| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

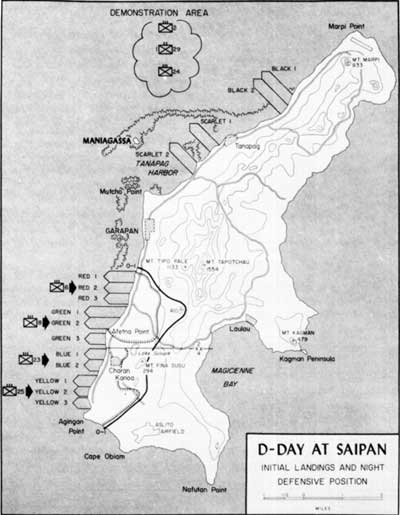

BREACHING THE MARIANAS: The Battle for Saipan by Captain John C. Chapin U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (Ret) It was to be a brutal day At first light on 15 June 1944, the Navy fire support ships of the task force lying off Saipan Island increased their previous days' preparatory fires involving all calibers of weapons. At 0542, Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner ordered, "Land the landing force." Around 0700, the landing ships, tank (LSTs) moved to within approximately 1,250 yards behind the line of departure. Troops in the LSTs began debarking from them in landing vehicles, tracked (LVTs). Control vessels containing Navy and Marine personnel with their radio gear took their positions displaying flags indicating which beach approaches they controlled. Admiral Turner delayed H-hour from 0830 to 0840 to give the "boat waves" additional time to get into position. Then the first wave headed full speed toward the beaches. The Japanese waited patiently, ready to make the assault units pay a heavy price. The first assault wave contained armored amphibian tractors (LVT[A]s) with their 75mm guns firing rapidly. They were accompanied by light gunboats firing 4.5-inch rockets, 20mm guns, and 40mm guns. The LVTs could negotiate the reef, but the rest could not and were forced to turn back until a passageway through the reef could be discovered.

Earlier, at 0600, further north, a feint landing was conducted off Tanapag harbor by part of the 2d Marines in conjunction with the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, and the 24th Marines. The Japanese were not really fooled and did not rush reinforcements to that area, but it did tie up at least one enemy regiment. When the LVT(A)s and troop-carrying LVTs reached the reef, it seemed to explode. In every direction and in the water beyond on the way to the beaches, great geysers of water rose with artillery and mortar shells exploding. Small-arms fire, rifles, and machine guns joined the mounting crescendo. The LVTs ground ashore. Confusion on the beaches, particularly in the 2d Marine Division area, was compounded by the strength of a northerly current flow which caused the assault battalions of the 6th and 8th Marines to land about 400 yards too far north. This caused a gap to widen between the 2d and 4th Marine Divisions. As Colonel Robert E. Hogaboom, the operations officer of the Expeditionary Troops commented: "The opposition consisted primarily of artillery and mortar fire from weapons placed in well-deployed positions and previously registered to cover the beach areas, as well as fire from small arms, automatic weapons, and anti-boat guns sited to cover the approaches to and the immediate landing beaches."

As a result, five of the 2d Marine Division assault unit commanders were soon wounded in the two battalions of the 6th Marines (on the far left), and in the two battalions of the 8th Marines. With Afetan Point in the middle spitting deadly enfilade fire to the left and to the right, the next units across the gap were two battalions of the 23d Marines and, finally, on the far right, two battalions of the 25th Marines. Although the original plan had been for the assault troops to ride their LVTs all the way to the O-1 (first objective) line, the deluge of Japanese fire and natural obstacles prevented this. A few units in the center of the 4th Division made it, but fierce enemy resistance pinned down the right and left flanks. The two divisions were unable to make direct contact. A first lieutenant in the 3d Battalion, 24th Marines, John C. Chapin, later remembered vividly the extra ordinary scene on the beach when he came ashore on D-Day:

When his company moved in land a short distance, it quickly experienced the frightening precision of the pre-registered Japanese artillery fire:

That night the lieutenant and his runner shared a shallow foxhole and split the watches between them. Death came close:

All the assault regiments were taking casualties from the constant shelling that was zeroed in by spotters on the high ground inland. Supplies and reinforcing units piled up in confusion on the landing beaches. Snipers were everywhere. Supporting waves experienced the same deadly enemy fire on their way to the beach. Some LVTs lost their direction, some received direct hits, and others were flipped on their sides by waves or enemy fire spilling their equipment and personnel onto the reef. Casualties in both divisions mounted rapidly. Evacuating them to the ships was extremely dangerous and difficult. Medical aid stations set up ashore were under sporadic enemy fire.

As the Marine artillery also landed in the late afternoon of D-Day and began firing in support of the infantry, it received deadly accurate counter-battery fire from the Japanese. The commander of the 4th Division, Major General Harry Schmidt, came ashore at 1930 and later recalled, "Needless to say, the command post during that time did not function very well. It was the hottest spot I was in during the war...."

Capt Carl W. Hoffman, executive officer of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, endured a mortar barrage that had uncanny timing and precision:

Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith

Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, one of the most famous Marines of World War II, was born in 1882. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1905. There followed a series of overseas assignments in the Philippines, Nicaragua, Santo Domingo, and with the Marine Brigade in France in World War I. Beginning in the early 1930s, he became increasingly focused on the development of amphibious warfare concepts. Soon after the outbreak of war with Japan in 1941, he came to a crucial position, command of all Marines in the Central Pacific. As another Marine officer later described him, "He was of medium height, perhaps five feet nine or ten inches, and somewhat paunchy. His once-black hair had turned gray. His once close-trimmed mustache was somewhat scraggly. He wore steel-rimmed glasses and he smoked cigars incessantly." There was one other feature that characterized him: a ferocious temper that earned him the nickname "Howlin' Mad" Smith, although his close friends knew him as "Hoke." This characteristic would usually emerge as irritation at what he felt were substandard performances. One famous example of this was his relief of an Army general on Saipan. A huge interservice uproar erupted! Less than two years later, after 41 years of active service, during which he was awarded four Distinguished Service Medals for his leadership in four successive successful amphibious operations, he retired in April 1946, as a four-star general. He died in January 1967. The night of D-Day saw continuous Japanese probing of the Marine positions, fire from by-passed enemy soldiers, and an enemy attack in the 4th Division zone screened by a front of civilians. The main counterattack, however, fell on the 6th Marines on the far left of the Marine lines. About 2,000 Japanese started moving south from Garapan, and by 2200 they were ready to attack. Led by tanks the charge was met by a wall of fire from .30-caliber machine guns, 37mm antitank guns, and M-1 rifles. It was too much and they fell back in disarray. In addition to 700 enemy dead, they left one tank. The body of the bugler who blew the charge was slumped over the open hatch. A bullet had gone straight up his bugle! One of the crucial assets for the Marine defense that night (and on many subsequent nights) was the illumination provided by star shells fired from Navy ships. Japanese records recovered later from their Thirty-first Army message file revealed, "... as soon as the night attack units go forward, the enemy points out targets by using the large star shells which practically turn night into day. Thus the maneuvering of units is extremely difficult."

|