|

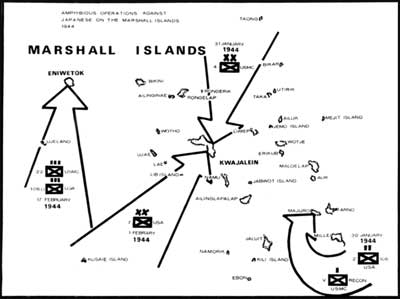

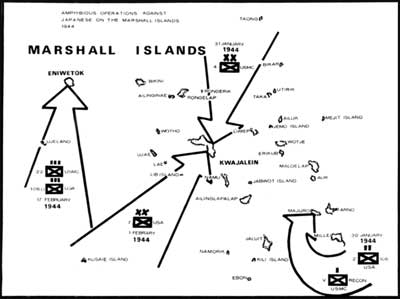

BREAKING THE OUTER RING: Marine Landings in the Marshall Islands

by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret)

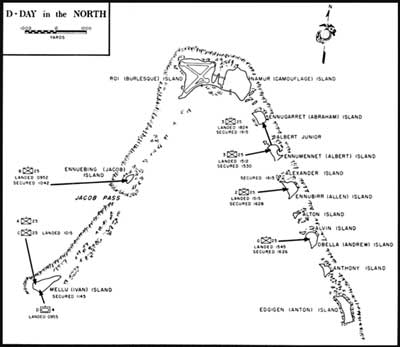

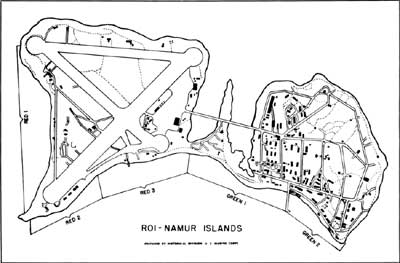

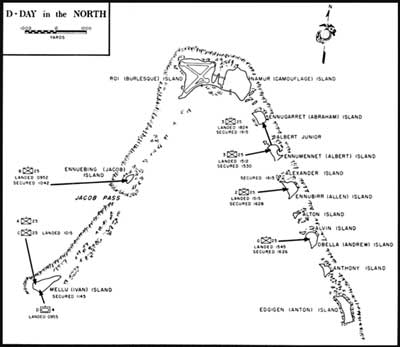

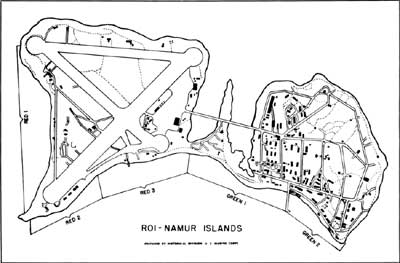

The Marine Attack: Roi-Namur

As the amphibian tractors sought to form up in

organized attack waves, a series of problems arose. There was a

continuation of the rough weather and radio communications difficulties

of the day before; the amtrac crews had not previously practiced with

the assault units; the control ship turned out to have been assigned

firing missions as well as wave control and left its control station

(followed by some stray amtracs); the attack commander was reduced to

racing around in a small ship and shouting instructions through a

megaphone. As a result, W-hour, the hour for attack, had to be postponed

from 1000 to 1100.

Meanwhile the men in the amtracs (and some in hastily

scrounged up LCVPs [landing craft, vehicle or personnel]) were watching

the awe-inspiring sight of the furious bombardment. Overhead, for the

first time in the Pacific War, two Marines were in airplanes to act as

naval gunfire controllers who would cut off the shelling when the troops

approached the beach. Brigadier General William W. Buchanan later

recalled how one of them "on one of his passes found one of the trenches

on the north side of Namur filled with a number of troops crouching down

in the trench. So he asked the pilot to go in on a strafing attack, and

then as they came over he was going to continue raking them with the

machine guns. He did this to such a point that, after they got back to

the ship, it was determined that in his [the spotter's] enthusiasm he

practically shot off the tail end!"

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

Down in the lagoon the signal finally came to the

assault waves, "Go on in!" The two lead battalions of the 23d Marines

headed for Roi, with the two lead battalions of the 24th Marines

churning towards Namur. The memories of this run-in were burned forever

into the mind of young Second Lieutenant John C. Chapin, leading his

platoon in the first wave:

By now everything was all mixed up, with our assault

wave all entangled with the armored tractors ahead of us. I ordered my

driver to maneuver around them. Slowly we inched past, as their 37mm

guns and .50-cal. machine guns flamed. The beach lay right before us.

