The issue of slavery in the United States was settled by four years of slaughter. Out of the Civil War came the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring free the slaves in much of the Confederacy; and war's end saw passage of the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery throughout the nation. But the abolition of slavery created a great new question: What would be the political, economic, and social roles of the now-free black American?

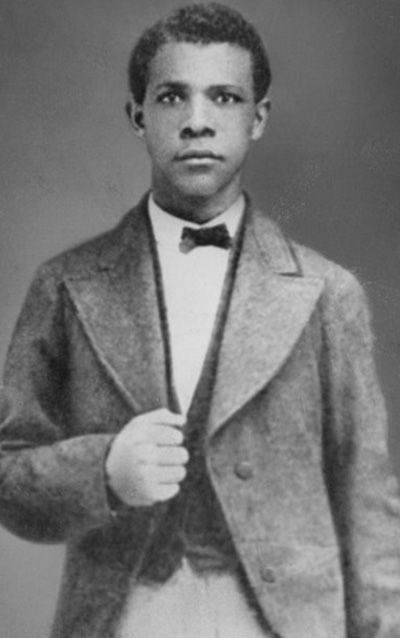

National Park Service, Booker T. Washington National Monument

During the postwar Reconstruction period, the federal government attempted to guarantee the former slaves those rights enjoyed by other American citizens. The Freedmen's Bureau, established by Congress in 1865 to assist the recently emancipated slaves in their transition to freedom, distributed food and clothing, offered medical services and educational aid, and worked to protect the freedmen from serfdom and violence. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 declared that African Americans are U.S. citizens entitled to equal treatment before the law. The 14th Amendment forbade the states to abridge the rights of any person without due legal process. An 1867 Reconstruction Act forced the former Confederate states to extend the franchise to African Americans. Racial discrimination in granting the vote was prohibited by the 15th Amendment in 1870. The final attempt at Reconstruction legislation was the Civil Rights Act of 1875, providing for "the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theatres, and other places of public amusement . . . Applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude."

These federal actions to extend the privileges of citizenship to freedmen were met with bitter resistance in the South and apathy in the North. Freedmen's Bureau activities were condemned as unjust interference in private affairs. White Southerners especially detested black participation in the reconstruction of state governments. To discourage African American political activity, they formed secret terrorist societies, such as the Ku Klux Klan, to intimidate those blacks attempting to exercise their rights. The federal government legislated against such tactics, but it was largely unsuccessful in enforcing measures to protect the freedmen.

Perhaps Reconstruction's greatest shortcoming was its failure to anticipate the economic needs of freedom. Millions of ex-slaves, possessing little more than the ragged clothing on their backs, were at the mercy of their former masters for survival. Amid the general poverty of the South at war's end, wages paid to freedmen in 1867 were lower than those paid earlier for hired slaves. Under the sharecropping system in which the agricultural worker received life's bare necessities and a share of the crop in exchange for his labor, blacks, as well as poor whites, became permanently indebted to the landowner for their maintenance. The Freedmen's Bureau tried to help by leasing and selling land to blacks and by supervising labor contracts, but Congress discontinued the Bureau's activities in 1872.

Library of Congress

The end of Reconstruction came with the administration of President Rutherford B. Hayes, who, in 1877, ended the role Federal troops had played in governing the South. Hayes' decision to leave protection of the freedmen's constitutional rights to "the great mass of intelligent white men" was received favorably, even in the North.

In that materialistic era of business expansion, few Northern whites wished to prolong sectional strife by interfering in what was increasingly viewed as a Southern concern; greater advantage would come from a nation united in the common pursuit of financial gain.

Freed from federal intervention, "the great mass of intelligent white men" chose to disregard African American voting rights. By 1889, Southern spokesman Henry W. Grady was able to state that "The Negro as a political force has dropped out of serious consideration." Black disfranchisement, achieved largely by fraud and intimidation, was legalized for the future by cleverly devised state constitutional amendments. Mississippi required voter registrants to give a "reasonable interpretation" of a clause from her constitution-with the registrar as judge. Louisiana established property and educational requirements for voting, along with a means of applying them to blacks only-the famous "Grandfather Clause." (This clause exempted from these requirements men entitled to vote, or whose ancestors could vote, in 1867. Few Louisiana blacks had voted at that time.) Other states followed suit, effectively removing almost all Southern blacks from the voting rolls by 1910. South Carolina's Senator Ben Tillman boasted: "We have done our best. We have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it."

Black advancement was further hampered by a variety of Supreme Court decisions against Reconstruction legislation, including the 1875 Civil Rights Act which guaranteed African Americans equal rights in public places and allowed them to serve on juries. After this act was declared unconstitutional in 1883, racial segregation-ordered by state laws, "Jim Crow" railway regulations, and custom-gradually became the rule throughout the South. Blacks were relegated to the poorest facilities on trains, on wharves, and in depots, and were banned from white hotels, restaurants, and theaters. Most damaging to their economic progress was the exclusion of blacks from most trade and labor organizations. Since they were usually forced to work for lower wages and were used by employers as strikebreakers, blacks were considered a threat to white workers and became a natural target for discrimination.

Many whites - North and South - sought justification for discriminatory practices in the common belief that blacks were inherently inferior. Senator Tillman, whose colorful, demagogic language often reflected the prejudices of more "moderate" men, described blacks as "akin to the monkey" and an "ignorant and debased and debauched race."

Contemporary books about the black man carried such titles as The Negro: A Beast and The Negro: A Menace to American Civilization, and at best, portrayed him as a simple-minded, happy-go-lucky character, content in his "proper" and accustomed role of serving the white master. Education might help him in a limited way, but, as one writer stated, "no amount of education of any kind, industrial, classical or religious, can make a Negro a white man or bridge the chasm of the centuries which separate him from the white man in the evolution of human civilization."

Such attitudes naturally contributed to widespread disrespect for due process of law as applied to black Americans. More than 3,000 blacks were lynched for major and minor offenses, real and imagined, between 1882 and 1900-most of them in the South, where the great majority of African Americans lived. Reaction of African Americans to a society in which they were held in general contempt, and in which laws, courts, schools, and almost every other institution favored the white man, could hardly be expected to be favorable. In 1903, white historian John Spencer Bassett wrote: "There is today more hatred of whites for blacks and blacks for whites than ever before." Black author Charles W. Chesnutt was equally pessimistic: "The rights of the Negroes are at a lower ebb than at any time during the thirty-five years of their freedom, and the race prejudice more intense and uncompromising."

Politically, blacks were all but silenced. Economically, most of them were barely subsisting. Socially, they were ostracized as a separate, inferior order of humanity. Such were the circumstances that confronted and shaped the career of Booker T. Washington.

Last updated: August 14, 2017