| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

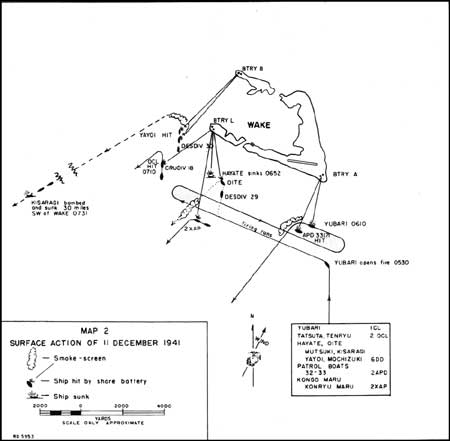

A MAGNIFICENT FIGHT: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island by Robert J. Cressman 'Humbled by Sizeable Casualties' During the night of 10 December 1941, Wake's lookouts vigilantly scanned the horizon. Those of her defenders who were not on watch grabbed what sleep they could. Shortly before midnight, the Triton was south of the atoll, charging her batteries and patrolling on the surface. At 2315, her bridge lookouts spied "two flashes" and then the silhouette of what seemed to be a destroyer, dimly visible against the backdrop of heavy clouds that lay behind her. The Triton submerged quickly and tracked the unidentifiable ship; ultimately, she fired a salvo of four torpedoes from her stern tubes at 0017 on 11 December 1941—the first torpedoes fired from a Pacific Fleet submarine in World War II. Although the submariners heard a dull explosion, indicating what they thought was at least one probably hit, and propeller noises appeared to cease shortly thereafter, the Triton's apparent kill had not been confirmed. She resumed her patrol, submerged. The ship that Triton had encountered off Wake's south coast was, most likely, the destroyer deployed as a picket 10 miles ahead of the invasion convoy steaming up from the south. Under Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka, it had set out from Kwajalein, in the Marshalls, on 8 December. It consisted of the light cruiser Yubari (flagship), six destroyers—Mutsuki, Kisaragi, Yayoi, Mochizuki, Oite, and Hayate—along with Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33 (two ex-destroyers, each reconfigured in 1941 to launch a landing craft over a stern ramp) and two armed merchantmen, Kongo Maru and Kinryu Maru. To provide additional gunfire support, the Commander, Fourth Fleet, had also assigned the light cruisers Tatsuta and Tenryu to Kajioka's force.

Admiral Kajioka faced less than favorable weather for the endeavor. Deeming the northeast coastline unsuitable for that purpose, invasion planners had called for the converted destroyers to put 150 men ashore on Wilkes and 300 on Wake. If those numbers proved insufficient, Kajioka's supporting destroyers were to provide men to augment the landing force. If contrary winds threatened the assault, the troops would land on the northeastern and north coasts. Since the weather had moderated enough by the 11th, though, the force was standing toward the atoll's south, or lee, shore in the pre-dawn hours. confident that two days of bombings had rendered the islands' defenses impotent. Meanwhile, far to the east, at Pearl Harbor, the Pacific Fleet continued to pick up the pieces after the shattering blow that the Japanese had delivered on the 7th. The enemy onslaught had forced Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (CinCPac), to revise his strategy completely. Kimmel wanted to relieve Wake, but deploying what remained of his fleet to protect sea communications, defend outlying bases, and protect far-flung territory, as well as to defend Oahu, would have required a wide dispersal of the very limited naval forces. By 10 December (11 December on Wake), the scattered positions of his aircraft carriers, which were at sea patrolling the Oahu-Johnston-Palmyra triangle, militated against deploying them to support Wake. Cunningham's garrison, however, in a most striking fashion, would soon provide inspiration to the Pacific Fleet and the nation as well. Wake's lookouts, like Triton's,, had seen flickering lights in the distance. Gunner Hamas, on duty in the battalion command post, received the report of ships offshore from Captain Wesley McC. Platt, commander of the strongpoint on Wilkes, and notified Major Devereux, who, along with his executive officer, Major George H. Potter, stepped out into the moonlight and scanned the southern horizon. Hamas also telephoned Cunningham, who ordered the guns to hold fire until the ships closed on the island.