However, it was shrouded in such a pall of dust and smoke from our

bombardment that we could see very little of it. As a result, we were

unable to tell which section we were approaching (after all our hours of

careful planning, based on hitting the beach at one exact spot!) I

turned to talk to my platoon sergeant, who was manning the machine gun

right beside me. He was slumped over—the whole right side of his

head disintegrated into a mass of gore. Up to now, the entire operation

had seemed almost like a movie, or like one of the innumerable practice

landings we'd made.

Now one of my men lay in a welter of blood beside me,

and the reality of it smashed into my consciousness.

|

|

Col

Franklin A. Hart, commander of the 24th Marines, briefs his staff on the

operation plan for the invasion of Roi-Namur. To his left is his

regimental executive officer, LtCol Homer L. Litzenberg, Jr. Both would

retire as general officers. Department of Defense Photo (USMC

70490)

|

The landing then became a chaotic jumble of rapid

events for that officer and his men. There was a grinding crash to their

right, and looking over they saw an LVT collide at the water's edge with

an armored tractor, climb on its side and hang there, crazily atilt.

Simultaneously, there was a grating sound under their tractor as they

hit the beach. Keeping low, the men slid over the side of the tractor

and dove for cover, for their LVT was a perfect target sitting there on

the sand. The lieutenant was the last one to drop to the deck, and as he

sprawled on the sand, the amtrac ground its way backwards into the

ocean.

Now the lieutenant faced his first combat in a

situation that characterized all the landing beaches. His intensive

training stood him in good stead as he took stock of the situation.

Being in the first scattered group of tractors ashore, his men had no

contact yet with any other unit, so the Japanese were on both sides of

them—as well as in front. One glance told him that they had landed

on the west side of Namur, 300 yards to the right of the spit of land

that their company had for its objective. The long hours of studying

maps and aerial photographs had proved their worth. The lieutenant's

account continued:

My immediate task was to reorganize my platoon, for

it was scattered along the beach. The noise, smoke, and choking pall of

burnt powder further complicated things. I turned to my sergeant guide,

as we lay there in the sand, and asked him where his men were. He

started to point and right before my eyes his hand dissolved into a

bloody stump. He rolled over, screaming "Sailor! Sailor!" (This was our

code name for a corpsman. Bitter past experiences of the Marines had

shown that the Japs delighted in calling "corpsman" themselves, and then

shooting anyone who showed himself.) Soon our corpsman crawled over, and

started to give the sergeant first aid, so I turned my attention to more

pressing matters.

As yet the officer hadn't seen a single Japanese,

even though he was in the midst of them. But now one of the men next to

him gasped, "They're in there!," pointing to a slit trench four feet

away; the Marine raised himself up to a crouching position and hurled

his bayonetted rifle like a javelin into the slit trench. There was

heavy enemy fire coming at the platoon, but it was almost impossible to

determine its source. Ten feet in front of the Marines, however, the

Japanese had dug a series of trenches running the length of the beach.

Tied in with these trenches were scores of machine gun positions and

foxholes, mutually supporting each other, all camouflaged so that they

were invisible until a Marine was right on top of them. Accordingly, as

soon as the men of the platoon would locate an emplacement, they would

deluge it with hand grenades, and then work on the next one. The

lieutenant's next experience was almost his last:

At one point in this swirling maelstrom of action I

was kneeling behind a palm tree stump with my carbine on the deck, as I

fished for a fresh clip of bullets in my belt. Something made me look up

and there, not ten feet away, was a Jap charging me with his bayonet. My

hands were empty. I was helpless. The thought that "this is it" flashed

through my brain! Then shots chattered from all sides of me. My men hit

the running Jap in a dozen places. He fell dead three feet from me.

Shortly after this, the squad with the Marine officer

was working on another Japanese emplacement. He pulled the pin from one

of his grenades, let the handle fly off, and started counting to three.

(The grenade's fuse was timed to give a man about five seconds before it

exploded.) In the middle of his count, a Japanese started shooting at

him from the flank. Instinctively he turned to look for the enemy. Then

something in his mind clicked, "And what about that live grenade in your

hand?" Without looking, he threw it and dove for the deck. It went off

in mid-air and the fragments spattered all around him . . . .

|

Naval Support

The infantry assault units in the Marshalls

operations were carried by an incredible array of ships designed to

perform very specialized functions. Also included were converted

destroyers. The amphibian tractors carried the invading Marines in to

the beaches, supplemented by the older ramped landing craft. Added to

these were a jumble of acronyms: LCT, LST, LSM, etc., for infantry,

rockets, tanks, and trucks.

