| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

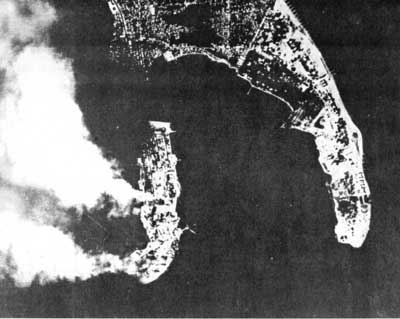

FROM SHANGHAI TO CORREGIDOR: Marines in the Defense of the Philippines by J. Michael Miller Bombing of Cavite Three Marine-manned antiaircraft positions were located outside the Cavite Navy Yard: Battery A, across the bay at Canacao Golf Course on the tip of Sangley Point; Battery B at Carridad; and Battery C at Binacayan one mile south. Each held four 3-inch, .50-caliber, dual-purpose guns with a range of about 15,000 feet. Battery D was divided to support each position with five .50-caliber machine guns. On 10 December, two Japanese combat teams came ashore in northern Luzon, securing airfields for their Army aircraft to support more landings. However, there was no alarm in Cavite. As usual, civilian workers came into the Navy Yard and quickly went to work. The only sign of war was a detachment of Filipino workers digging an air-raid trench in the yard of the Commandancia, Admiral Rockwell's headquarters. The half-completed trench was the only air-raid shelter in the Navy Yard. Only the antiaircraft weapons had been revetted. Four 3-inch antiaircraft guns were mounted at the ammunition depot in the yard, as well as numerous .50-caliber machine guns mounted around the yard.

A little past noon the droning of numerous aircraft engines was heard, followed by an air-raid siren. Marines rushed to the veranda of the Marine Barracks and watched 54 aircraft in three large "V" formations approach. All eyes in the Yard were focused on the aircraft which were widely assumed to be Army Air Corps. The first suspicious sign was a dogfight below the formation. Someone then yelled, "Look at those leaflets come down." Almost in unison, many voices yelled out, "leaflets, hell — they're bombs!" The naval base was rocked by the first bombs striking the ground. Marines, sailors, and civilians crouched under the nearest cover with no formal shelters available. The first stick of bombs hit the water, as did most of the second, but the rest of the bombs criss-crossed the Navy Yard and small fires began to spread among the wreckage. The Marines of Battery E, on top of the Naval Ammunition Depot, opened fire as bombs hit first on one side of their building and then on the other, splashing mud and water over them. Private First Class Leslie R. Scoggin called out the plotting data for the nearby battery, but found the aircraft were flying above 23,000 feet, far above the range of the battery. Luckily, no bombs actually hit the depot. The Marine on the rangefinder at Battery C, stationed at Binacayan, reported to First Lieutenant Willard B. Holdredge that the aircraft were above the range of the guns. Holdredge ordered the Marine to take the reading again. When given the same answer, the lieutenant took the reading himself. Holdredge knew then that the Japanese aircraft were flying at 21,000-25,000 feet but his guns had a range of only 15,000 feet. He ordered the battery to fire anyway.

