| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

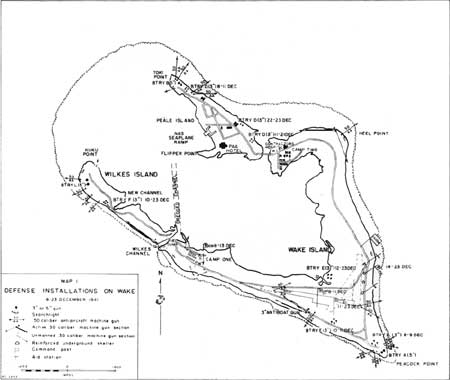

A MAGNIFICENT FIGHT: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island by Robert J. Cressman It is Monday, 8 December 1941. On wake Island, a tiny sprung paper-clip in the Pacific between Hawaii and Guam, Marines of the 1st Defense Battalion are starting another day of the backbreaking war preparations that have gone on for weeks. Out in the triangular lagoon formed by the islets of Peale, Wake, and Wilkes, the huge silver Pan American Airways Philippine Clipper flying boat roars off the water bound for Guam. The trans-Pacific flight will not be completed. Word of war comes around 0700. Captain Henry S. Wilson, Army Signal Corps, on the island to support the flight ferry of B-17 Flying Fortresses from Hawaii to the Philippines, half runs, half walks toward the tent of Major James P.S. Devereux, commander of the battalion's Wake Detachment. Captain Wilson reports that Hickam Field in Hawaii has been raided.

Devereux immediately orders a "Call to Arms." He quickly assembles his officers, tells them that war has come, that the Japanese have attacked Oahu, and that Wake "could expect the same thing in a very short time."

Meanwhile, the senior officer on the atoll, Commander Winfred S. Cunningham, Officer in Charge, Naval Activities, Wake, learned of the Japanese surprise attack as he was leaving the mess hall at the contractors' cantonment (Camp 2) on the northern leg of Wake. He ordered the defense battalion to battle stations, but allowed the civilians to go on with their work, figuring that their duties at sites around the atoll provided good dispersion. He then contacted John B. Cooke, PanAm's airport manager and requested that he recall the Philippine Clipper. Cooke sent the prearranged code telling John H. Hamilton, the captain of the Martin 130 flying boat, of the outbreak of war.

Marines from Camp 1, on the southern leg of Wake, were soon embarked in trucks and moving to their stations on Wake, Wilkes, and Peale islets. Marine Gunner Harold C. Borth and Sergeant James W. Hall climbed to the top of the camp's water tower and manned the observation post there. In those early days radar was new and not even set up on Wake, so early warning was dependent on keen eyesight. Hearing might have contributed elsewhere, but on the atoll the thunder of nearby surf masked the sound of aircraft engines until they were nearly overhead. Marine Gunner John Hamas, the Wake Detachment's munitions officer, unpacked Browning automatic rifles, Springfield '03 rifles, and ammunition for issue to the civilians who had volunteered for combat duty. That task completed, Hamas and a working party picked up 75 cases of hand grenades for delivery around the islets. Soon thereafter, other civilians attached themselves to marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211, which had been on Wake since 4 December.

Offshore, neither Triton (SS-201) nor Tambor (SS-198), submarines that had been patrolling offshore since 25 November, knew of developments on Wake or Oahu. They both had been submerged when word was passed and thus out of radio communication with Pearl Harbor. The transport William Ward Burrows (AP-6), which had left Oahu bound for Wake on 27 November, learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl while she was still 425 miles from her destination. She was rerouted to Johnston Island. Major Paul A. Putnam, VMF-211's commanding officer, and Second Lieutenant Henry G. Webb had conducted the dawn aerial patrol and landed by the time the squadron's radiomen, over at Wake's airfield, had picked up word of an attack on Pearl Harbor. Putnam immediately sent a runner to tell his executive officer, Captain Henry T. Elrod, to disperse planes and men and keep all aircraft ready for flight.

Meanwhile, work began on dugout plane shelters. Putnam placed VMF-211 on a war footing immediately; two two-plane sections then took off on patrol. Captain Elrod and Second Lieutenant Carl R. Davidson flew north, Second Lieutenant John F. Kinney and Technical Sergeant William J. Hamilton flew to the south-southwest at 13,000 feet. Both sections were to remain in the immediate vicinity of the island.

The Philippine Clipper, meanwhile, had wheeled about upon receipt of word of war and returned to the lagoon it had departed 20 minutes earlier. Cunningham immediately requested Captain Hamilton to carry out a scouting flight. The Clipper was unloaded and refueled with sufficient gasoline in addition to the standard reserve for both the patrol flight and a flight to Midway. Cunningham, an experienced aviator, laid out a plan, giving the flying boat a two-plane escort. Hamilton then telephoned Putnam and concluded the arrangements for the search. Take-off time was 1300.

Shortly after receiving word of hostilities, Battery B's First Lieutenant Woodrow M. Kessler and his men had loaded a truck with equipment and small arms ammunition and moved out to their 5-inch guns. At 0710, Kessler began distributing gear, and soon thereafter established a sentry post on Toki Point at the northermost tip of Peale. Thirty 5-inch rounds went into the ready-use boxes near the guns. At 0800, re reported his battery ready for action. General quarters called Captain Bryghte D. "Dan" Godbold's men of Battery D to their stations down the coast from Battery B at 0700, and they moved out to their position by truck, reporting "manned and ready" within a half hour. The lack of men, however, prevented Godbold from having more than three of his 3-inch guns in operation. Within another hour and a half, each gun had 50 rounds ready for firing. At 1000, Goldbold received orders to keep one gun, the director, the heightfinder (the only one at Wake Island for the three batteries), and the power plant manned at all times. After making those arrangements, Godbold put the remainder of his men to work improving the battery position.

|