No landings would have been successful, however,

without the crucial support of naval gunfire and aerial bombardment. The

fast task force that roamed the Pacific and the support groups which

stood off the island objectives were visual proof of the deadly striking

power that had been reborn in the U.S. Navy in the two years since the

debacle at Pearl Harbor. Nearly all the old, slow battleships which had

lain shattered in the mud were back in action, and now were joined by

brand new, fast counterparts, and the familiar old peacetime carriers

were now supplemented by a steady flow of new fleet carriers and the

innovation of smaller escort carriers.

This is the roll call of the ships which poured in

their fire before and during the landings:

Battleships: Tennessee (BB 13),

Colorado (BB 45), Maryland (BB 46), Pennsylvania

(BB 38), Idaho (BB 42), New Mexico (BB 40), and

Mississippi (BB 41).

Heavy Cruisers: Louisville (CA 28),

Indianapolis (CA 35), Portland (CA 33), Minneapolis

(CA 36), San Francisco (CA 38), and New Orleans (CA

32).

Light Cruisers: Santa Fe (CL 60),

Mobile (CL 63), AND Biloxi (CL 80).

Carriers: Saratoga (CV 3), Princeton

(CVL 23), Langley (CVL 28), Enterprise (CV 6),

Yorktown (CV 10), Belleau Wood (CVL 24), Intrepid

(CV 11), Essex (CV 9), Cabot (CVL 27), Cowpens (CVL

25), Monterey (CVL 26), and Bunker Hill (CV 17), plus six

escort carriers.

Destroyers: The Kwajalein Atoll landings had 40 in

direct support.

|

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

Groups of Marines were forming now under their own

initiative, and beginning to work their way slowly inland. It was nearly

impossible to keep tight control of the platoon under these conditions,

but the lieutenant was moving with them, trying to get them coordinated

as best he could, when suddenly he dropped to the ground, stunned. He

recalled:

My first reaction was that someone had hit my right

cheek with a baseball bat. With the shock, instinct made me cover my

right eye with my hand. Then I realized I'd been hit. Searing my mind

came the question, "When I take my hand away, will I be able to see?"

Slowly I lowered my arm and opened my eye. I could see! Relief flooded

through me. The wound was on my cheek bone, just below the eye, and it

was bleeding profusely, so I lay there and broke out my first aid

packet. After shaking sulfa powder into the wound rather awkwardly, I

bandaged my right eye and cheekbone as best I could. The bullet had gone

completely through my helmet just above my right ear, and left a jagged,

gaping hole in the steel. My left eye was still functioning all right,

however, so after a drink from my canteen, I started forward again.

A little later I encountered another lieutenant from

our company, Jack Powers. He had been hit in the stomach, but was still

fighting. Crouching behind a concrete wall, he showed me a pillbox about

25 feet away that was full of Japs who were still very much alive and

full of fight. This strong point commanded the whole area around us and

was holding up our advance very effectively. It was about 50 feet long

and 15 feet wide, constructed of double rows of sand-filled oil drums.

Grabbing the nearest men, we explained our plan of attack and went to

work. With a couple of automatic riflemen, Jack covered the rear

entrance with fire. Taking another man and a high-explosive bangalore

torpedo, I crawled around to the front and observed for a few minutes.

Then we inched our way up to the slit that served as a front entrance,

and I threw a grenade in to keep down any Jap who might be inclined to

poke a rifle out in our faces.

Next we lighted the fuse on the bangalore, jammed it

inside the pillbox, and scrambled for shelter. The fuse was very short,

we knew, and we barely had tumbled into a nearby shell hole when we were

overwhelmed by the blast of the bangalore. Dirt sprayed all over us,

billowing acrid smoke blinded us, and the numbing concussion deafened

us. In a few moments we felt all right once more, and a glance told us

that we had closed that entrance permanently. We worked our way back to

where we'd left Jack Powers, and found that he'd managed to locate a

shaped charge of high explosive in the meantime. Taking this, we

repeated our job—this time blowing the rear entrance shut.