First Lieutenant Carter Simpson at Binacayan later wrote, "We were left with a sense of fatality which was renewed every time our eyes fell on the Yard across the bay . . . A toy pistol would have damaged their planes as much as we did." Battery A on Sangley Point ceased fire after the first wave passed untouched. Battery B on Carridad also tried to hit the Japanese aircraft, but the 280 rounds expended during the raid fell short. Captain Ted E. Pulos command ed Battery F, which had two .50-caliber machine guns located on the Guadalupe Pier near the Navy Communications building. He ordered his men to open fire on the first wave of planes, but after the initial bombing ordered his men to cease fire as the aircraft were obviously above range. Private First Class Thomas L. Wetherington was killed by bomb fragments, becoming the first Marine to lose his life in defense of the Philippines. Private First Class George Sparks was on guard duty at the Naval District Headquarters when the bombs hit. He was able to take cover in a worn path beside the building as the bombs began to fall. Trees were blown down and one fell over Sparks. Although the path was only a few inches deep, it was enough to save him from serious injury. One other Marine was wounded during the bombing. Captain John Clark ran to the barracks and ordered the Marines not on duty to draw ammunition and get outside to fire on enemy aircraft which might strafe the Yard. They ran to the quartermaster's office and formed in line to receive ammunition. As bombs fell nearby, the Marines dove for cover, and then returned to the line, repeating the process several times. Bombs struck close to them as Private Jack D. Thompson later remembered, "When you hear one of those bombs coming down, you think it's coming down the back of your neck." The effort proved fruitless as the buildings restricted the fields of fire for small arms. The Yard continued to burn as the last Japanese aircraft departed. An aid station was set up in the library of the Marine Barracks as the hospital had received a direct hit. Approximately 1,000 civilians were reported killed and more than 500 wounded were treated in the aid station. Marines formed firefighting parties to put out the raging fires. The Filipino fire companies surrounded the ammunition dump and prevented fire from reaching the explosives, but the torpedo warehouse burned and the warheads sporadically exploded, preventing the firefighting parties from putting out the fire. The fires trapped Captain Pulos' Battery F on the Guadalupe Pier and the exploding torpedo warheads threatened the Marines, sailors, and civilians who had escaped to the dock. Pulos ordered his Marines to build makeshift rafts and successfully evacuated men, weapons, and ammunition.

As night neared, all personnel, except a small group of Marines and Manila firemen, were evacuated out of the Yard and transported by truck to a site on the road leading to Manila. After travelling 15 miles the trucks stopped and the battalion set up camp. The following morning Marine detachments were sent back to guard the abandoned Navy Yard. Field kitchens were established to feed civilians as well as Navy and Marine Corps personnel. Other detachments reinforced the Sangley Point radio station as well as the ammunition depot at Canancao. Marines were also posted at all the gasoline stations on the road to Manila to guard the fuel supplies for military use. Marines patrolled the emptied Navy Yard, checking for looters and any new fires. At noon an administrative force returned and reopened the battalion offices. A bulldozer dug a trench near the Commandancia and working parties attempted to bury the civilian dead. Dump trucks were filled with bodies which were dumped into the trench as Marines buried more than 250 corpses with shovels. Once the burials in the Yard were finished, the mass grave was covered with dirt. The Cavite area remained quiet until 1247 on 19 December when nine Japanese bombers returned with Sangley Point as their target. The bombers hit the large radio towers and the fuel depot. Numerous 55-gallon fuel drums were stored on the golf course, in the hospital compound, and on the beach. Fuel drums exploded, forcing the evacuation of the wounded. One Marine remembered "the roar of the fire drowned the sound of the motors (of the bombers) and the sound of the bombs." Mess Sergeant Milton T. Larios, Corporal Earl C. Dodson, and a Filipino cook named "Pop" were preparing rations for the Marines still in the Cavite Navy Yard when the air-raid siren went off. Larios shouted, "Let's get this meat off the fire," and tried to load the beef into a nearby garbage can when the bombs hit. Corporal Dodson remembered running until hearing the whistle of the bombs coming down and then fell to the ground. Explosions covered him with dirt and debris but he escaped the blast unhurt. He ran back to the mess area where he found Larios dead and "Pop" dying. He carried the bleeding Filipino to a collection point where 15 wounded Americans and Filipinos were lying together. Admiral Rockwell ordered First Lieutenant James W. Keene to make a fire break in the rows of barrels to save as much fuel as possible. Keene took 12 Marines into the area of the exploding barrels and began work when another "stick" of bombs hit, killing Private First Class George D. Frazier. The bombs started new fires, which forced Keene to pull his men out. Total Marine casualties were five killed, eight wounded.

|