| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

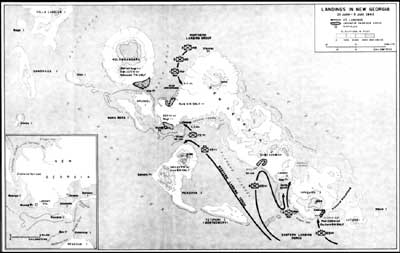

UP THE SLOT: Marines in the Central Solomons by Major Charles D. Melson, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) The New Georgia campaign began for the 1st Marine Raider Regiment when Admiral Turner received a request for support and/or rescue from the resident coastwatcher at Segi Point, Donald G. Kennedy. The Japanese were moving into his base area where the Allies planned to build an auxiliary fighter strip. Responding to the request for help, Turner loaded Lieutenant Colonel Michael S. Currin's 4th Raider Battalion on high speed destroyer transports (APDs) and sent it north to Segi Point. Captain Malcolm N. McCarthy met the raiders in a dugout canoe to guide the ships in. McCarthy felt certain that Company P's commander, Captain Anthony Walker, would have his men's weapons at the ready, and "I kept hollering, 'Hold Your Fire!'"

Currin went ashore with part of his headquarters and Companies O and P, followed by Army and Navy forces to begin the airstrip. After linking up with Kennedy, Currin turned his attention to his initial goal, the seizure of the protected anchorage at Viru Harbor. He had to accomplish this prior to the arrival of the invasion force on 30 June, and on the night of 27 June, he and his Marines set out by rubber boats across the mouths of the Akuru and Choi rivers for Viru. After an eight-mile paddle, the raiders arrived at Regi Village early on 28 June. Led by native guides, Currin began the approach march to Viru Harbor. Fighting a stubborn combination of terrain, weather, and Japanese patrols, the raiders were short of their objective on 30 June. Meanwhile, the landing force arrived on schedule and stood off the beach after taking fire from Japanese coastal defense guns.

The raiders launched their attack at 0900, l July, to seize Tetemara and Tombe Villages. Captain Walker attacked Tombe with part of his company, while the remainder attacked Tetemara with First Lieutenant Raymond L. Luckel's Company O. After six hours of fighting and a Japanese counterattack, the objectives were captured. Sergeant Anthony P. Coulis' Company P machine gun squad finished mopping up and searched for food and water. The 4th Raider Battalion lost 13 killed and 15 wounded in this action. The Japanese defenders with drew, with an estimated 61 dead and 100 wounded. Currin turned the beachhead over to the Army occupation force and was taken back on board ship and returned to Guadalcanal. The remainder of the 4th Battalion headquarters and two companies, led by battalion executive officer Major James Clark, carried out separate tasks in accordance with plans to secure Wickham Anchorage at Vangunu Island to protect lines of communication from the Russells and Guadalcanal for the New Georgia operation. On 30 June, Captain Earle O. Snell, Jr.'s Company N and Captain William L. Flake's Company Q supported an Army landing force by going ashore at Oloana Bay, where it joined a scouting party and Coastwatchers already there. Raider Irvin L. Cross later wrote that he and the other raiders disembarked from his assault transport "in Higgins Boats during a typhoon. In the dark it was impossible to see the landing craft from the deck." Despite a confused landing in poor conditions, by afternoon the Marines and units of the Army 2d Battalion, 103d Infantry reached the Kaeruka River and attacked the Japanese located there. This position was taken and then defended. A member of Company Q, John McCormick, recalled that the attack "was not very productive," but that a battle went on all day with the Japanese, who had gotten "quickly organized" and fought back with their machine guns and mortars. On 2 July, the Japanese tried to land three barges with supplies, but were met on the beach and shot up. The raiders lost 14 killed and 26 wounded securing Vangunu. The next raider deployment was like those at Viru and Vangunu, a supporting exercise to back the main XIV Corps effort to take Munda Point. Soon after the Rendova landings, Colonel Liversedge's mission was changed from being the landing force reserve to being an assault force designated the Northern Landing Group directed to attack Japanese positions on New Georgia's northwest coast at the Dragon's Peninsula.