That took care of that pillbox! Jack looked like he

was in pretty bad shape, and I urged him to go get some medical

attention, but he refused and moved on alone to the next Jap pillbox

(where, I later learned, he was killed in a single-handed heroic attack

for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor).

|

|

Artillerymen unload ordnance on D-Day for the

preparatory bombardment from the neighboring islets to pound targets

before the infantry attacks on Roi-Namur. Department of Defense Photo (Army)

324729

|

All over Namur there were similar examples of

individual initiative. They were needed, for the island was covered with

dense jungle, concrete fortifications, administrative buildings, and

barracks. It was difficult to mount an armored attack under these

conditions. Meanwhile, the Japanese used them to their fullest extent

for cover and concealment. Enemy resistance and problems of maintaining

unit contact slowed the Marines' advance.

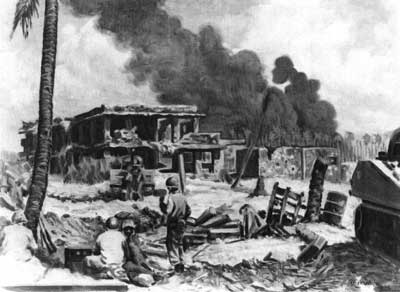

Amidst all of this, a Marine demolition team threw a

satchel charge of high explosive into a Japanese bunker which turned out

to be crammed with torpedo warheads. An enormous blast occurred. From

off shore, an officer watched as "the whole of Namur Island disappeared

from sight in a tremendous brown cloud of dust and sand raised by the

explosion." Overhead, a Marine artillery spotter felt his plane catapult

up 1,000 feet and exclaimed, "Great God Almighty! The whole damn island

has blown up!" On the beach another officer recalled that "trunks of

palm trees and chunks of concrete as large as packing crates were flying

through the air like match sticks . . . . The hole left where the

blockhouse stood was as large as a fair-sized swimming pool." The column

of smoke rose to over 1,000 feet in the air, and the explosion caused

the deaths of 20 Marines and wounded 100 others in the area.

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

Finally, at 1930, Colonel Franklin A. Hart, commander

of the 24th Marines ordered his men to dig in for the night. The troops

had come across a good portion of the island. Now they would hold the

ground gained and get ready for the morrow. One rifleman, Robert F.

Graf, later wrote about that time:

Throughout the night the fleet sent flares skyward,

lighting the islands as the flares drifted with the prevailing wind.

Ghostly flickering light was cast from the flares as they drifted along

on their parachutes. Laying in our fox hole, my buddy and I were

watching, waiting, and straining our ears trying to filter out the known

sounds.

Our foxhole in that sand was about six feet long by

two feet in depth and just about wide enough to hold the two of us.

Since I had eaten only my "D" ration since leaving the ship, I was

hungry. "D" rations were bitter-sweet chocolate bars about an inch and a

half square and were supposed to be full of energy. I removed a "K"

ration from my pack and opened it. "K" rations came in a box about the

size of a Cracker Jack box and had a waterproof coating. These rations

contained a small tin of powdered coffee or lemonade, some round hard

candies, a package of three cigarettes, and a tin about the size of a

tuna-fish can containing either cheese, hash, or eggs with a little

bacon. We dined on our rations, drank water from our canteens, and

prepared to settle in for the night . . . .

After finishing chow we elected to take two-hour

watches, one on guard while the other slept. Also we made sure we knew

where our buddies' foxholes were, both on the left and right of us. Thus

we were set up so that anyone to our front would be an enemy. Our first

night in combat had started.

|

|

Landing Vehicles, Tracked (LVTs) equipped with rocket

launchers new to the 4th Marine Division, churn towards the assault

beaches of Roi-Namur on D-Plus One. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

70694

|

Before dawn the Japanese mounted a determined

counterattack which was finally repulsed. Nevertheless, it was a tragic

night for one particular family. A 19-year-old Marine private first

class and his 44-year-old father, a corporal, had been together in the

same company back in California, but the son was hospitalized with a

minor illness and then transferred to another outfit. The father boarded

his ship prepared to sail for combat alone, but then his son was found

stowed away on it in order to be with his father. The young man was

taken off and was placed under arrest. His mother, however, telephoned

the Commandant's office in Washington and told the story of her son's

effort to be together with her husband. The charges were dropped and the

two were reunited for the trip to the Marshalls. The son was killed that

first night on Namur. The father went on fighting—alone.

