| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

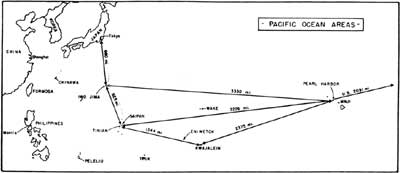

BREAKING THE OUTER RING: Marine Landings in the Marshall Islands by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret) Planning the Attack In May 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff decided to seize them. This difficult assignment fell to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz who bore the impressive titles of Commander in Chief, Pacific, and Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas (CinCPac/CinCPOA), based at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. He turned to four very capable men who would carry out the actual operation: three admirals who were experts in amphibious landings, fast carrier strikes, and shore bombardment, and Major General Holland M. Smith, who was the commanding general of the Marines' V Amphibious Corps and now also would be Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops. It was he who would command the troops once they got ashore. Original cautious plans for steppingstone attacks starting in the eastern Marshalls were modified, and the daring decision was made to knife through the edges and strike directly at Kwajalein Atoll in the heart of Marshalls' cluster of 32 atolls, more than 1,000 islands, and 867 reefs. Kwajalein is the largest atoll in the world, 60 miles long and 20 miles wide, a semi-enclosed series of 80 reefs and islets around a huge lagoon of some 800 square miles. Located 620 miles northwest of Tarawa and 2,415 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor, its capture would have far-reaching strategic significance in that it would break the outer ring of Japanese Pacific defense lines. Within the atoll itself there were two objectives: Roi and Namur, a pair of connected islands shaped like weights on a four-mile barbell in the north end, and crescent-shaped Kwajalein Island at the south end. The 4th Marine Division under Major General Harry Schmidt was to assault Roi-Namur, and the Army 7th Infantry Division under Major General Charles H. Corlett would attack Kwajalein. After these islands were taken, there was one more objective in the Marshalls: Eniwetok Atoll. This was targeted for attack some three months later by a task force comprised of the 22d Marine Regiment (called in the Corps the "22d Marines") and most of the Army's 106th Infantry Regiment. Brigadier General Thomas E. Watson, USMC, would be in command.

As a preliminary to these priority operations, the occupation of another atoll in the eastern Marshalls was planned. This objective was Majuro, which would serve as an advanced air and naval base and safeguard supply lines to Kwajalein 220 miles to the northwest. Because it was believed to be very lightly defended, only the Marine V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company and the 2d Battalion, 106th Infantry, 7th Infantry Division were assigned to capture Majuro. To support all of these thrusts there would be a massive assemblage of U.S. Navy ships: carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and an astonishingly varied array of transports and landing craft. These warships provided a maximum potential for intensive pre-invasion aerial bombing and ship-to-shore bombardment; the increased tonnage in high explosives, the lengthened duration of the softening-up process, and the pinpointing of priority enemy targets were all lessons sorely learned from the inadequate preparatory shelling which had contributed to the steep casualties of Tarawa. For the Marshalls, there were altogether 380 ships, carrying 85,000 men. With the plans in place and a very tight schedule to meet the D-day deadline, the complex task of assembling and transporting the assault troops to the target area was put in motion. Readying the Army 7th Division was the easiest part of the logistical plan; it was already in Hawaii after earlier operations at Attu and Kiska in the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. The 22d Marines, however, had to come from Samoa (where it had been on garrison duty for some 18 months), and the 4th Marine Division was still at Camp Pendleton in California, where it had recently been formed. On 13 January 1944, the division sailed from San Diego to commence the longest shore-to-shore amphibious operation in the history of warfare: 4,300 miles! Major General Holland M. Smith One of the most famous Marines of his time, General Smith was born in 1882. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1905. There followed a series of overseas assignments in the Philippines, Nicaragua, Santo Domingo, and with the Marine Brigade in France in World War I. Beginning in the early 1930s, he became increasingly focused on the development of amphibious warfare concepts. Soon after the outbreak of war with Japan in 1941, he was assigned to a crucial position, command of all Marines in the Central Pacific. As another Marine officer later described him, "He was of medium height, perhaps five feet nine or ten inches, and somewhat paunchy. His once-black hair had turned gray. His once close-trimmed mustache was somewhat scraggly. He wore steel-rimmed glasses and he smoked cigars incessantly!" There was one other feature that characterized him: a ferocious temper that earned him the nickname, "Howlin' Mad" Smith, although his close friends knew him as "Hoke."