Three of the 1st Raider Regiment's four battalions had been sent elsewhere. Liversedge's landing group consisted of the Marine raider regimental headquarters, the 1st Raider Battalion; the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry; and the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry Because the operating area was too far from the main landing force for support, fire support and supply came from the sea and air. Communications were dependent upon radio until a land-line linkup could be made with the rest of the occupation force to the south. Liversedge was assigned several tasks. First he was to land and move against the Japanese forces at Enogai Inlet and Bairoko Harbor. Then he was to block the so-called Bairoko Trail and disrupt Japanese troop and supply movements between Bairoko Harbor and Munda. The enemy, weather, and terrain together conspired against this venture from the beginning and the raiders found themselves in a protracted frontline fight rather than a swift strike in the Japanese rear. One of Liversedge's battalion commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith II, observed on embarking at Guadalcanal that although they shot off no fireworks on Independence Day, "we consoled ourselves with the knowledge that there would be plenty of those later."

On 5 July, the Northern Landing Group landed at Rice Anchorage east of Enogai and Bairoko. A narrow beach, difficult landing conditions, and concerns for an enemy naval attack caused the destroyer-transport force to depart, taking the raiders' long-range radio with it. The landing from eight APDs and destroyers (DDs) was unopposed and met only by porters and scouts (Corry's Boys) under Australian Flight Officer John A. Corrigan. Griffith described them as small men, "but their brown bodies were wiry and their arm, leg and back muscles were powerful. They wore gaudy cheap cotton lap-lap, or lavalavas." These 150 New Georgians were the Northern Landing Group's supply transport in a region without roads. Undeterred by the situation, Liversedge moved out on jungle trails in pouring rain to his first objectives, leaving two Army companies to secure the rear. In Griffith's words, they "alternately stumbled up one side of a hill and slipped and slid down the other." The 1st Raider Battalion pushed on to reach the Giza Giza River by the night of 5 July with the larger and heavier Army battalions following. Here Liversedge split his force. The 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry was sent south to block the Bairoko Trail and the remaining units went north towards the Japanese on the Dragons Peninsula. On the night of 6 July, the naval Battle of Kula Gulf erupted with the resultant loss of the cruiser USS Helena (CL 50). This isolated the Northern Landing Group from even naval support. The villages of Maranusa I and Triri were occupied and patrols were soon in contact with the enemy, members of the 6th Special Naval Landing Force, so-called Japanese "marines." On 9 July, the Enogai defenses were reached and, after an air strike, Liversedge launched an immediate attack with Lieutenant Colonel Griffith's 1st Raider Battalion. Captain Thomas A. Mullahey's Company A was on the left, Captain John P. Salmon's Company C in the center, Captain Edwin B. Wheeler's Company B on the right, with Company D under Captain Clay A. Boyd in reserve. Employing machine guns and grenades, the battalion advanced toward the Japanese position until halted at nightfall. The Japanese were well dug-in and well armed with machine guns and mortars, but their heavy-caliber coast defense artillery could only be used seaward. Supported by 60mm mortars, the raiders resumed the attack the morning of 10 July, and took Enogai Village. Richard C. Ackerman, a Marine with Company C, remembered "we soon came to a lagoon which stopped our forward motion. Our right flank, though, did over run the enemy's warehouse and food storage area." The Japanese lost 300 men at a cost of 47 Marines killed, another 74 wounded, and 4 men missing. The battalion had fought for 30 hours without rations or water resupply. Army troops carried up water and K-rations and candy bars received in an air drop. The elimination of the Japanese coast defense artillery at Enogai allowed American destroyers and torpedo boats to operate unhampered in the Kula Gulf, where they disrupted Japanese barge traffic. Under Japanese air attacks, the 1st Marine Raider Regiment consolidated its gains and blocking positions, while Colonel Liversedge studied the Bairoko Harbor defenses. Communications, resupply, and fire support were problem areas. The Japanese improved their own dispositions and continued to bring in troops and supplies from Kolombangara by sea and then moved them overland to Munda Point. The main Japanese line was on a ridge in front of the Americans. The enemy fighting positions were log and coral bunkers that made excellent use of terrain and interlocking machine-gun fire supported by heavy mortars. On the night of 12-13 July, the Navy intercepted a Japanese troop landing at Kolombangara. Four days later, on 17 July, Liversedge pulled the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry back to Triri Village for closer mutual support, while other Army companies continued to hold the Rice Anchorage area and communications routes.