Cunningham then turned to Commander Keen and Lieutenant Commander Elmer B. Greey, resident officer-in-charge of the construction programs at Wake, with whom he shared a cottage, and told them that lookouts had spotted ships, undoubtedly hostile one, standing toward the atoll. He then directed the two officers to alert and immediately headed for the island's communications center in his pickup truck. As the Japanese ships neared Wake, the Army radio unit on the atoll sent a message from Cunningham to Pearl Harbor at 0200 on the 11th, telling of the contractors' casualties, and, because of the danger that lay at Wake's doorstep, suggested early evacuation of the civilians. Army communicators on Oahu who received the message noted that the Japanese had tried to jam the transmission. At 0400, Major Putnam put VMF-211 on the alert, and soon thereafter he and Captains Elrod, Tharin, and Freuler manned the four operational F4Fs. The Wildcats, a 100-pound bomb under each wing, then taxied into position for take-off. Shortly before 0500, Kajioka's ships began their final run. At 0515, three wildcats took off, followed after five minutes by the fourth. They rendezvoused at 12,000 feet above Toki Point. At 0522, the Japanese began shelling Wake. The Marines' guns, however, remained silent as Kajioka's ships "crept in, firing as they came." The first enemy projectiles set the oil tanks on the southwest portion of Wake ablaze while the two converted destroyers prepared to land their Special Naval Landing Force troops. The column of warships advanced westward, still unchallenged. Nearing the western tip of Wake 20 minutes later, Kajioka's flagship, the Yubari, closed to within 4,500 yards, seemingly "scouring the beach" with her 5.5-inch fire. At 0600, the light cruiser reversed course yet again, and closed the range still further. The Yubari's maneuvering prompted the careful removal of the brush camouflage, and the Marines began to track the Japanese ships. As the distance decreased, and the reports came into Devereux's command post with that information, the major again told Gunner Hamas to relay the word to Commander Cunningham, who, by that point, had reached his command post. Cunningham upon receiving Hamas' report, responded, "What are we waiting for, open fire. Must be Jap ships all right." Devereux quickly relayed the order to his anxious artillerymen. At 0610, they commenced firing.

Barninger's 5-inchers at Peacock Point, Wake's "high ground" behind them, boomed and sent the first 50-pound projectiles beyond their target. Adjusting the range quickly, the gunners soon scored what seemed to be hits on the Yubari. Although Barninger's guns had unavoidably revealed their location, the ships' counterfire proved woefully inaccurate. Kajioka's flagship managed to land only one shell in Battery B's vicinity, a projectile that burst some 150 feet from Barninger's command post. "The fire ... continued to be over and then short throughout her firing," Barninger later reported. "She straddled continually, but none of the salvoes came into the position. "It was fortunate that the Japanese fire proved as poor as it was, for Barninger's guns lay completely unprotected, open save for camouflage. No sandbag protection existed! Captain Platt, meanwhile, told Major Potter via phone that, since Battery L's rangefinder had been damaged in the bombing the previous day, First Lieutenant McAlister was having trouble obtaining the range. After Platt passed along Potter's order to McAlister to estimate it, Battery L opened fire and scored hits on one of the transports, prompting the escorting destroyers to stand toward the troublesome guns. Platt carefully scrutinized the Japanese ship movements offshore, and noted with satisfaction that McAlister's 5-inchers sent three salvoes slamming into the Hayate. She exploded immediately, killing all of here 167-man crew. McAlister's gunners cheered and then turned their attention to the Oite and the Mochizuki, which soon suffered hits from the same guns. The Oite sustained 14 wounded; the Mochizuki sustained an undetermined number of casualties. First Lieutenant Kessler's Battery B, at the tip of Peale, meanwhile, dueled with the destroyers Yayoi, Mutsuki and Kisaragi, as well as the Tenryu and the Tatsuta, and drew heavy counterfire that disabled on gun. The crew of the inoperable mount shifted to that of a serviceable one, serving as ammunition passers, and after 10 rounds, Kessler's remaining gun scored a hit on the Yayoi's stern, killing one man, wounding 17, and starting a fire. His gunners then sifted their attention to the next destroyer in column. The enemy's counterfire severed communications between Kessler's command post and the gun, but Battery B—the muzzle blast temporarily disabling the range finder—continued with local fire control. As the Japanese warships stood to the south, Kessler's gun hurled two parting shots toward a transport, which proved to have been out of range.

