|

The Marine Rearguard on Bataan

Three days after the bombardment of Cavite,

Lieutenant Colonel William T. Clement, Fleet Marine Officer, U.S.

Asiatic Fleet, was summoned to Manila for talks with General Douglas

MacArthur and his chief of staff, Major General Richard K. Sutherland.

Both Army generals were persistent in their efforts to obtain the

release of the Marines in the Philippines from Navy to Army control.

MacArthur wanted a battalion of Marines to relieve a battalion of the

31st U.S. Infantry to guard his U.S. Army Forces in the Far Fast

(USAFFE) Headquarters and to occupy a section of the Philippine

capital.

This matter was successfully resisted until 20

December. The rapid advance of the Japanese southward from Lingayen Gulf

led the USAFFE commander to abandon Manila and to declare it an open

city. He departed on 24 December, and on the following day located an

administrative USAFFE Headquarters in Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor.

However, some Marines were still destined to perform

guard duty for the U.S. Army. On 5 January 1942, MacArthur established a

forward tactical USAFFE echelon on Bataan, under the command of

Brigadier General Richard J. Marshall. It was sited at KM (Kilometer)

187.5, northwest of Mariveles, near a quarry at the junction of West

Road and Rock Road. On the following day newly promoted Marine First

Lieutenant William F. Hogaboom, commanding antiaircraft Battery A, 3d

Battalion, 4th Marines, from Cavite, mounted out an interior guard

there.

Lieutenant Hogaboom was relieved of this duty on 16

January, when his battery received new orders to join the Naval

Battalion at the Quarantine Station at Mariveles. For the next month or

so, Marine Batteries A and C were a part of this battalion engaged in

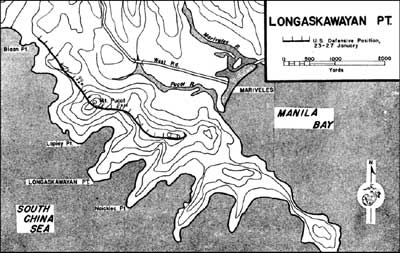

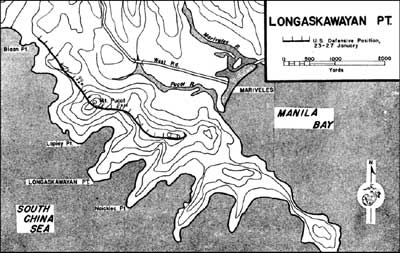

combat with a Japanese landing force which had come ashore on

Longoskawayan Point behind the American lines.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

On 10 January, General MacArthur made his only visit

to the front lines on Bataan. Six days later, First Lieutenant Ralph C.

Mann, Jr., Company F; and First Lieutenant Michiel Dobervich, Company E,

received verbal orders from Lieutenant Colonel Herman R. Anderson,

commanding the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines, on Corregidor, to establish a

new guard at the forward USAFFE echelon, now called Signal Hill. The

detachment consisted of 43 Marines, apparently selected at random from

throughout the 4th Marines, together with five Filipinos.

The Marine guard had just completed its security

precautions when another Japanese force landed at Aglaloma Point to the

north and sent patrols forward toward Pucot Hill. Sniper fire was

received from two directions at the

headquarters on 24 January Lieutenant Dobervich led a

patrol of 11 Marine riflemen and one Browning Automatic rifleman out to

Pucot Hill seeking any enemy who may have infiltrated the Naval

Battalion's lines. No contacts were made and the patrol returned at

dark.

The USAFFE Headquarters moved inland on 27 January,

reportedly because of proximity to the offensive being conducted in the

vicinity of Pucot Hill and Longoskawayan Point. The new location was KM

167.5, north of the road exiting Mariveles to Bataan's East Road and

east of Hospital No. 1. The site was nicknamed "Little Baguio," after

the elite summer resort in northern Luzon.

Dobervich described the area as that occupied by

USAFFE's Service Command, the headquarters compound being entered

through a motor pool north of the highway. An ammunition dump was

located to its east side, dangerously near the hospital. Facilities were

sparse, one or two corrugated buildings and squad tents clustered

beneath a towering canopy of trees, effectively screened from aerial

observation. The Marines' tent camp and mess were located north of the

headquarters. The whole was situated on a flat arm of an extinct volcano

southeast of the Mariveles Mountains.

Marines in the detachment with bolos cut a perimeter

path from the jungle around the headquarters at approximately 500 yards

from the outermost structure. Barbed wire was implanted on the outside

and smooth wire inside the path to guide sentries in the darkness. Rocks

in cans mounted on trip wires strung outside the wire were occasionally

disturbed by iguanas, wild pigs, and pythons. Marines manned eight

outposts in the perimeter. Watches were four hours on, four off.

