Last updated: April 12, 2022

Person

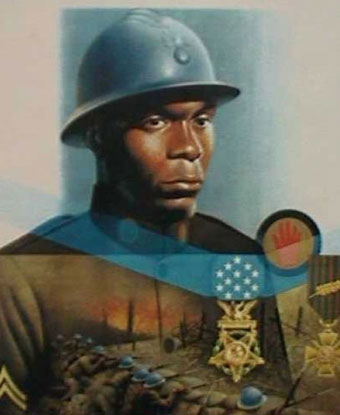

Freddie Stowers

South Carolina Military Museum

Freddie Stowers was born January 12, 1896, in Sandy Springs, South Carolina. Before being drafted he worked on the family farm. He was married to Pearl, and they had a daughter named Minnie Lee. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1917 at 21 and assigned to the all- Black Company C, 1st Battalion, 371st Infantry regiment. They were organized at Camp Jackson, South Carolina.

In March 1918, General Pershing assigned the 371st Infantry along with other all-Black regiments including the Harlem Hellfighters to aid the beleaguered French forces during World War I. The French needed combat troops and were accustomed to deploying their own Black colonial troops. While American military leaders warned the French not to treat the 371st Infantry and other African Americans as they did white troops, the French ignored this advice and welcomed them into their fighting force. After they received training with French weapons, the 371st was attached to the 157th French Army, known as the “Red Hand Division.”

In the early morning hours of September 28, 1918, Corporal Stowers’s company was ordered to take the heavily defended Hill 188, overlooking Ardeuil-et-Montfauxelles in the Ardennes region of France, from the Germans. The Germans initially gave stiff resistance to the American charge. The Germans used mortars, machine guns, and rifle fire. The Americans continued their determined advance up the hill. Stowers and his comrades saw the Germans wave a white flag and try to surrender. The Americans moved closer to the Germans without firing, readying to take the Germans prisoners. At the last moment the Germans jumped back into their trenches and machine-gun fire again raked the Americans. Half of Stowers’s company was killed or wounded including his lieutenant and higher-ranked non-commissioned officers.

Corporal Stowers took command of the depleted company and urged them forward. Stowers and the remaining soldiers took the first German trench and neutralized one machine-gun position. As Stowers was leading his men to the second German trench, he was mortally wounded by German machine-gun fire. As he lay wounded, he urged his company forward to overtake the German position. The men forged ahead and dislodged the Germans from Hill 188. Stowers died there that day. He was buried along with 133 of his comrades at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial east of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon in France.

Shortly after Stowers was killed in action he was recommended for the Medal of Honor, but his application was misplaced, and the recommendation was never processed. Stowers’s heroic actions laid dormant in the annals of history until 1988. At that time the Army launched an investigation into why no African Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor in World War I. The investigation determined Stowers’s recommendation had fallen through the cracks. On April 24, 1991, President George H.W. Bush posthumously awarded Corporal Freddie Stowers the Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony. Stowers’s two sisters accepted the award on the family’s behalf.

The award to Stowers prompted the Army to continue to look through the records of World Wars I and II to see if the military had overlooked other African Americans deserving of the Medal of Honor. In total, seven African American World War II veterans were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1997. Only one other African American soldier who served in World War I, Henry Johnson, has posthumously received the Medal of Honor. His posthumous award occurred in 2015.

Corporal Freddie Stowers’s Medal of Honor citation reads:

“Corporal Stowers distinguished himself by exceptional heroism on 28 September 1918 while serving as a squad leader in Company C, 371st Infantry Regiment, 93d Division. His company was the lead company during the attack on Hill 188, Champagne Marne Sector, France, during World War I. A few minutes after the attack began, the enemy ceased firing and began climbing up onto the parapets of the trenches, holding up their arms as if wishing to surrender. The enemy’s actions caused the American forces to cease fire and to come out into the open. As the company started forward and when within about 100 meters of the trench line, the enemy jumped back into their trenches and greeted Corporal Stowers’ company with interlocking bands of machine gun fire and mortar fire causing well over fifty percent casualties. Faced with incredible enemy resistance, Corporal Stowers took charge, setting such a courageous example of personal bravery and leadership that he inspired his men to follow him in the attack. With extraordinary heroism and complete disregard of personal danger under devastating fire, he crawled forward leading his squad toward an enemy machine gun nest, which was causing heavy casualties to his company. After fierce fighting, the machine gun position was destroyed, and the enemy soldiers were killed. Displaying great courage and intrepidity Corporal Stowers continued to press the attack against a determined enemy. While crawling forward and urging his men to continue the attack on a second trench line, he was gravely wounded by machine gun fire. Although Corporal Stowers was mortally wounded, he pressed forward, urging on the members of his squad, until he died. Inspired by the heroism and display of bravery of Corporal Stowers, his company continued the attack against incredible odds, contributing to the capture of Hill 188 and causing heavy enemy casualties. Corporal Stowers’ conspicuous gallantry, extraordinary heroism, and supreme devotion to his men were well above and beyond the call of duty, follow the finest traditions of military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army.”