| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

A DIFFERENT WAR: Marines in Europe and North Africa by Lieutenant Colonel Harry W. Edwards, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) After Pearl Harbor The Pearl Harbor attack on 7 December 1941, followed by a declaration of war on Germany and Japan, greatly accelerated the mobilization of U.S. naval forces in the Atlantic and Pacific Theaters. On 30 June 1941, the Marine Corps had 3,642 officers and 41,394 enlisted Marines, and was expanding at the rate of 2,000 enlistments a month. After Pearl Harbor, the enlistments exploded with 8,500 in December 1941, 13,000 in January 1942, and 10,000 in February. By June of that year, the strength of the Marine Corps had more than tripled. On 5 February 1942, the U.S. Navy established its first base on the European side of the Atlantic, in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, on the banks of the River Foyle. That forward base had become necessary be cause the fleet could not operate efficiently for any length of time more than 2,000 miles from a naval base.

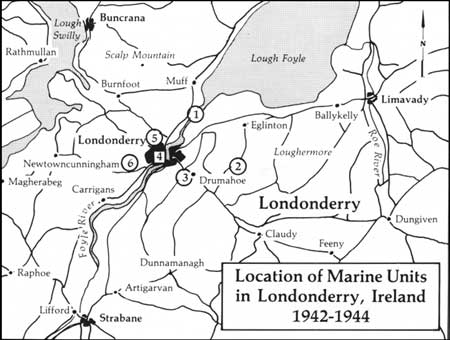

Upon arrival in Ireland, the unit was designated the Orders quickly followed for a Marine unit to provide security for this "naval operating base" (NOB) and the 1st Provisional Marine Battalion was organized in 1941 at Quantico, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Lucian W. Burnham. His executive officer was Major Louis C. Plain. In preparation, the Marines of that battalion received some rigorous and varied training, because one could not predict what duties their assignments would require of them. The 400-man battalion left the U.S. in May 1942, on the Santa Rosa, a converted cruise ship of the Italian-American line, headed across the North Atlantic for a destination known to very few. A month later, an augmentation force of 152 enlisted Marines arrived on board the SS Siboney, led by Second Lieutenant John S. Hudson. Marine Barracks, NOB, Londonderry, and assigned the mission to guard the dispersed facilities of the large base, which was about three miles from the city. Initially, the Marine Barracks was organized as follows: Headquarters and Service Company, under command of Major James J. Dugan; Company A, commanded by Captain John M. Bathum; and Company B, with Captain Frank A. Martincheck in command. In late October 1942, another draft of more than 200 men, with Second Lieutenant James B. Metzer in charge, arrived from the States on board the U.S. Army transport Boringuen. It became Company C. Meanwhile, several promotions took place in the unit — Bathum to major, Plain and Dugan to lieutenant colonel, four company officers to captain — and the battalion reorganized to add an additional company. Captain Donald R. Kennedy took over Company B and Captain George O. Ludcke received command of Company C.Colonel William A. Eddy, USMCR Another distinguished scholar who made his mark as a Reserve officer in the Marine Corps was Colonel William A. Eddy. Eddy became a Marine officer in 1917, after graduation from Princeton University. He saw action in France in World War I and received two Purple Hearts, a Navy Cross, the Distinguished Service Cross, and two Silver Star Medals. Between wars, he became a professor of English at Dartmouth College and, in 1936, the president of Hobart College and William Smith College, both in Geneva, New York. Returning for active duty with the Marines in 1941, he served successively with the Office of Naval Intelligence, as naval attache in Cairo, Egypt, and later in Tangier, and finally he assumed duties with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Eddy was fluent in Arabic, having been born in Lebanon in a missionary family. He was released from active duty as a colonel in August 1944 to accept an appointment as U.S. Minister to Saudi Arabia, where he served until July 1946. He died on 3 May 1962 in Lebanon at the age of 66 while serving as a consultant for the Arabian American Oil Company and was buried in Lebanon.

Headquarters and Service Company was billeted at Springtown Camp, as was Company B, which was assigned to guard the repair facilities. Company C, which guarded the Quonset storage ammunition dump at Fincairn Glen (five miles outside 'Derry), was billeted on the grounds of an old estate called "Beech Hill." Company A guarded the Naval Field Hospital at nearby Creevagh, a couple of strategically located radio stations, and a major supply depot at Lisahally. Those Marines were billeted in Quonset huts on the grounds of "Lisahally House," an estate on the River Foyle. The Marines were needed in Londonderry not only to protect the naval base from sabotage from German units which might have been landed by submarine, but also from local infiltrators. The Irish Free State (Eire), just across the border from Ulster, maintained its neutrality throughout the war. With German and Japanese embassies in full operation in Dublin, there was the fear of sabotage attempts against Allied installations, prepared with the cooperation of militant elements of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). There were no IRA-supported sabotage attempts, however, and history reveals that the number of voluntary Irish enlistments in the British Army from Eire equalled the number from Ulster, where the draft was in effect.

