marry until 1940.

In the early 1930s, Fujita and Carr lived in a bohemia known as the 57th Street Artists Colony in one of the old Columbian Exposition buildings, at 5644 Harper Street. When Fujita established his studio, they moved into an apartment above the business. Jun and Florence entertained dinner parties, where Jun was known to do the cooking. They were friends with news people, authors, university scientists, artists, and thinkers. Jun loved classical music and attending the Chicago Symphony. He was good friends with Carl Sandburg and had exchanged inscribed books. Jun seemed to know everyone; he even had inscribed one of his poetry books for Jean Harlow.

Fujita and Carr had another vacation cabin in present-day Indiana Dunes National Park, located on six acres they bought in 1934, near the houses of artist friends such as Vinol "Vin" and Hazel Hannell. Fujita became a part of the growing community of artists known as the Furnessville Artists Colony- drawn to the regions vast and unspoiled resources.

"the Kite," Fujita and Carr's Indiana cabin. Graham and Pamela Lee collection

The cabin at the Indiana Dunes was known as "the Kite" because of its diamond shape. Jun had some assistance from an architect friend in Chicago, but had made the general layout himself. Fujita and Carr hosted Carl Sandburg in the cabin as well as Pearl S. Buck. Neither Jun nor Florence had drivers licenses; so they often traveled to the Indiana Dunes by train.

Although Carr was the owner of the Minnesota property, local informants do not remember her. Fujita, the only Japanese person ever seen in the area at that time, is well remembered, but informants say he used the cabin alone. Similarly, the Indiana Dunes property deed listed Carr's name first, although Fujita was also listed.

Friends say Carr owned their property in her name because of fear that it could be confiscated from Fujita under state laws restricting land ownership by aliens, and particularly by Asian aliens. The provisions of these laws varied over time and between the three states where Fujita and Carr had property. Minnesota's legislature passed a law in 1945 that limited ownership of land over 90,000 square feet (slightly over 2 acres) by aliens who had not declared intent to become US citizens, although the law contained several significant exceptions and grandfathered in already-existing holdings. Asian aliens could not become U.S. citizens at this time, except under very extraordinary circumstances, so the discriminatory effect of this law fell most heavily on them. Illinois allowed aliens to hold land for up to six years. Although Indiana was a notoriously unfriendly place for ethnic minorities in this period, its state government allowed aliens who had not declared intention to become citizens to own holdings of not more than 320 acres.

Dunes Graveyard; Photograph by Jun Fujita; Graham and Pamela Lee Collection

Fujita and Carr were married in 1940. Friends say that Fujita and Carr married to protect their property from confiscation related to his Japanese citizenship. However, concern for their property should have discouraged them from marrying. Although the Cable Act of 1922, which nullified the citizenship of American citizens who married Asian immigrants, had been overturned, a revival of some form of this policy must have seemed possible in the anti-Japanese atmosphere of the war years. The Cable Act's primary purpose was to prevent men who were Asian immigrants from avoiding state-imposed property holding restrictions by marrying the U.S.-born daughters of other Asian immigrants, but the added complication of a racially mixed marriage might well have provoked extra vigilance on the part of enforcing authorities. In the event of a revival of some form of this policy, marriage would jeopardize Carr's property without protecting any held by Fujita in his own name. In 1940, Congress repealed the Expatriation Act of 1907 by the Nationality Act of 1940. Before it's repeal, a U.S. citizen would lose their citizenship if they married a non-citizen. Obviously, loss of citizenship could also cause various other problems for Carr.

Fujita was granted U.S. citizenship by a private Congressional bill in 1954. He was diagnosed with brain cancer in 1961, and died two years later on July 12, 1963 with Florence at his side. Florence donated much of his work to the Chicago Historical Society, today's Chicago History Museum. She also scattered his ashes at their Indiana Dunes cabin. Carr died in New York City a few years later.