Reinforced on 18 July by the 4th Raider Battalion, Liversedge planned to attack Bairoko on 20 July 1943. The attack was launched on schedule despite the failure of a requested airstrike to arrive. Liversedge sent in Griffith's battalion, followed by Currin's battalion, to find an undefended flank or a breakthrough point. Griffith committed Wheeler's Company B and Company C under First Lieutenant Frank A. Kemp. His other companies had been used to bring these two up to strength. Currin's battalion fielded four companies, but was some 200 men understrength. Companies B and C soon stalled on the Japanese defenses. Captain Walker took Company P forward for support, while Snell's Company N tried to find an open flank along the shoreline to the north. One of Snell's men, Frank Korowitz, remembered feeling that he wanted to get up and run when Japanese attacked by surprise at close range, but "I also felt that l would rather be killed than have anyone know I was scared." Liversedge fed in his remaining units to cover the gaps that developed between the two battalions and no longer had a reserve. Walker recalled, "without some kind of fire support (naval gunfire or air) these raiders could not penetrate the fortified enemy line." McCormick, with Company Q, wrote that the Japanese had plenty of time to prepare and had "machine gun pits in the natural shelter provided by the roots of banyan trees and cut fire lanes through the underbrush," The combination of machine guns, mortars, and snipers guaranteed "almost instant death" to any Marine caught in these fields of fire. At 1445, a Japanese mortar barrage was followed with a counter attack in the 1st Battalion area. After this, another assault attempted by the Marines of Company Q lead by Captain Lincoln N. Holdzkom bogged down within sight of Bairoko Harbor. By now there was a loss of almost 250 Marines, a 30 percent casualty rate. The 1st Marine Raider Regiment had 46 killed and another 200 or so wounded, and about half the wounded were litter cases. Liversedge made no further headway and withdrew that night to Enogai. It required another 150 men to move the casualties back and all units were in defensive positions by 1400, 21 July. By then, the effects of the fighting and living conditions had taken a toll in sickness and exhaustion of the Northern Landing Group. Liversedge was ordered to hold what he had with available forces. Resupply and casualty evacuation were by air and there was no further reinforcement, except a 50-man detachment under Captain Joseph W. Mehring, Jr., of the 11th Defense Battalion that provided needed 40mm and .50-caliber antiaircraft guns at Rice Anchorage.

Bairoko Harbor was attacked by destroyers and torpedo boats, and bombed by B-17 Flying Fortresses. On 2 August, XIV Corps informed Liversedge that Munda Point was reached and his force should cut off retreating Japanese near Zieta. On 9 August, the Northern Landing Group linked up with elements of the 25th Infantry Division advancing from Munda Point and assumed control of the 1st Marine Raider Regiment. Scattered fighting continued around Bairoko until 24 August when it was occupied by the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry. The Japanese defenders, the Special Naval Landing Force men, had pulled out by sea. Occupying Corrigan's "Christian Rest and Recreation" camp of thatched lean-to's, the Marines to taled their casualties for this effort; regimental headquarters had l killed and 8 wounded, 1st Raider Battalion lost 74 killed and 139 wounded, 4th Raider Battalion had 54 dead and 168 wounded; and all suffered from the unhealthy conditions of the area. By 31 August 1943, the 1st Marine Raider Regiment was back on Guadalcanal for reorganization scheduled in September, officially noting the presence of "bunks, movies, beer, chow."

|