Several Marines later testified to the tedium of this

duty. There were no incursions this far south by infiltrating Japanese.

By this time, rations had been cut more than half, and the content of

the ration apparently varied with in the command structure. Private

First Class James O. Faulkner compared the tantalizing smell of frying

bacon in the commanding general's cook tent to the unappetizing and

unsalted messkit of boiled rice he was repeatedly issued from one day to

the next. Apparently some Marines messed with the Army; others recall

having gotten all their meals from the Marine galley. The former were

probably one sergeant, one corporal, and two privates first class who

were assigned as radio operators at Station WTA, USAFFE Headquarters,

from January through mid-March.

Former Private Earl C. Dodson was a driver for

Lieutenant Mann and acted as mess sergeant. Several of their trips were

to acquire rations from the Navy tunnels at Mariveles. He recalls their

vehicle being repeatedly strafed by the Japanese. He said that the

lieutenant tried to get transferred to Marine antiaircraft duty, feeling

that his talents were being wasted in the guard detachment. Mann worried

about his wife, the daughter of an American official in the consul's

office in Shanghai, whom he had married there. Mrs. Mann accompanied him

to the Philippines in November 1941 and was now a prisoner of the

Japanese in Manila.

Lieutenant Dobervich also made trips for supplies,

traveling three times to Corregidor, where his friend, First Lieutenant

Jack Hawkins, Company H, 2d Battalion, assisted him in acquiring them.

However, at the end of February, Dobervich was laid up with malaria for

two weeks at Hospital No. 1.

On 22 February, Washington notified General MacArthur

that he was relieved as commander in the Philippines and that he was to

make his way to Australia. Command of the Philippines devolved onto

Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright, of I Corps, and USAFFE was

redesignated U.S. Forces in the Philippines (USFIP). When MacArthur

departed on 12 March, Wainwright took command of the newly formed Luzon

Force at the Little Baguio headquarters. However, when he was promoted

to lieutenant general on 20 March, he moved to USFIP Headquarters in

Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor. Wainwright selected Major General Edward

P. King, Jr., to command Luzon Force Headquarters and its combat

forces.

Late in March, MacArthur urged Wainwright by radio to

make a major counter-attack northward with both his corps to capture

Japanese supplies at Olongapo and Dinalupihan. Before any such plans

could be formulated, the enemy struck first with fresh troops. Japanese

aircraft became more aggressive, one strike coming straight to Hospital

No. 1, plainly marked with a Red Cross, and bombing it without mercy.

Manila's Japanese radio announced on 31 March that the raid was

"unintentional," but the mistake was repeated in following days.

Luzon Force Headquarters and its Marine Detachment

came in for their share of subsequent bombings, and Japanese artillery

began to find the range. Lieutenant Dobervich urged his Marines to dig

foxholes and trenches and directed that a large shelter be tunneled into

a nearby hillside. This was enlarged until the Marines turned miners ran

into a huge rock in their path which discouraged further progress.

The Japanese Easter offensive broke through the front

lines between the two corps on Good Friday and armed barges struck the

rear flanks from Manila Bay. By 8 April, the II Corps eastern front had

become chaos and, unknown to Wainwright, General King determined to

surrender Bataan's battered remnants. Marines at the Luzon Force state

that they were aware of some of the proceedings, that they saw officers

in a staff car with a white flag depart the camp and proceed northward

through streams of troops retreating southward.

At about 2130, 8 April, a severe earthquake shook the

peninsula, and the Marines retreated into their prepared tunnel. An hour

later, the first of many explosions occurred, when the Navy blew up the

USS Canopus, the Dewey Drydock, and its other installations at

Mariveles. Army demolition followed, TNT charges setting off the

ammunition dump between headquarters and Hospital No. 1 and engineer and

quartermaster stores in the adjacent Service Command. The blasts upset

the headquarters building, scattering its furniture. At daylight, it was

found that all the overhead tree cover had disappeared. On emerging from

their sanctuary, the Marines found the rock blocking their tunnel

dislodged and free, and they considered themselves fortunate at not

being buried alive.

Dovervich recalls that someone on General King's

staff advised the other officers to remove their insignia of rank, or to

hide it in their clothing. They were also told to rid themselves of any

Japanese souvenirs or currency. One Army officer did not, and Dobervich

later witnessed his execution. Some enlisted men say they stacked their

arms. Others threw their rifle bolts into the jungle and mangled or

completely destroyed the remainder of their small arms. All remaining

rations were issued. Some gorged, but others made an attempt to hide and

save them for a later time. It seems that no one thought to acquire

extra water, for they had no way of knowing what lay ahead. They sat

down to await the arrival of the Japanese.

Richard A. Long

|