| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

A DIFFERENT WAR: Marines in Europe and North Africa by Lieutenant Colonel Harry W. Edwards, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) Assignment to London (continued) During May and June 1941, Major Gerald C. Thomas and Captain James Roosevelt followed one of the most interesting itineraries of any Marine in the European Theater. On a special mission for President Roosevelt, they flew from India to Basra, Iraq, along with Brigadier William Slim of the British Army, arriving at a hotel that was filled with wounded soldiers. They flew from there on a British Sunderland flying boat to Suez, and on by car to Cairo, where they met two more Marine observers, Farrell and Captain Parmalee. After a briefing by the staff of Air Vice Marshal Arthur Tedder (later General Eisenhower's top deputy in Europe), they had a visit with General Sir Archibald Wavell, Middle East commander. Thereafter, they obtained requested transportation to Crete to deliver a message to King George, who had been driven from his throne in Greece by the Germans. Despite dire warnings of danger, they flew in a British flying boat to Crete, where they landed in the midst of a German air raid. Nevertheless, they completed their mission, which was to deliver the letter from President Roosevelt to King George, and then departed for Alexandria, Egypt. From Cairo they flew to Jerusalem for visits with King Peter of Yugoslavia; the High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir John McMichael; and Abdul, the Regent of Iraq. They were nearly killed here during a strafing attack by German fighters. They had only sandbags for protection, since there were no dugouts to hide in because of the high water table in the area. By the time they returned to Cairo, the Germans had already invaded Crete and seized the island with heavy losses for the British defense force. Returning to Cairo, they visited General Charles de Gaulle at his Free French Headquarters, then in Cairo, before leaving (along with Parmalee and Farrell) on a flying boat for Lisbon. Then-Captain Mountbatten also was a passenger on that flight. He had earlier lost his destroyer division in the battle of Greece, and he told them that his nephew, Prince Philip, was also a survivor of that action. At the end of that memorable trip, Major Thomas reported to the Commandant of the Marine Corps and requested to be returned to duty with troops. General Franklin A. Hart, USMC By the time Colonel Franklin A. Hart arrived for duty in London in June 1941, he already had a distinguished record of Marine Corps service.

A student at Auburn University, class of 1915, Hart was a top athlete in football, track, and soccer. He served as a Marine officer in France in World War I, and later in the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, followed by a tour of sea duty and another of shore duty in Hawaii. As a Special Naval Observer in England during World War II, he participated in the Dieppe operation in July 1942 and remained in England until October on the ComNavEu staff. In June 1943 he commanded the 24th Marines in the Marshall Islands and at both Saipan and Tinian, from which operations he earned the Navy Cross and the Legion of Merit. As assistant division commander of the 4th Marine Division on Iwo Jima, he received a Bronze Star Medal. Subsequent duty assignments included: Director, Division of Reserve, and Director, Public Information, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps; and Commanding General, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island. After his last command as Commandant, Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Lieutenant General Hart retired in 1954 and was promoted to general on the retired list. He died on 22 June 1967. The muster rolls of the Marine Detachment in London frequently included the names of "visiting" Marines. The number of visitors each month varied, as did their assignments and missions. In this category, OSS Marines were a most unusual group, mostly reservists recruited because they possessed highly specialized skills needed to carry out the organization's intelligence mission. The OSS was established on 13 June 1942 as a successor to the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI). Its director was Army Reserve Colonel William J. Donovan, a World War I hero and recipient of the Medal of Honor, whose reputation for fearlessness earned him the nick name of "Wild Bill!" OSS was a strategic intelligence organization which functioned outside the military services to carry out missions assigned by the chiefs of the armed services.

In addition to its civilian personnel, OSS had the authority to recruit military personnel from all services. Marine officers assigned to this work were given a specialty of MSS: Miscellaneous Strategic Services. More than 35 Marine officers and a considerable number of enlisted Marines were assigned to duty with the OSS in Africa and Europe during the war. Their duties were so highly secret that even their award citations were classified and remained so until after the war. Captain Peter J. Ortiz, for example, was twice awarded the Navy Cross, but these citations were not immediately published. The Marine Corps personnel in OSS made significant contributions to the Allied war effort in Europe and throughout the world.