The Poetry Foundation writes:

"Jun had lived a charmed American life full of adventure, travel, rewarding work, and glamorous and brilliant friends. But that bounty was hard won: over the years, he was followed by government agents, denied the right to buy property, declared an “enemy” by his adopted country, and condescended to even by those who admired him. Fujita and Carr never had children; according to Lee’s account, they feared life would be too hard for a multiracial child. Perhaps those insults and losses explain something about the persistently melancholic tone of his poetry, despite the exuberance of his life."

Across the frozen marsh

The last bird has flown;

Save a few reeds

Nothing moves.

Fujita's success as a photographer working for a mainstream newspaper and for major commercial corporations was extremely unusual among Japanese-Americans in his time, and especially among the Japanese-born population. The majority of Japanese immigrants arrived in the United States as farm laborers. Most of those who escaped agricultural wage labor did so by becoming sharecroppers or, with luck, independent small farmers. Even the considerable number of second-generation Japanese-Americans who experienced upward social mobility consisted mainly of professionals serving segregated Japanese-American communities.

Fujita was also one of the earliest Japanese residents of the American Midwest; as late as 1940, less than 5% of the 285,115 Japanese-Americans lived outside of Hawaii and the West Coast states. An lowan who remembered Fujita well from her summer visits to Rainy Lake pointed out that, "I suppose he was the first Japanese person I ever knew—and probably my parents [had also never previously met a Japanese person]."

Fujita established his vacation cabin at a time when a growing number of people were coming to the rugged Voyageurs area to enjoy outdoor recreation in a wilderness setting.

