| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

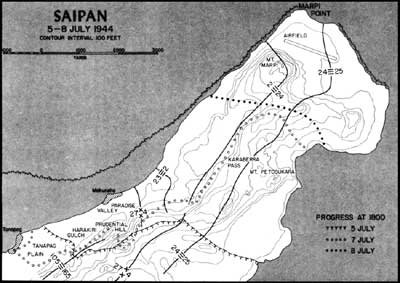

BREACHING THE MARIANAS: The Battle for Saipan by Captain John C. Chapin U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (Ret) D+20—D+23, 5—8 July Any Japanese "withdrawal" meant that some of their men were left behind in caves to fight to the death. This tactic produced again and again for the American troops the life-threatening question of whether there were civilians hidden inside who should be saved. There was a typical grim episode at this time for First Lieutenant Frederic A. Stott, in the 1st Battalion, 24th Marines:

This kind of treacherous action by the Japanese was demonstrated in a different form on the following day (D+21). Lieutenant Colonel Chambers described how he dealt summarily with it—and, by contrast how his men treated genuine civilians who had been hiding:

Once the 2d Marine Division became corps reserve, it was obvious to General Smith that the time was ripe for a banzai attack. He duly warned all units to be alert, and paid a personal visit on 6 July to General Griner, of the 27th Infantry Division, to stress the likelihood of an attack coming down the coastline on the flat ground of the Tanapag Plain. General Saito was now cornered in his sixth (and last) command post, a miserable cave in Paradise Valley north of Tanapag. The valley was constantly raked by American artillery and naval gunfire; he had left only fragmentary remnants of his troops; he was himself sick, hungry, and wounded. After giving orders for one last fanatical banzai charge, he decided to commit hara-kiri in his cave. At 10a.m. on 6 July, facing east and crying "Tenno Haika! Banzai! [Long live the Emperor! Ten thousand ages!]," he drew his own blood first with his own sword and then his adjutant shot him and Admiral Nagumo in the head with a pistol, but not before he said, "I will meet my staff in Yasakuni Shrine 3 a.m., 7 July!" This was to be the time ordered for the commencement of the final attack.

Medal of Honor Recipients

Private First Class Harold Christ Agerholm was born on 29 January 1925, in Racine, Wisconsin. "For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving with the Fourth Battalion, Tenth Marines, Second Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Saipan, Marianas Islands, 7 July 1944. When the enemy launched a fierce, determined counterattack against our positions and overran a neighboring artillery battalion, Private First Class Agerholm immediately volunteered to assist in the effort to check the hostile attack and evacuate our wounded. Locating and appropriating an abandoned ambulance jeep, he repeatedly made extremely perilous trips under heavy rifle and mortar fire and single-hand edly loaded and evacuated approximately 45 casualties, working tirelessly and with utter disregard for his own safety during a grueling period of more than 3 hours. Despite intense, persistent enemy fire, he ran out to aid two men whom he believed to be wounded Marines, but was himself mortally wounded by a Japanese sniper while carrying out his hazardous mission. Private First Class Agerholm's brilliant initiative, great personal valor and self-sacrificing efforts in the face of almost certain death reflect the highest credit upon himself and the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

Private First Class Harold Glenn Epperson was born on 14 July 1923, in Akron, Ohio. "For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving with the First Battalion, Sixth Marines, Second Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on the Island of Saipan in the Marianas, on 25 June 1944. With his machine-gun emplacement bearing the full brunt of a fanatic assault initiated by the Japanese under cover of predawn darkness, Private First Class Epperson manned his weapon with determined aggressiveness, fighting furiously in the defense of his battalion's position and maintaining a steady stream of devastating fire against rapidly infiltrating hostile troops to aid . . . in breaking the abortive attack. Suddenly a Japanese soldier, assumed to be dead, sprang up and hurled a powerful hand grenade into the emplacement. Determined to save his comrades, Private First Class Epperson unhesitatingly chose to sacrifice himself and, diving upon the deadly missile, absorbed the shattering violence of the exploding charge in his own body Stout-hearted and indomitable in the face of certain death, Private First Class Epperson fearlessly yielded his own life that his able comrades might carry on . . . . His superb valor and unfaltering devotion to duty throughout reflect the highest credit upon himself and upon the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country"

Sergeant Grant Frederick Timmerman was born on 14 February 1919, in Americus, Kansas. "For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Tank Commander serving with the Second Battalion, Sixth Marines, Second Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces on Saipan, Marianas Islands, on 8 July 1944. Advancing with his tank a few yards ahead of the infantry in support of a vigorous attack on hostile positions, Sergeant Timmerman maintained steady fire from his antiaircraft sky mount machine gun until progress was impeded by a series of enemy trenches and pillboxes. Observing a target of opportunity he immediately ordered the tank stopped and, mindful of the danger from the muzzle blast as he prepared to open fire with the 75mm, fearlessly stood up in the exposed turret and ordered the infantry to hit the deck. Quick to act as a grenade, hurled by the Japanese, was about to drop into the open turret hatch, Sergeant Timmerman unhesitatingly blocked the opening with his body holding the grenade against his chest and taking the brunt of the explosion. His exceptional valor and loyalty in saving his men at the cost of his own life reflect the highest credit upon Sergeant Timmerman and the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country." Also receiving a Medal of Honor, GySgt Robert H. McCard, 4th Tank Battalion, 4th Marine Division.