The Yubari's action record reflects that although Wake had been pounded by land-based planes, the atoll's defenders still possessed enough coastal guns to mount a ferocious defense, which forced Kajioka to retire. As if the seacoast guns and the weather were not enough to frustrate the admiral's venture—the heavy seas had overturned landing boats almost as soon as they were launched—the Japanese soon encountered a new foe. While Cunningham's cannoneers had been trading shells with Kajioka's, Putnam's four Wildcats had climbed to 20,000 feet and maintained that altitude until daylight, when the major had ascertained that no Japanese planes were airborne. As the destroyers that had dueled Battery B opened the range and stood away from Wake, the Wildcats roared in. Major Putnam saw at least one of Elrod's bombs hit the Kisaragi. Trailing oil and smoke, the damaged destroyer slowed to a stop but then managed to get underway again, internally afire. While she limped away to the south, Elrod, antiaircraft fire having perforated his plane's oil line, headed home. He managed to reach Wake and land on the rocky beach, but VMF-211's ground crew wrote off his F4F as a total loss. Meanwhile, Tenryu came under attack by Putnam, Tharin, and Freuler, who strafed her forward, near the number 1 torpedo tube mount, wounding five men and disabling three torpedoes.

The three serviceable Wildcats then shuttled back and forth to be rearmed and refueled. Putnam and Kinney later saw the Kisaragi—which had been carrying an extra supply of depth charges because of the American submarine threat—blow up and sink, killing her entire crew of 167 men. Freuler, Putnam, and Hamilton strafed the Kongo Maru, igniting barrels of gasoline stowed in one of her holds, killing three Japanese sailors, and wounding 19. Two more men were listed as missing. Freuler's Wildcat took a bullet in the engine but managed to return to the field. Technical Sergeant Hamilton reached the field despite a perforated tail section. The Triton, which had not made contact with an enemy ship since firing at the unidentified ship during the pre-dawn hours, did not participate in the action that morning. Neither did her sistership, the Tambor. The latter attempted to approach the enemy ships she observed firing at the atoll, until they appeared to be standing away from Wake. Then, she reversed course and proceeded north, well away from the retiring Japanese, to avoid penetrating the Triton's patrol area. Meanwhile, after Kinney witnessed the Kisaragi's cataclysmic demise, he strafed another destroyer before returning to the field. Having been rearmed and refueled, he took off again at 0915, accompanied by Second Lieutenant Davidson, shortly before 17 Nells appeared to bomb Peale's batteries.

Davidson battled nine of the bombers, which had separated from the others and headed toward the southwest. Kinney tackled the other eight. Battery D, meanwhile, hurled 125 rounds at the bombers. Although some of the enemy's bombs fell near the battery position on Peale, the Japanese again inflicted neither damage nor casualties, and lost two Nells in the process. Eleven other G3M2s had been damaged; casualties included 15 dead and one slightly wounded. Putnam later credited Kinney and Davidson with shooting down one plane apiece. Ordered to move Battery D's 3-inch guns the length of Peale during the night, Godbold reconnoitered the new position selected by Major Devereux, and at 1745, after securing all battery positions, began the shift. For the next 11 hours, the Marines, assisted by nearly 250 civilians, constructed new emplacements. By 0445 on 12 December, Godbold could again report: "Manned and ready." At Peacock Point, on the night of the 11th, Wally Lewis gave permission for all but two men at each gun, and at the director, to get some sleep—the first the men had had in three days. The Japanese force, meanwhile, "... humbled by sizeable casualties," withdrew to the Marshalls, having requested aircraft carrier reinforcement. Hundred of miles away, at Pearl Harbor, elements of the 4th Defense Battalion received orders to begin preparing for an operation, the destination of which was closely held. The Marines of the battalion fervently desired to assist their comrades on Wake Island and many of them probably concluded, "We're headed for Wake!"

|