| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

BLOODY BEACHES: The Marines at Peleliu by Brigadier General Gordon D. Gayle, USMC (Ret) At dusk, Hunt's Company K held the Point, but by then the Marines had been reduced to platoon strength, with no adjacent units in contact. Only the sketchy radio communications got through to bring in supporting fires and desperately needed re-supply. One LVT got into the beach just before dark, with grenades, mortar shells, and water. It evacuated casualties as it departed. The ammunition made the difference in that night's furious struggle against Japanese determined to recapture the Point.

The next afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Raymond G. Davis' 1/1 moved its Company B to establish contact with Hunt, to help hang onto the bitterly contested positions. Hunt's company also regained the survivors of the platoon which had been pinned at the beach fight throughout D-Day. Of equal importance, the company regained artillery and naval gunfire communications, which proved critical during the second night. That night, the Japanese organized another and heavier — two companies — counterattack directed at the Marines at the Point. It was narrowly defeated. By mid-morning, D plus 2, Hunt's survivors, together with Company B, 1/1, owned the Point, and could look out upon some 500 Japanese who had died defending or trying to re-take it.

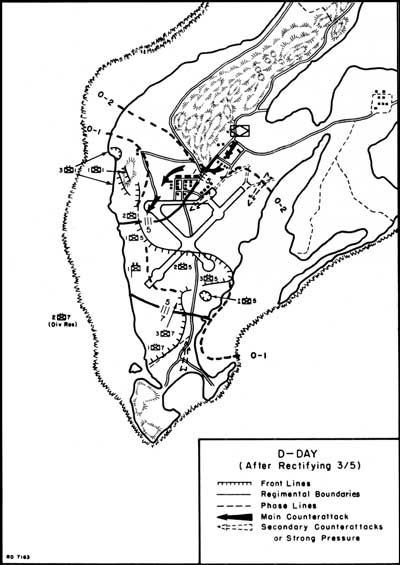

To the right of Puller's struggling 3d Battalion, his 2d Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Russell E. Honsowetz commanding, met artillery and mortar opposition in landing, as well as machine-gun fire from still effective beach defenders. The same was true for 5th Marines' two assault battalions, Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Boyd's 1/5 and Lieutenant Colonel Austin C. Shofner's 3/5, which fought through the beach defenses and toward the edge of the clearing looking east over the airfield area. On the division's right flank, Orange 3, Major Edward H. Hurst's 3/7 had to cross directly in front of a commanding defensive fortification flanking the beach as had Marines in the flanking position on the Point. Fortunately, it was not as close as the Point position, and did not inflict such heavy damage. Nevertheless, its enfilading fire, together with some natural obstructions on the beach caused Company K, 3/7, to land left of its planned landing beach, onto the right half of beach Orange 2, 3/5's beach. In addition to being out of position, and out of contact with the company to its right, Company K, 3/7, became intermingled with Company K, 3/5, a condition fraught with confusion and delay. Major Hurst necessarily spent time regrouping his separated battalion, using as a coordinating line a large anti-tank ditch astride his line of advance. His eastward advance then resumed, somewhat delayed by his efforts to regroup.

Any delay was anathema to the division commander, who visualized momentum as key to his success. The division scheme of maneuver on the right called for the 7th Marines (Colonel Herman H. Hanneken) to land two battalions in column, both over Beach Orange 3. As Hurst's leading battalion advanced, it was to be followed in trace by Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley's 1/7. Gormley's unit was to tie into Hurst's right flank, and re-orient southeast and south as that area was uncovered. He was then to attack southeast and south, with his left on Hurst's right, and his own right on the beach. After Hurst's battalion reached the opposite shore, both were to attack south, defending Scarlet 1 and Scarlet 2, the southern landing beaches. At the end of a bloody first hour, all five battalions were ashore. The closer each battalion was to Umurbrogol, the more tenuous was its hold on the shallow beachhead. During the next two hours, three of the division's four remaining battalions would join the assault and press for the momentum General Rupertus deemed essential.

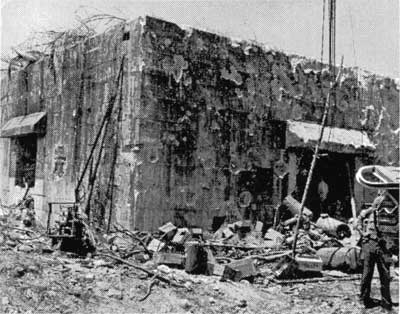

Following close behind Sabol's 3/1, the 1st Marines' Colonel Puller landed his forward command group. As always, he was eager to be close to the battle, even if that location deprived him of some capacity to develop full supporting fires. With limited communications, and now with inadequate numbers of LVTs for follow-on waves, he struggled to ascertain and improve his regiment's situation. His left unit (Company K, 3/1) had two of its platoons desperately struggling to gain dominance at the Point. Puller's plan to land Major Davis' 1st Battalion behind Sabol's 3/1, to reinforce the fight for the left flank, was thwarted by the H-hour losses in LVTs. Davis' companies had to be landed singly and his battalion committed piecemeal to the action. On the regiment's right, Honsowetz' 2/1 was hotly engaged, but making progress toward capture of the west edges of the scrub which looked out onto the airfield area. He was tied on his right into Boyd's 1/5, which was similarly engaged. In the beachhead's southern sector, the landing of Gormley's 1/7 was delayed somewhat by its earlier loses in LVTs. That telling effect of early opposition would be felt throughout the remainder of the day. Most of Gormley's battalion landed on the correct (Orange 3) beach, but a few of his troops were driven leftward by the still enfilading fire from the south flank of the beach, and landed on Orange 2, in the 5th Marines' zone of action. Gormley's battalion was brought fully together behind 3/7 however, and as Hurst's leading 3/7 was able to advance east, Gormley's 1/7 attacked southeast and south, against prepared positions. Hanneken's battle against heavy opposition from both east and south developed approximately as planned. Suddenly, in mid-afternoon, the opposition grew much heavier. Hurst's 3/7 ran into a blockhouse, long on the Marines' map, which had been reported destroyed by pre-landing naval gunfire. As a similar situation later met on Puller's inland advance, the blockhouse showed little evidence of ever having been visited by heavy fire. Preparations to attack and reduce this blockhouse further delayed the 7th Marines' advance, and the commanding general fretted further about loss of momentum.

|