Last updated: January 29, 2025

Person

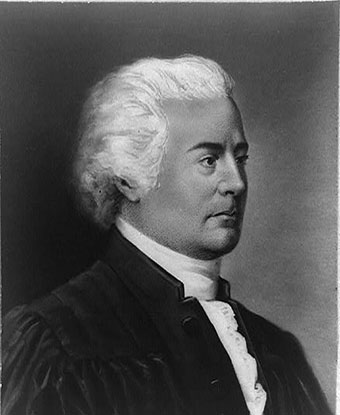

John Rutledge

Library of Congress

The eldest son of Dr. John Rutledge and Sarah Hext, John Rutledge studied law with his uncle Andrew Rutledge and with James Parsons in Charleston before attending the Middle Temple in London. Admitted to the South Carolina Bar in 1761, he quickly became one of the most successful attorneys in the colony. On May 1, 1763 he married Elizabeth Grimké. They had ten children, eight of whom survived to adulthood.

Rutledge served in the Commons House of Assembly from 1761 to 11775 and became one of its leaders. He upheld the political rights of fellow colonists as British subjects in a series of disputes with royal governors and firmly opposed the Stamp, Townshend, and Tea Acts, representing South Carolina at the Stamp Act Congress in 1765. As a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses, he advocated defending the rights of colonists while personally hoping for reconciliation with Great Britain. When events made reconciliation impossible, he reluctantly accepted independence as the path forward. Later in the debate over independence at the Continental Congress, his brother, Edward Rutledge, swayed his fellow South Carolinians to vote unanimously in favor of independence.

As royal authority dissolved in his own and other colonies, Rutledge supported a congressional resolution for the creation of new governments based on constitutions created by the people, not royal charters, until the crisis was resolved. He left Congress in November 1775 to carry that resolution to South Carolina. Rutledge was one of the drafters of the state constitution of 1776 and was elected president (governor) of South Carolina in March 1776. Under his leadership, the new state repulsed a British attack on Charleston in June 1776 and suppressed a Cherokee uprising later that summer.

Rutledge resigned as governor in March 1778 to protest adoption of a new state constitution of which he disapproved, but he was elected governor under that constitution in February 1779. When the British captured Charleston and established posts throughout South Carolina in 1780, Rutledge escaped and functioned as a one-man government in exile. He twice visited Philadephia to seek additional aid for the South but spent most of his time with the Continental Army in the South to organize and supply his state's militia for continued resistance. Eventual military sucesses in the South allowed him to restore state government and turn over the governorship to his successor, John Mathewes, In January 1782.

After serving again in Congress from 1782 to 1783, Rutledge accepted appointment to the South Carolina Court of Chancery, and he remained a leader in the state legislature in the 1780s. His experience in Congress convinced him that the United States needed a stronger central government. He was chosen as one of South Carolina's delegates to the constitutional convention in 1787.

Rutledge played a role in writing the federal Constitution. He advocated a national government of increased but limited powers and envisioned an executive and a Congress composed of gentlemen made relatively independent of public opinion. As chairman of the committee of detail, he had a major role in the enumeration of congressional powers, the provision forbidding taxation of exports, and the ban on national prohibition of slave imports until 1808. Rutledge promoted the adoption of the constitution at South Carolina's ratification convention.The people of South Carolina and Georgia “would never be such fools as to give up so important an interest.” John Rutledge, South Carolina delegate, 1787 referring to slavery

In 1789, Rutledge accepted appointment as one of the first justices of the US Supreme Court. He resigned from the position in 1791 to become chief justice of South Carolina, an office he held until 1795. In the early 1790s, Rutledge faced multiple serious personal problems. Large debts threatened the loss of all of his property. His health was severely damaged. His wife's sudden death in 1792 plunged him into depression.

Unaware of Rutledge's problems, President George Washington appointed him chief justice of the US Supreme Court in 1795. However, before learning of his nomination, Rutledge made a speech denouncing the recently negotiated Jay Treaty with Great Britain. This speech infuriated Federalists, and combined with reports of his depression and financial problems, the Federalist-dominated Senate rejected his nomination. Likely before hearing of the rejection, a depressed Rutledge attempted suicide and then resigned from the South Carolina Supreme Court for health reasons. Except for one term in the South Carolina House of Representatives, Rutledge remained in retirement until his death on July 18, 1800.