This characteristic would usually emerge as irritation at what he felt were sub-standard performances. One famous example of this was his relief of an Army general from his command. It came when an Army division was on the line alongside two Marine divisions on Saipan in the Marianas Islands campaign following the Marshalls operation. A huge interservice uproar erupted! Less than two years later, after 41 years of active service, during which he was awarded four Distinguished Service Medals for his leadership in four successive successful amphibious operations, he retired in April 1946, as a four-star general. He died in January 1967. Life at sea soon settled down into a regular routine. All hands soon became acquainted with the rituals of alerts for "General Quarters" in the blackness of predawn, mess lines stretching along the passageways, inspections and calisthenics on the cluttered decks, the loudspeaker with its shrill whistle of a "bosun's pipe" and its "Now hear this!," fresh water hours, and classes and weapons-cleaning every day. Off duty, the men took advantage of the opportunity to sleep, play cards, stand in line for ice cream, write letters, and, of course, engage in endless speculation about the division's objective (which was originally known only by the intriguing title of "Burlesque and Camouflage"). On 21 January the transports carrying the Marines anchored in Lahaina Roads off Maui, Hawaii, and visions of shore leave raced through the minds of all the men: hula girls, surf swimming, cooling draughts in a local bar—just what was needed after the long nights in the crowded, humid troop compartments during the voyage. Over the ships' loud speakers, sad to say, came a not unexpected announcement, "There will be no liberty. . . ." After one day filled with conferences and briefings for the senior officers, the task force sailed again. Next stop: the Marshall Islands! En route, crossing the 180th Meridian, there were the traditional, colorful ceremonies in which the old salts initiated the men who had never before crossed the International Date Line into the "Domain of the Golden Dragon." On 30 January the ships threaded their way through the eastern atolls of the Marshalls, and the following morning (dawn, 31 January) they halted before their objectives, with the northern component off Roi-Namur and the southern component facing Kwajalein Island. On every transport the men crowded the ships' rails to stare at the low-lying islets which they must soon attack. The 23d, 24th, and 25th Marines were assigned to the Roi-Namur operation, and the 32d, 17th, and 184th Infantry Regiments of the Army's 7th Division were to take the Kwajalein Island objectives. Meanwhile, the small group assigned to Majuro (2d Battalion, 106th Infantry, plus the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company) had split off from the main task force and would make its own landing on 31 January. Advance intelligence estimates of minimal enemy forces proved accurate; there were no American casualties and just one Japanese officer was captured on the main islet. Three days later more than 30 U.S. ships lay at anchor in the Majuro lagoon. Forward at the main theater, an awesome pre-landing saturation bombardment, begun on 29 January, was in full swing. U.S. Navy ships moved in on Roi-Namur, with some at the unprecedented short range of 1,900 yards, and poured in their point-blank massed fire. Continuing the repeated aerial strikes which had begun weeks earlier from the carriers, waves of planes swept in low for bombing and strafing runs. Key enemy artillery and blockhouse strong points had earlier been mapped from submarine and aerial reconnaissance, and individual attention was given to the destruction of each one. The combined total of shells and bombs reached a staggering 6,000 tons. As a result of the underwater obstacles and beach mines uncovered at Tarawa, for the first time Navy underwater demolition teams had been formed for future operations. Fortunately, they found no mines at Roi Namur and were not needed at Kwajalein. Major General Harry Schmidt

The leader of the 4th Marine Division at Roi-Namur was born in 1886 and entered the Corps as a second lieutenant in 1909. By extraordinary coincidence, his first foreign duty was at Guam in the Marianas Islands, an area he would return to 33 years later under vastly different circumstances! The Philippines, Mexico, Cuba, and Nicaragua (where he was awarded a Navy Cross—second only to the Medal of Honor), interspersed with repeated stays in China, were the marks of a diverse overseas career. At home, there were staff schools, paymaster duties, and a tour as Assistant Commandant. By the end of the war, he had been decorated with three Distinguished Service Medals. Retiring in 1948 after 39 years of service, he was advanced to the four-star rank of general. He died in 1968. A contemporary described him as "a Buddha, a typical old-time Marine: he had been in China; he was regulation Old Establishment; a regular Marine." Another factor which would assist the assault troops was the configuration of the atoll. The two main objectives, at the north end and at the south, were each adjoined by islets, and these neighboring locations were to be seized on D-day, 31 January, as bases to provide close-in artillery support for the infantry landing. On either side of Roi-Namur the 14th Marines would bring in its 75mm and 105mm howitzers and dig them in to support the main landing from islets which carried the exotic names of Ennuebing, Mellu, Ennubirr, Ennumennet, and Ennugarret. As is always the case in war, there were problems. The task was assigned to the 25th Marines, and, because of communications difficulties, the different units going ashore on different islets could not coordinate their landings. Their radios went dead from drenching sea swells that swept over the gunwales of the amtracs (LVTs, landing vehicles, tracked, or amphibian tractors). Nevertheless, by nightfall, the beachheads had been secured, and, for the first time, U.S. Marines had landed on a Japanese mandate. On board the transports outside the lagoon, the men of the 23d and 24th Marines spent the afternoon of D-day transferring to LSTs (Landing Ships, Tank). That night saw a muddled picture of amphibian tractors stranded or out of gas inside the lagoon, with many others wandering in the blackout as they sought to find their own LST mother ship.

While this scramble was going on, the assault troops on board the LSTs were facing, each in his own way, the prospect of intensive combat on the following morning. One rifleman, Private First Class Robert F. Graf, remembered:

By the next morning, D plus 1, 1 February, the LSTs had moved inside the lagoon. Up before dawn, the infantrymen filed into the cavernous holds of the LSTs and clambered on-board their amphibious tractors. Graf described his equipment:

|