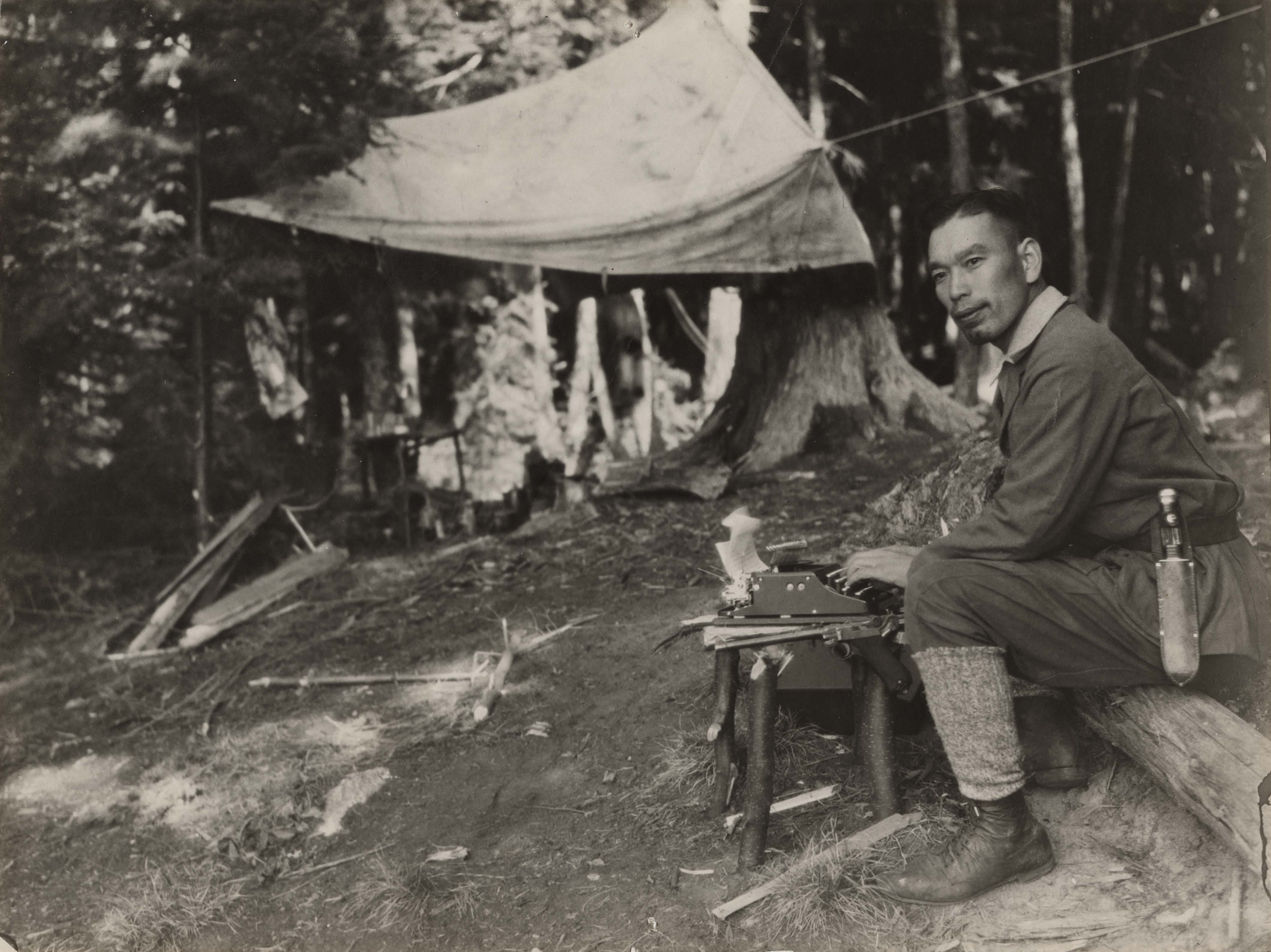

Undated photograph of Jun Fujita seated at a typewriter in a forested camp; Graham and Pamela Lee Collection.

Fujita clearly sought and found solitude on the island. In addition to the remoteness of the border lakes area in Fujita's time, the island is 30 miles from Ranier, the nearest town. Despite Fujita's isolation on the island, however, several long-time area residents were able to share their memories of Fujita's activities in the area. These informants say Fujita used the cabin primarily for recreational purposes but also for commercial photography. It is not known whether Fujita produced any of his artistic work at the cabin, but the rugged surroundings certainly suggest the subject matter of his poetry, artistic photos, and paintings. Fujita's quest for solitude was complicated by discrimination that led him to keep the property in Carr's name and prevented him from using the island after 1941.

A longtime seasonal visitor to the lake who visited Fujita's island a number of times during the 1930s reported that Fujita spent a great deal of time reading and meditating on the island. She commented that he "loved the silence, the quiet of the island...The rocks, the lake, the sound of the water, was in his soul." Although many people stopped by the island, "nobody stayed a long time" because no one wished to intrude on Fujita's solitude.

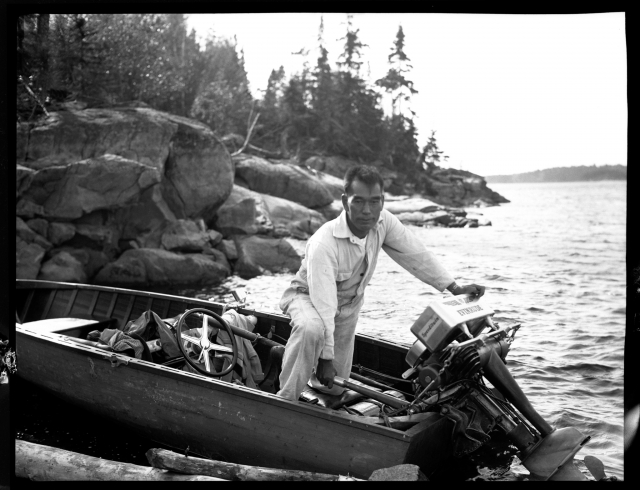

Jun Fujita boating on Rainy Lake. Photograph by Wayne Carr, ca. 1931; Graham and Pamela Lee Collection.