Early on the afternoon of the next day, 2 February, D

plus 2, the 24th Marines finished its conquest of Namur, and the island

was declared "secured!" In the final moments of combat, however,

Lieutenant Colonel Aquilla J. Dyess, commander of the 1st Battalion, was

standing to direct the last attack of his men. A burst of machine gun

fire riddled his body, and he became the most senior officer to die in

the battle. For his superb leadership under fire he was awarded a

posthumous Medal of Honor.

|

|

Troops of the 24th Marines near the beach on Namur,

thankful for having made it safely ashore, are now awaiting the

inevitable word to resume the attack. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

70209

|

|

|

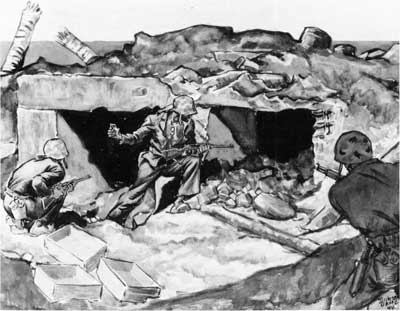

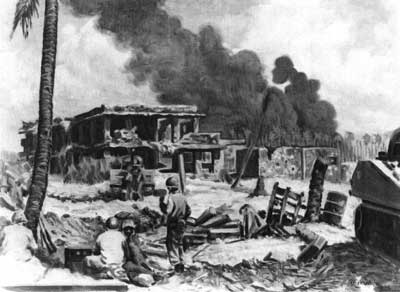

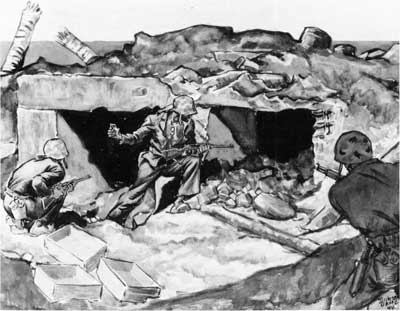

A

watercolor by combat artist LtCol Donald L. Dickson depicts members of a

Marine fire team in a close-in attack on a Japanese defensive position

on Namur. Marine Corps Art Collection

|

Across the sand spit, on Roi, it had been a different

story. This island was nearly bare, for it was mostly covered by the

airfield runways. When the 23d Marines hit the beaches on D plus 1, the

fierceness of the pre-landing bombardment prevented the Japanese

defenders from mounting a coordinated defense. Small groups of Marine

riflemen joined their regiment's attached tanks in a race across to the

far side of the island. This charging style caused considerable

confusion as to who was where. Reorganized into more coherent units, the

men made a final orderly drive to finish the job.

In spite of the rapid progress on Roi, there were

still some major enemy strongpoints which had to be dealt with. An

after-action report of the 2d Battalion described one example of this

perilous work in matter of fact terms:

[There] was a blockhouse constructed of reinforced

concrete approximately three feet thick. It had three gunports, one each

facing north, east, and west, another indication of the enemy's mistaken

assumption that the Americans would attack from the sea rather than the

lagoon shore. Two heavy hits had been made on the blockhouse, one

apparently by 14-inch or 16-inch shells and the other by an aerial bomb.

Nevertheless, the position had not been demolished . . . .

[The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Edward

J. Dillon] then ordered Company G to take the blockhouse. The company

commander first sent forward a 75mm half track, which fired five rounds

against the steel door. At this point a demolition squad came up, and

its commander volunteered to knock out the position with explosives.

While the halftrack continued to fire, infantry platoons moved up on

each flank of the installation. The demolition squad placed charges at

the ports and pushed bangalore torpedoes through a shell hole in the

roof. . . .

"Cease fire" was then ordered, and after

hand-grenades were thrown inside the door, half a squad of infantry went

into investigate. Unfortunately, the engineers of the demolition squad

had not got the word to cease fire, and had placed a shaped charge at

one of the ports while the infantry was still inside. Luckily, no one

was hurt, but as the company commander reported, "a very undignified and

hurried exit was made by all concerned." Inside were three heavy machine

guns, a quantity of ammunition, and the bodies of three Japanese.

|

|

Members of the 23d Marines on Roi turn to look in

astonishment at the black plume of the giant explosion which took many

lives in the 24th Marines on Namur. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