In October 1942, two COI/OSS Marines were stationed at the American Legation in Tangiers, Morocco, a key listening post in Africa for the U.S. at the time. They were Lieutenant Colonel William A. Eddy and Second Lieutenant Franklin Holcomb. Eddy was born in Lebanon of American missionary parents and was fluent in Arabic. He had earned a Navy Cross and two Silver Star Medals for combat action with the 6th Marines in World War I. Holcomb was the only son of the Marine Corps Commandant, General Holcomb. Both officers were designated assistant naval attaches for air and would play a prominent role in relations with the Vichy French, and in providing valuable intelligence for Allied landings in Africa. Robert D. Murphy, counselor of the American Embassy in Vichy, once commented that "no American knew more about Arabs or power politics in Africa than Colonel Eddy." In January 1943 they were joined in Tangier by Captain Ortiz. He was an American citizen but had served in the French Foreign Legion early in World War Il. Thus, he was well acquainted with the area.

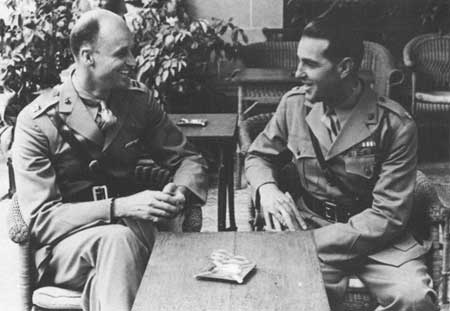

Marine Reserve Lieutenant Otto Weber also received an unusual assignment. A petroleum specialist as a civilian, he was ordered, under the auspices of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), to report for duty in Cairo. From there he went to Asmara, Eritrea, where he stayed for several months, and finally he returned to Cairo and served as an intelligence officer with the Army Forces in the Middle East. Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, USMC One of the most decorated Marine officers of World War II, Colonel Peter Ortiz served in both Africa and Europe throughout the war, as a member of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Although born in the U.S., he was educated in France and began his military service in 1932 at the age of 19 with the French Foreign Legion. He was wounded in action and imprisoned by the Germans in 1940. After his escape, he made his way to the U.S. and joined the Marines. As a result of his training and experience, he was awarded a commission, and a special duty assignment as an assistant naval attache in Tangier, Morocco. Once again, Ortiz was wounded while performing combat intelligence work in preparation for Allied landings in North Africa. In 1943, as a member of the OSS, he was dropped by parachute into France to aid the Resistance, and assisted in the rescue of four downed RAF pilots. He was recaptured by the Germans in 1944 and spent the remainder of the war as a POW. Ortiz's decorations included two Navy Crosses, the Legion of Merit, the Order of the British Empire, and five Croix de Guerre. He also was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French. Upon return to civilian life, Ortiz became involved in the film industry. At the same time, at least two Hollywood films were made based upon his personal exploits. He died on 16 May 1988 at the age of 75.

As a result of the lend-lease to the Royal Navy of 50 overage destroyers early in the war, the British made available to the United States bases on various islands in the Atlantic. Marine units were posted at several of these naval bases, where they remained throughout the war. They included: Marine Barracks in Bermuda, Trinidad, and Argentia, Newfoundland, and Marine detachments on Grand Cayman and Antigua islands and in the Bahamas. As a result of the lend-lease to the Royal Navy of 50 overage destroyers early in the war, the British made available to the United States bases on various islands in the Atlantic. Marine units were posted at several of these naval bases, where they remained throughout the war. They included: Marine Barracks in Bermuda, Trinidad, and Argentia, Newfoundland, and Marine detachments on Grand Cayman and Antigua islands and in the Bahamas.

|