A more visible recreational activity Fujita pursued on Rainy Lake was his use of racing boats at a time when powerboats of any kind were still unusual in the area. Fujita also fished on Rainy Lake. The great majority of visitors to the lake do some fishing there, but Fujita was unusual in that he used the catch to prepare Japanese raw fish dishes at the cabin.

Longtime residents say Fujita also used the cabin as a base for his commercial photography for the manufacturers of Johnson boat motors, in which he photographed local people, boats, and Johnson motors. Since many Rainy Lake people remember Fujita's photography for Johnson, it is likely that it was relatively extensive. His photographs also played a role in the conservation of the natural beauty of the Rainy Lake area after the construction of dams was proposed. Boundary Waters conservationist Ernest Oberhauser used Jun's photographs.

Fujita supplied this image, and others, of Rainy Lake in support of the successful campaign to protect the watershed from a series of proposed dams. Photograph by Jun Fujita, 1931; Graham and Pamela Lee Collection

The constraints put upon Japanese-Americans during Fujita's era affected both the manner of his acquiring the cabin, as discussed above, and the time of his abandoning it. Fujita used the island from about the time of Carr's purchase in 1928 until shortly before the outbreak of World War II.

He barely avoided the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II. His commercial photography business had its assets frozen at the bank and his cameras were confiscated. According to his great-nephew Graham Lee, Fujita was able to pull in favors from the newspapers and his important friends in Chicago, most notably his former boss Michael Straus, editor of the Chicago Evening Post. He wrote to Mr. Staus, who was now a high-ranking official in the Department of the Interior:

“I feel all this so unreal, almost like a bad dream... My future is utterly unpredictable.”

Even as Japanese Americans on the West Coast were being held in internment camps by the federal government, he vowed to do anything he could to help the American war effort and sent documents and letters asserting his loyalty to his adopted homeland. “I left Japan in 1906, disliking her civil and social ideology,” he wrote.

“Today, it is very difficult for me to think in terms of myself as an enemy alien; I cannot feel that I am one.”

Eventually Fujita was allowed to reopen his business and carry on with life. He never returned to the Minnesota cabin after the beginning of the war, vacationing instead at the Indiana Dunes cabin, which is little more than an hour's travel from Chicago.

Friends of Fujita's and Rainy Lake informants assume that Fujita did not wish to travel the long distance to northern Minnesota during the war era because of the prevalence of anti-Japanese hostility. One informant reports it was rumored that Fujita was threatened by a local person at Rainy Lake at this time. It is indicative of the conspicuousness of Fujita's background that the island was popularly known as "Jap Island."

Fujita's Cabin at Voyageur's National Park

Photograph courtesy of Voyageurs Conservancy

The Fujita cabin is a modest, one-story cabin located on a small, remote island near the Canadian border on Rainy Lake in Voyageurs National Park in northeastern Minnesota. The simply constructed cabin presents an impression of deliberate rusticity and deference to the natural landscape. Chicago photographer and poet Jun Fujita is believed to have commissioned or performed the initial construction of the cabin soon after 1928, and to have made two additions before 1941.

Constructed on the eastern tip of a four-acre island, the cabin is located approximately 30 miles east of Ranier, the closest permanent settlement. The island scenery is dramatic, characterized by immense crevice-riddled boulders, rocky shorelines, and steep bluffs rising above the lake. The cabin has the appearance of requiring no modifications to the landscape and is thoughtfully integrated into the wilderness setting. Pine trees tower above the cabin on the north, east, and west sides. Tucked against a massive glacial erratic to the south, the cabin also takes advantage of a gentle rock ledge that provides easy access to the lake on the east.

The high degree of historical integrity and good physical condition that the Fujita cabin exhibits is distinctive for the area. The cabin is in its original location, where the setting and feeling have changed little since Fujita's time. The property maintains a high degree of integrity of design, materials, and workmanship. The harsh local climate has caused minimal deterioration to the cabin beyond the usual settling inherent to log construction.

