| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

BLOODY BEACHES: The Marines at Peleliu by Brigadier General Gordon D. Gayle, USMC (Ret) The Assault Continues With the dawn of a new day, the two opposing commanders at Peleliu awoke from whatever sleep they may have gotten to face immediate grim prospects. General Rupertus, having been frustrated by his earlier effort to land his division reserve into the southern sector of his beachhead, was now aware that his northern sector stood most in need of help, specifically on the extreme left flank. Rupertus ordered 2/7 into Puller's sector for employment there. At division headquarters afloat, more had been learned about the extent of Marine D-Day casualties: 1,111, of whom 209 were killed in action (KIA). While this was not a hefty percentage of the total reinforced divisional strength, the number was grim in terms of cutting-edge strength. Most of those 1,111 casualties had been suffered in eight of the division's nine infantry battalions. Except in the center, Rupertus was not yet on the 0-1 line, the first of eight planned phase lines.

Having received less than a comprehensive view of the 1st Marines' situation, Rupertus was more determined than ever to move ashore quickly, to see what he could, and to do whatever he could to re-ignite the lost momentum. That he would have to operate with a gimpy leg from a sandy trench within a beach area still under light but frequent fire, seemed less a consideration to him than his need to see and to know (General Rupertus had broken his ankle in a preassault training exercise, and his foot was in a cast for the entire operation.). Over on Colonel Nakagawa's side, despite the incredible reports being sent out from his headquarters, he could see from his high ground a quite different situation. The landing force had not been "put to route." Ashore, and under his view, was a division of American Marines deployed across two miles of beach head. They had been punished on D-Day, but were preparing to renew the fight. Predictably, their attack would be launched behind a hail of naval gunfire, artillery, and aerial attacks. They would be supported by U.S. tanks which had so readily dispatched the Japanese armor on D-Day.

In his own D-Day counterattack, Nakagawa had lost roughly one of his five infantry battalions. Elsewhere he had lost hundreds of his beach defenders in fighting across the front throughout D-Day, and in his uniformly unsuccessful night attacks against the beachhead. Nevertheless, he still had several thousand determined warriors, trained and armed. They were deployed throughout strong and well-protected defensive complexes and fortifications, with ample underground support facilities. All were armed with the discipline and determination to kill many Americans. As he had known from the start, Nakagawa's advantage lay in the terrain, and in his occupation and organization of that terrain. For the present, and until that time when he would be driven from the Umurbrogol crests which commanded the airfield clearing, he held a dominating position. He had impressive observation over his attackers, and hidden fire to strike with dangerous effect. His forces were largely invisible to the Americans, and relatively impervious to their fire superiority. His prospects for continuing to hold key terrain components seemed good. The Marines were attacking fortified positions, against which careful and precise fire preparations were needed. They were, especially on the left, under extreme pressure to assault rapidly, with more emphasis upon speed than upon careful preparation. With enemy observation and weapons dominating the entire Marine position, staying in place was to invite being picked off at the hidden enemy's leisure. General Rupertus' concern for momentum remained valid. This placed the burden of rapid advance primarily upon the 1st Marines on the left, and secondarily upon the 5th in the airfield area. In the south, the 7th Marines already held its edge of the airfield's terrain. The scrub jungle largely screened the regiment from observation and it was opposed by defenses oriented toward the sea, away from the airfield.

Puller's 1st Marines, which had already suffered the most casualties on D-Day, still faced the toughest terrain and positions. It had to attack, relieve Company K, 3/1, on the Point, and assault the ridges of Umurbrogol, south to north. Sup porting that assault, Honsowetz had to swing his east-facing 2/1 leftward, and to capture and clear the built-up area between the airfield and the ridges. This his battalion did on D plus 1 and 2, with the 5th Marines assisting in its zone on the right. But then he was at the foot of the commanding ridges, and joined in the deadly claw-scratch-and-scramble attack of Davis' 1/1 against the Japanese on and in the ridges. As Colonel Puller was able to close the gaps on his left, and swing his entire regiment toward the north, he pivoted on Sabol's 3/1 on the left. Sabol, aided by Company B, 1/1, established contact with and reinforced Company K on the Point. Then he headed north, with his left on the beach and his right near the West Road along the foot of the western most features of the Umurbrogol complex. In Sabol's sector, the terrain permitted tank support, and offered more chances for maneuver than were afforded in the ridges further to the right. Hard fighting was involved, but after D-Day, Sabol's battalion was able to move north faster than the units on his right. His advance against the enemy was limit ed by the necessity to keep contact with Davis' 1/1 on his right.