The ultimate outcome was clear to Saito: "Whether we attack, or whether we stay where we are, there is only death." The threat of a mad, all-out enemy charge was nothing new to the troops on Saipan. A rifleman recounted one such experience:

His account continued with a dramatic description of the tense waiting he endured, while he listened to the enemy "yells and screams going on for hours." The noise increased as Marine artillery and mortars, pounding in the direction of the Japanese sounds, added to the deafening din. The Marines were waiting in their foxholes with clips of ammo placed close at hand so that they could reload fast, fixing their bayonets onto their rifles, ensuring that their knives were loose in their scabbard all in anticipation of the forthcoming attacks. Listening to the screaming, all senses alert, many of the men had prayers on their lips as they waited. Unexpectedly, there was silence, a silence that signaled the enemy's advance. Then:

This was the wild chaos that General Smith predicted as the final convulsive effort of the Japanese. And it came indeed in the early morning hours of 7 July (D+22), the climactic moment of the battle for Saipan. The theoretical Japanese objective was to smash through Tanapag and Garapan and reach all the way down to Charan-Kanoa. It was a "fearful charge of flesh and fire, savage and primitive. . . . Some of the enemy were armed only with rocks or a knife mounted on a pole." The avalanche hit the 105th Infantry, dug in for the night with two battalions on the main line of resistance and the regimental headquarters behind them. However, those two forward battalions had left a 500-yard gap between them, which they planned to cover by fire. The Japanese found this gap, poured through it, and headed pell mell for the regimental headquarters of the 105th. The men of the frontline battalions fought valiantly but were unable to stop the banzai onslaught. Three artillery battalions of the 10th Marines behind the 105th were the next target. The gunners could not set their fuses fast enough, even when cut to four-tenths of a second, to stop the enemy right on top of them. So they lowered the muzzles of their 105mm howitzers and spewed ricochet fire by bouncing their shells off the foreground. Many of the other guns could not fire at all, since Army troops ahead of them were inextricably intertwined with the Japanese attackers. However, other Marines in the artillery battalions fired every type of small weapon they could find. The fire direction center of one of their battalions was almost wiped out, and the battalion commander was killed. The cane field to their front was swarming with enemy troops. The guns were overrun and the Marine artillerymen, after removing the firing locks of their guns, fell back to continue the fight as infantrymen.

The official history of the 27th Infantry Division recounts sadly the reactions of its fellow regiments when the firestorm broke on the 105th. The men of the nearby 165th Infantry chose that morning to "stand where they were and shoot Japs without any effort to move forward." By 1600 that afternoon, after finally starting to move to the relief of the shattered 105th, the 165th "was still 200 to 300 yards short" of making contact. This tardiness was unfortunately matched by "the long delay in the arrival of the 106th Infantry" to try to shore up the battered troops of the 105th. The extraordinarily bitter hand-to-hand fighting finally took the momentum out of the Japanese surge, and it was stopped at last at the CF of the 105th some 800 yards south of Tanapag. By 1800 most of the ground lost had been regained. It had been a ghastly day. The 105th Infantry's two battalions had suffered a shocking 918 casualties while killing 2,295 Japanese. One of the Marine artillery battalions had 127 casualties, but had accounted for 322 of the enemy A final count of the Japanese dead reached the staggering total of 4,311, some due to previous shell-fire, but the vast majority killed in the banzai charge. Amidst the carnage, there had been countless acts of bravery. Two that were recognized by later awards of the Army Medal of Honor were the leadership and "resistance to the death" of Army Lieutenant Colonel William J. O'Brien, commander of a battalion of the 105th Infantry, and one of his squad leaders, Sergeant Thomas A. Baker. Three Marines each "gallantly gave his life in the service of his country" and were posthumously awarded the Navy Medal of Honor. They were Private First Class Harold C. Agerholm, Private First Class Harold G. Epperson, and Sergeant Grant F. Timmerman. The 3d Battalion, 10th Marines, which had fought so tenaciously in the banzai assault, received the Navy Unit Commendation. Four years later, the 105th Infantry and its attached tank battalion were awarded the Army Distinguished Unit Citation. While attention centered on the bloody battle on the coast, the 23d Marines was attacking a strong Japanese force well protected by caves in a cliff inland. The key to their elimination was an ingenious improvisation. In order to provide fire support, truck-mounted rocket launchers were lowered over the cliff by chains attached to tanks. Once down at the base, their fire, supplemented by that of rocket gunboats off shore, snuffed out the enemy resistance. The next day, D+23, 8 July, saw the beginning of the end. The Japanese had spent the last of their unit manpower in the banzai charge; now it was time for the final American mop-up. LVTs rescued men of the 105th Infantry who had waded out from the shore to the reef to escape the Japanese. Holland Smith then moved most of the 27th Infantry Division into reserve, and put the 2d Marine Division back on the line of attack, with the 105th Infantry attached. Together with the 4th Marine Division, they swept north towards the end of the island. Along the coast there were bizarre spectacles that presaged a macabre ending to the campaign. The official Marine history pictured the scene:

|