Last updated: February 27, 2024

Person

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

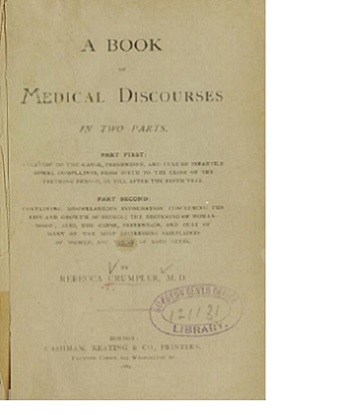

Public domain, courtesy U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first Black woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. A true pioneer, she battled deep-seated prejudice against women and African Americans in medicine. After earning her degree in Boston, she spent time in Richmond, Virginia after the American Civil War, caring for formerly enslaved people. In 1883, Dr. Crumpler published her Book of Medical Discourses. It chronicles her experiences as a doctor and provides guidance on maternal and child health.

Born Rebecca Davis in Delaware in 1831, Crumpler was raised by an aunt in Pennsylvania who often helped care for sick neighbors. Those early experiences made her want to work to "relieve the suffering of others." In the early 1850s she moved to Massachusetts and became a nurse.

Crumpler earned a place at the New England Female Medical College (NEFMC) in 1860. The school was the first in the country to train women M.D.s. At the time, many men argued that women were too delicate or not intelligent enough to be doctors. Most medical schools barred Black students regardless of gender.

The NEFMC initially trained women to work only as midwives. This focus reflected its founder Samuel Gregory's belief that it was improper for male doctors to assist with childbirth. But by the time Crumpler attended, the curriculum had expanded to encompass a more complete medical education.

Dr. Crumpler graduated from New England Female Medical College in 1864, becoming the first female African American doctor. Her official degree was "Doctress of Medicine." She began practicing in Boston, but at the end of the American Civil War found herself drawn to Richmond, Virginia as a "proper field for real missionary work." She collaborated with the Freedmen’s Bureau and other charity and missionary groups to care for freed African Americans. Many of her patients were very poor people who would otherwise have had no access to medical care. The enormous needs of these patients, and the discrimination they faced from many white doctors, encouraged an increasing number of African Americans to seek medical training.

Dr. Crumpler continued to practice after returning to Boston in the late 1860s. She treated patients in and around her home on Joy Street in Beacon Hill, at the time a mainly Black neighborhood, and regardless of whether they could pay.1 Later she and her second husband moved to the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston. In 1883, she published A Book of Medical Discourses. It features advice on treating illnesses in infants and young children and women of childbearing age.

Dr. Crumpler married twice and had one child, Lizzie Sinclair Crumpler. She passed away in Boston in 1895 and is buried in Fairview Cemetery.2 Her life and work testify to her talent and determination to help other people, in the face of doubled prejudice against her gender and race.

Footnotes

- Crumpler's home in Beacon Hill is featured on the Boston Black Heritage Trail, part of the Boston African American National Historic Site.

- Fairview Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 16, 2009.

Bibliography

“Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler.” Changing the Face of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_73.html.

Crumpler, Rebecca Lee. A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, 1883. https://archive.org/details/67521160R.nlm.nih.gov/page/n7/mode/2up.

Gardner, Martha N. Midwife, Doctor, or Doctress?: The New England Female Medical College and Women's Place in Nineteenth-Century Medicine and Society. Dissertation. Brandeis University, 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Microform, 2002.

Herwick, Edgar B. “The ‘Doctresses of Medicine’: The World’s 1st Female Medical School Was Established in Boston,” November 4, 2016. WGBH.org. https://www.wgbh.org/news/2016/11/04/how-we-live/doctresses-medicine-worlds-1st-female-medical-school-was-established-boston.

Pfatteicher, Sarah K. A. “Crumpler, Rebecca.” In African American Lives, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, 199-200. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.