The relative rates of movement along the boundary between Sabol's flatter and more open zone and Davis' very rough zone of action, brought the first pressing need for reserves. Tactically, there was clear necessity to press east into and over the rough terrain, and systematically reduce the complex defenses. That job Davis' 1/1, Honsowetz's 2/1, and Berger's 2/7 did. But more troops than Sabol had also were needed to advance north through the open terrain to begin encirclement of the rough Umurbrogol area, and to find avenues into the puzzle of that rugged landscape. By 17 September, reserves were badly needed along the 1st Division's left (west) axis of advance. But on 17 September, neither the division nor III Amphibious Corps had reserves.

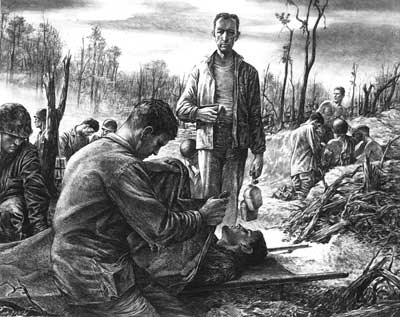

As Sabol's 3/1 fought up the easier terrain on the 1st Marines' left, Davis' 1/1 drove into the center with his left on the break between coral ridge country and Sabol's more open flat zone. Among his early surprises, as he approached the foot of the ridge area, was another of the blockhouses Admiral Oldendorf had reportedly destroyed with pre-D-Day gunfire. Although it had been on the planning map for weeks, those who first encountered it, reported the emplacement as "not having a mark on it." The blockhouse was part of an impressive defense complex. It was connected to and supported by a web of pillboxes and emplacements, which it in turn supported. The walls were four-feet thick, of reinforced concrete. Happily, Davis was given a naval gunfire support team which called in the fires of the the USS Mississippi. Between them, they made fairly short work of the entire complex, and 1/1 could advance until it ran into the far more insoluble Japanese ridge defense systems. Major Davis, who was to earn a Medal of Honor in the Korean War in 1950, said of the attack into and along or across those ridges, "It was the most difficult assignment I have ever seen." During the 1st Marines' action in the first four days of the campaign, all three of its battalions battled alongside, and up onto Umurbrogol's terrible, cave-filled, coral ridges. Berger's 2/7, initially in division reserve, but assigned to the 1st Marines on D plus 1, was immediately thrown into the struggle. Puller fed two separate companies of the battalion into the fight piecemeal. Shortly thereafter, 2/7 was given a central zone of action between Colonel Puller's 1st and 2d Battalions. The 1st Marines continued attacking on a four-battalion front about a 1,000 yards wide, against stubborn and able defenders in underground caves and fortifications within an incredible jumble of ridges and cliffs. Every advance opened the advancing Marines to new fire from heretofore hidden positions on flanks, in rear, in caves above or below newly won ground. Nothing better illustrated the tactical dilemmas posed by Umurbrogol than did the 19 September seizure of, then withdrawal from, Hill 100, a ridge bordering the so-called Horseshoe Valley at the eastern limit of the Pocket. It lay in the sector of Lieutenant Colonel Honsowetz' 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, to which Company B of Major Ray Davis' 1st Battalion was attached. Company B, 1/1, having landed with 242 men, had 90 men left when its commander, Captain Everett P. Pope, received Honsowetz' order to take what the Marines were then calling Hill 100. The Japanese called it Higashiyama (East Mountain). Initially supported by tanks, Pope's company lost that support when the two leading tanks slipped off an approach causeway. Continuing with only mortar support, and into the face of heavy defending mortar and machine-gun fire, Pope's Marines reached the summit near twilight, only to discover that the ridge's northeast extension led to still higher ground, from which its defenders were pouring fire upon the contest ed Hill 100. Equally threatening was fire from the enemy caves inside the parallel ridge to the west, called Five Brothers. In the settling darkness Pope's men, liberally supported by 2/1's heavy mortars, were able to hang on. Throughout the night, there was a series of enemy probes and counterattacks onto the ridge top. They were beaten off by the supporting mortars and by hand-to-hand brawls involving not only rifles but also knives, and even rocks, thrown intermittently with grenades, as supplies of them ran low. Pope's men were still clinging to the ridge top when dawn broke; but the number of unwounded Marines was by now down to eight. Pope was ordered to withdraw and was able to take his wounded out. But the dead he had to leave on the ridge, not to be recovered until 3 October, when the ridge was finally recaptured for good. This action was illustrative and prophetic of the Japanese defenders' skillful use of mutually supporting positions throughout Umurbrogol.

