Last updated: January 29, 2025

Person

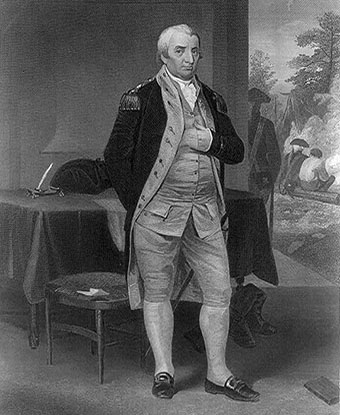

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Library of Congress

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, born to a prominent family of South Carolina's Lowcountry, had a long career as a politician and served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. He was also a signer of the US Constitution and twice nominated as the Federalist candidate for the presidency, losing to Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in 1804 and 1808.

Pinckney was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1746 to Charles Pinckney, a lawyer and member of the provincial council, and Elizabeth (Eliza) Lucas, who helped introduce indigo cultivation in South Carolina. In 1753, Pinckney accompanied his family to London, where his father served as the colony's agent until 1758. Pinckney received an excellent education in England, first attending Westminster School, and then Christ Church College, Oxford, and the Middle Temple. His legal training at the Middle Temple prepared him for a thriving legal practice when he returned to South Carolina in 1769. He also entered public service when he returned home, representing St. John's Colleton Parish during the remainder of royal rule. Pinckney also served in the South Carolina militia, attaining the rank of colonel.

On September 28, 1773 Pinckney married Sarah Middleton, daughter of the wealthy and well connected Henry Middleton. The marriage produced four children. Through this marriage, Pinckney joined a circle of revolutionaries in the South Carolina Lowcountry, including Arthur Middleton, Edward Rutledge, and William Henry Drayton. By early 1775, Pinckney was a member of all the important committes. He especially advocated for the preparation of Charleston harbor defenses against potential British attack and supported training a colonial patriot-supporting army.

Once hostilities erupted with Great Britain, Pinckney turned his attention entirely to military matters. He commanded the First South Carolina Regiment during the Battle of Sullivan's Island in late June 1776 but did not participate directly in the battle. Pinckney later joined the northern army under General George Washington and saw combat in the battles around Philadephia at Brandywine and Germantown. When the British refocused their strategy on the south, Pinckney returned to the Southern Department and commanded a regiment at the siege of Savannah. During the siege of Charleston in 1780, Pinckney commanded the garrison at Fort Moultrie, which fell to the British without a fight on May 7. With the surrender of Charleston and the Royal army defending it, the British placed Pinckney under house arrest at Snee Farm with General William Moultrie and attempted to lure him away from the patriot cause. Pinckney was prisoner-exchanged in Philadelphia in 1782. He rejoined the southern army but saw no further action. After his first wife Sarah Middleton died in 1784, Pinckney married Mary Stead in 1786.

Following the war, Pinckney turned his attention to rebuilding his law practice and his rice plantations. In 1787, he served as one of four South Carolinian delegates to the Constitutional Convention, where he defended the interests of southern slaveholding planters and argued for the retention of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Pinckney argued that "while there remained one acre of swampland uncleared of South Carolina, I would raise my voice against restricting the importation of negroes....the nature of our climate and the flat, swampy situation of our country, obliges us to cultivate our lands with negroes, and that without them South Carolina would soon be a desert waste...” Pinckney also commented on the irony and duality of American freedom and American slavery when he said, "Bills of rights generally begin with declaring that all men are by nature born free. Now, we should make that declaration with a very bad grace, when a large part of our property consists in men who are actually born slaves."

A Federalist, Pinckney was a leading figure in South Carolina's ratification of the new federal Constitution in 1788. He later drafted his state's 1790 constitution. Offered positions in President George Washington's cabinet, Pinckney refused all the offices. Pinckney accepted the post of Minister to France in 1796. He assumed the position during a difficult time in Franco-American relations as the Jay Treaty with Great Britain angered France. Additionally, the French First Republic directed its navy to seize American merchant ships engaged in trade with Great Britain. When Pinckney arrived to present his credentials to the French government, the French informed him that no American minister would be recognized during the current crisis which outraged. Pinckney was outraged. The next year, President John Adams appointed him as one of three commissioners to negotiate a treaty with the French government. When French diplomats demanded a bribe from their American counterparts to faciliate negotiations, Pinckney is credited as exclaiming, "No, no, not a sixpence!" and urged his government to raise "millions for defense but not one cent for tribute." This episode of American and French hostility, known as the XYZ Affair, led to the Quasi-War with France and strained Adams' presidency.

In 1798, with Pinckney back in America, President Adams, anticipating war with France, appointed him as commander of the southern department of the US Army. Pinckney was discharged from service in 1800. Pinckney returned to politics in 1800 as the Federalist Party's vice presidential candidate. In 1804 and 1808, he was the Federalist candidate for president, but he never actively campaigned. Pinckney devoted the remainder of his life to his plantations and agricultural science, civic service, and helped establish the South Carolina College in 1801. Pinckney died on August 16, 1825 in Charleston.