71921

|

|

|

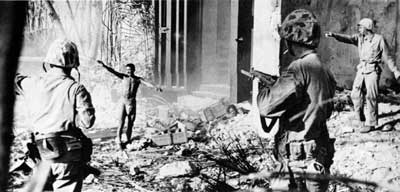

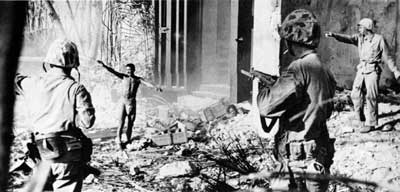

One

of the very few Japanese finally persuaded to surrender in the Roi-Namur

operation, this stripped-down soldier is well covered by suspicious

Marine riflemen as he leaves his hiding place in a massive but

shell-shattered blockhouse. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

70241

|

Many Japanese had to be flushed out of or blown up in

the airfield's drainage ditches and culverts, but by 1800 that day, D

plus 1, Roi had been secured. ("Secured" seemed a somewhat flexible term

when the first service of Mass, held the next day, was interrupted by

Japanese shots.) By 6 February, however, the ground elements of a Marine

aircraft wing were ensconced at the airfield, preparing for the arrival

of their planes in five more days. For the entire remainder of the war

these planes pounded the by-passed atolls with such power that the

Japanese on them were eliminated from any further role in the war.

(There was one surprise Japanese air raid on Roi, staged from the

Mariana Islands, on 12 February. This caused a number of casualties and

major damage to material.)

The repair of the airfield and its quick return to

action was a tribute to the skills of both the 20th Marines, an engineer

regiment, and the 109th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees). This

achievement was one more illustration of the vital role played by a

dizzying list of units that supported the assault rifle battalions.

Besides the vast armada of naval planes, ships, and landing craft, there

were Navy chaplains and corpsmen (two specialties which are always

Navy). In addition to the Marine air, artillery, and engineer units,

there were the tanks, heavy weapons, motor transport, quartermaster,

signals, and headquarters supporting units. An amphibious operation, to

be successful, must be a finely tuned, highly trained juggernaut that

depends on all its parts working smoothly together and this was clearly

demonstrated in the Marshalls.

|

|

Marine tanks and infantry worked effectively together

when the terrain permitted. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

70203

|

The conquest of Roi-Namur had been a relatively easy

operation when compared to some of the other Marine campaigns in the

Pacific. (At Tarawa, for example, more than 3,300 men had been killed or

wounded in 76 hours.) The 4th Division's victory came at a cost of 313

Marines and corpsmen killed and 502 wounded. By contrast, the defeated

Japanese garrison numbered an estimated 3,563—with all but a

handful of them now dead.

Two more tasks remained for the 4th Division; the

first was mopping up the rest of the islets in the northern two-thirds

of the atoll. The 25th Marines, which had supported the attacks of the

23d and 24th, took off on a series of island-hopping trips on board

their LVTs. The regiment checked out more of the exotically named islets

such as Boggerlapp, Marsugalt, Gegibu, Oniotto, and Eru. The 25th found

no resistance and by D plus 7 it had covered all 50 of the islets that

were its objectives. This assignment was a total change from what the

regiment had experienced around Roi-Namur. One writer, Carl W. Proehl,

described the expedition this way:

|

|

This

watercolor by LtCol Donald L. Dickson, USMCR, portrays Marines reviving

themselves and taking it easy after the fighting near blockhouse

skeleton.

|

|

|

The

once heavily overgrown terrain of Namur was almost completely denuded at

the end of the battle by the combination of naval gunfire and

bombing. National Archives Photo 127-N-72407

|

It was on this junket that the men of the 25th got to

know the Marshall Island natives, for it was these Marines who freed

them from Japanese domination. On many islets, bivouacking overnight,

the natives and Marines got together and sang hymns; the Marshall

Islanders had been Christianized many years before, and missionaries had

taught them such songs as "Onward Christian Soldiers." K rations and

cigarettes also made a big hit with them. And more than one Marine

sentry, walking post in front of a native camp, took up the islander's

dress and wore only a loin cloth—usually a towel from a Los Angeles

hotel.

The final task that remained for the division was a

miserable one. Roi and Namur were littered with dead Japanese; the

stench was overpowering as their bodies putrefied in the blazing

tropical sun. All hands, officers and enlisted, were put to work day and

night on burial details. "Hey, I just finished two days of brutal

combat! We don't have any gloves or equipment for this!"—"Too bad,

just start doing it anyway!" Health conditions were so bad that 1,500

men in the division were suffering from dysentery when the troops

finally reboarded transports for the journey back to their rear base at

Maui in the Hawaiian Islands.

|