By D plus 4, the 1st Marines was a regiment in name only, having suffered 1,500 casualties. This fact led to a serious disagreement between General Rupertus, who kept urging Puller onward, and the general's superior, Major General Roy S. Geiger, III Amphibious Corps commander. Based on his own experiences in commanding major ground operations at Bougainville and Guam, Geiger was very aware of the lowered combat efficiency such losses impose upon a committed combat unit. On 21 September, after visiting Colonel Puller in his forward CP and observing his exhausted condition, and that of his troops, Geiger conferred in the 1st Division CP with Rupertus and some of his staff. Rupertus was still not willing to admit that his division needed reinforcement, but Geiger overruled him. He ordered the newly available 321st Regiment Combat Team (RCT), 81st Infantry Division, then on Angaur, to be attached to the Marine division. Geiger further ordered Rupertus to stand down the 1st Marines, and to send them back to Pavuvu, the division's rear area base in the Russell Islands. On 21 September (D plus 5), Rupertus had ordered his 7th Marines to relieve what was left of the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 1st Marines. By then, the 1st Marines was reporting 1,749 casualties. It reported killing an estimated 3,942 Japanese, the capture of 10 defended coral ridges, the destruction of three blockhouses, 22 pillboxes, 13 antitank guns, and 144 defended caves. In that fighting the assault battalions had captured much of the crest required to deny the enemy observation and effective fire on the airfield and logistic areas. Light aircraft had begun operating on D plus 5 from Peleliu's scarred, and still-under-repair airfield. With Purple Beach in American control, the division's logistical life-line was assured. Although the Japanese still had some observation over the now operating airfield and rear areas, their reduced capability was to harass rather than to threaten. Furthermore, the Marine front lines in the Umurbrogol had by now reached close to what proved to be the final Japanese defensive positions. Intelligence then available didn't tell that, but the terrain and situation suggested that the assault requirements had been met, and that in the Umurbrogol it was time for siege tactics. The Japanese defenders also learned that when aerial observers were overhead, they were no longer free to run their weapons out of their caves and fire barrages toward the beach or toward the airfield. When they tried to get off more than a round or two, they could count on quick counter-battery, or a much-dreaded aerial attack from carrier-based planes, or — after 24 September — from Marine attack planes operating from the field on Peleliu.

In the south, from D plus 1 through D plus 3, the 7th Marines was in vigorous assault against extensive fortifications in the rear of the Scarlet Beaches. These were defended by a full battalion, the elite 2d Battalion, 15th Regiment. Although isolated and surrounded by the Marines, this battalion demonstrated its skill and its understanding of Colonel Nakagawa's orders and mission: to sell Peleliu at the highest possible price. The 7th Marines attacked with 3/7 on the left and 1/7 on the right. They enjoyed the advantage of attacking the extensive and well prepared defenses from the rear, and they had both heavy fire support and the terrain for limited maneuver in their favor. Both sides fought bitterly, but by 1530 on 18 September (D plus 3), the battle was substantially over. The Marines had destroyed an elite Japanese reinforced infantry battalion well positioned in a heavily fortified stronghold. Colonel Hanneken reported to General Rupertus that the 7th Marines' objectives he had set for D-Day were all in hand. The naval gunfire preparation had been significantly less than planned. The difference had been made up by time, and by the courage, skill, and additional casualties of the infantry companies of 1/7 and 3/7. Now the 7th Marines, whose 2d Battalion was already in the thick of the fight for Umurbrogol, was about to move out of its own successful battle area and into a costly assault which, by this time, might have been more economically conducted as a siege.

|