An interesting incident took place during this period, which underscored the high degree of cooperation between the two Irish governments. A New Zealand bomber crash-landed in Eire and its crew expected to be interned for the duration of the war by the Irish Free State. However, with the unofficial blessing of the Irish Government, the RAF with the assistance of a detail from the Marine Barracks, dismantled the plane and removed it and its crew across the border.

Major James J. Dugan, the barracks adjutant, was a colorful member of the original "Irish Marines," a nickname given to the Marines serving in Londonderry. He was a red head from Boston who brought with him several members of his Boston reserve unit. He retained good rapport with the Irish and formed from the barracks drum and bugle corps a bagpipe band which became a trademark of this unit. The Marines were a welcome sight to this area, which had sent most of its young men off to war in 1939 in the British Army, and from which many never returned. Since rain falls on average 240 days out of the year in this area, Marines learned quickly to do without clear days. They also learned to respect the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), which did a very efficient job of maintaining law and order in this historic city of 48,000 people. The Marines on shore patrol duty, commanded by Captain William P. Alston, established a good working relationship with the RUC, and also with Superintendent of Police Tom Collins, from Londonderry's neighboring County Donegal, who be came a frequent guest at battalion social events.

Just as the "Irish" battalion arrived in Londonderry, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was relieved in Iceland by an Army unit and returned to the 2d Marine Division at Camp Pendleton. A continuing Marine presence was maintained in Iceland, however, with the organization of a Marine Barracks stationed at the Fleet Air Base in Reykjavik. This 100-man unit was initially commanded by Major Hewin O. Hammond. It would remain in Iceland until 22 October 1945, when it was disbanded. Meanwhile, in London, Naval Forces Europe welcomed its commander (ComNavEu) on 17 March 1942, with the arrival of Admiral Harold R. Stark. He had been Chief of Naval Operations until he was replaced by Admiral Ernest J. King after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Marine Detachment, which had been on duty in London at the same location in Grosvenor Square since June 1941, became also a naval security detachment. However, it retained its American Embassy designation and continued to perform security duties for the Embassy. Additional duties included: providing security for the naval headquarters; supplying orderlies for several flag officers, including ComNavEu; and augmenting the motorcycle courier service linking the various military headquarters in London. In their capacities as special naval observers, the detachment commander, Major Jordan, and his executive officer, Captain John Hill, continued to visit various Allied commands throughout the United Kingdom.

Colonel Franklin A. Hart, who had been on duty in London since June as an assistant naval attache at the American Embassy, now joined the ComNavEu staff as Chief of Naval Planning Section. Hart and Marine aviator Lieutenant Colonel Harold D. Campbell were assigned to duties as liaison officers to the Commander of Combined Operations, Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. These duties involved them in the planning and preparation for the combined British-Canadian forces' amphibious raid on 19 August 1942 at Dieppe, on the northeastern coast of France. They both observed this operation from the deck of a British destroyer, HMS Fernie. The Dieppe landing was originally scheduled for 3 July. The elaborate amphibious raid was to involve more than 6,000 troops, mostly Canadian, and more than 250 ships. Royal Marine commandos, American rangers, and Free French soldiers also were to participate. Had it taken place on the scheduled date, three U.S. Marines would have participated as part of a Royal Marine commando, landing from HMS Locust. Captain Roy Batterton, Sergeant Robert R. Ryan, and Corporal Paul E. Cramer were the three Marines who boarded the ship at Portsmouth, England, in preparation for a landing that was then postponed because of bad weather. After further postponements, their participation was cancelled, and they went on to complete their commando training on 30 July, and prepared for reassignment in the States. In retrospect, we know that these Marines were fortunate to have missed out on the Dieppe raid, because it was a fiasco.

Planned as a surprise attack without benefit of air or naval gun fire preparation, it was designed to test Allied ability to assault and seize a port, to test new types of assault craft and equipment, and to continue to keep the Germans on edge as to Allied plans for a cross-channel invasion. However, tactical surprise was not achieved and the landing party was overwhelmed. After five hours of heavy fighting, the landing force withdrew, suffering a loss of 3,648 men killed, wounded, missing, or captured. Possibly the best that can be said of this costly lesson is that it was a part of the price paid to help to ensure the highly successful landing at Normandy on 6 June 1944. There, unlike Dieppe, there would be no attempt to seize a heavily defended port, and the assault would be made in daylight, preceded and covered by the heaviest naval and air bombardment that could be devised.

Shortly after the Dieppe operation, Colonels Hart and Campbell returned to Washington, where they were able to draw upon their experiences in planning for amphibious operations in the Pacific. Hart was succeeded by Marine Colonel William T. Clement in October 1942. Clement, who had narrowly escaped capture by the Japanese at Corregidor, was assigned to the Intelligence Division of ComNavEu to work on naval planning for the cross-channel invasion of Europe. Admiral Stark, in a letter of 13 July 1943 to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, praised Colonel Clement for his work in setting up the Intelligence Section of ComNavEu.

|