The property exhibits qualities influenced by Japanese tradition-qualities imported by a teenage Fujita arriving in North America from a country that had experienced minimal exposure to Western ideas. As a Japanese immigrant, Fujita faced prejudices directed against all Asians after World War I. He had to make extraordinary efforts to acquire recreational property in the northwoods and was compelled to abandon the cabin with the beginning of World War II and renewed anti-Japanese hostilities. This civil rights factor underscores the significance of this particular recreational cabin and contributes to our understanding of discrimination against immigrants and Asians.

Florence Carr, friend and eventually Fujita's wife, bought the island for Fujita's use in 1928. The cabin was probably constructed shortly after Carr bought the property.

An exterior view of Jun Fujita’s cabin, undated. Graham and Pamela Lee Collection.

The original 13x16 frame cabin is covered with drop siding, initially painted a mustard yellow color and nailed directly to the pole studs. Multi-light casement windows are found throughout the cabin. The front door, which faces north, is flanked by vertical, 6-light casement windows which reach nearly from floor to ceiling. A large, rustic chimney built of native rubble is centered on the west facade. The fireplace and chimney were built by local grocer and jack-of-all-trades Harry Erickson, Sr., who built several other stone chimneys on Rainy Lake.

Nowhere is there evidence of the efficient orthogonal site organization typical of northern Minnesota lake cabin sites. Typical of Japanese houses, the cabin has a moderate pitch to the roof. The picturesque appearance is substantially a result of the assemblage of various roof forms. The additions are deferential and supplemental to the main roof. Across the front extends the essential veranda. Characteristic of Japanese residential construction, the cabin has no foundation other than simple dry-laid stones.

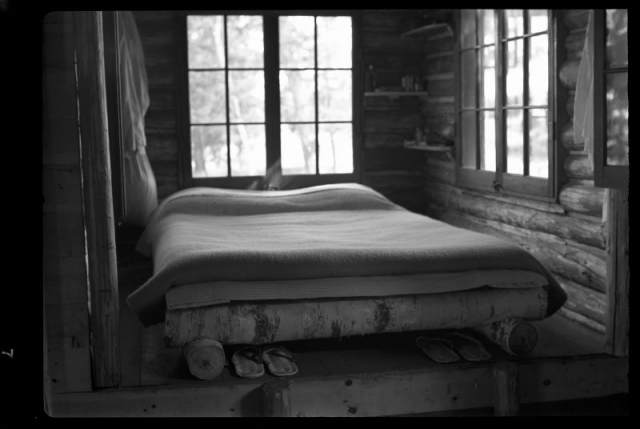

The sleeping alcove in Jun Fujita’s cabin, 1939. Graham and Pamela Lee Collection.

The use of natural materials, simple lines, light construction, little decoration, subdued colors, create a certain daintiness or grace in the construction that is suggestive of Japanese architecture. While the core cabin uses a simple post and beam system to carry the roof, this is typical both of Japanese and local cabin building tradition, it is the additions that emphasize the Japanese character. Fujita took unusual care to obtain and place uniform appearing cedar logs for the additions. More care was given to produce a precise rhythm to the naturals material than to assembly for durability. It is conspicuous and unusual that the additions are more rustic than the original construction and largely disguise the simplicity of the original form.

Fujita allowed Fred and Edythe Sackett of Rapid City, owners of nearby Norway Island, to use his Rainy Lake cabin from the early 1940s. The Sacketts sought to buy the property, but Fujita and Carr refused to sell it to them until 1956. The Sacketts added a bedroom on the south side of the cabin about I960. The bedroom addition is of frame construction and runs the entire width of the cabin.

Additional Photography by Jun Fujita

- A collection of Jun's 1957 nature photographs by Art Institute Chicago

- A collection of Jun's news photographs by Chicago History Museum

Researched and written by Joe Gruzalski with special thanks to Graham Lee, author of the upcoming book on his great-uncle, "Jun Fujita: Behind the Camera."