| The War in the Pacific |

|

LIBERATION — Guam Remembers A Golden Salute for the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of Guam Chamorros yearn for freedom I can't think of anything that has happened to me lately that has touched me as much as being asked to recall and record in writing, as part of our commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Guam, some of the significant events that have transpired over the recent years that stand out in my memory. To this day, whenever we speak of the period before the "war" and after the "war" we invariably mean World War II. We do this almost subconsciously despite that sons and daughters of Guam have been involved in other wars since World War II: in Korea, Vietnam and the Persian Gulf. The invasion, occupation and eventual liberation of Guam made such an indelible impact on our people that it is likely to serve as the benchmark, the road junction, and the springboard for what we do for many, many years to come.

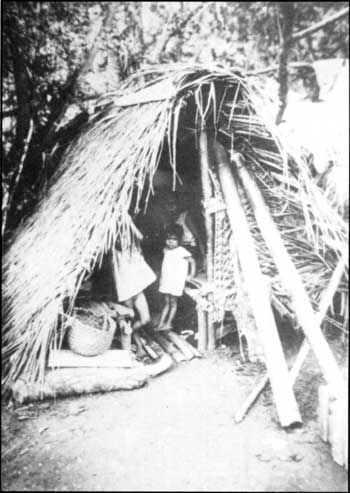

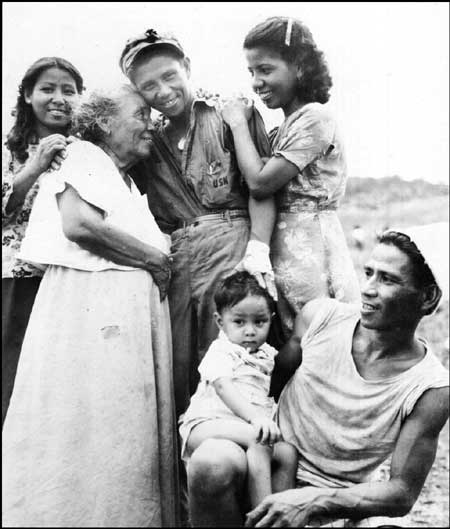

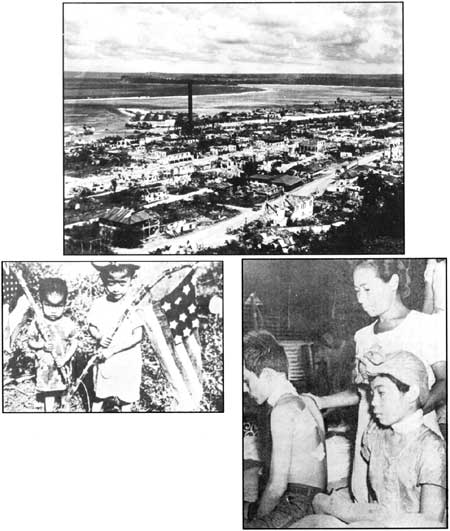

While this difficult period deprived those of my generation most of our tender teen years, it taught us more about life, family and ourselves than I, for one, had ever learned before or since in all the schools I have attended. The Chamorro spirit was not an abstraction; rather, it was demonstrably real during those years and I have drawn inspiration and sustenance from that reality my entire life. Our World War II experience was harsh by any standard. Severe deprivation, indignities, and punishment were common place. There was always that pervasive sense of personal insecurity. Most members of my generation as well as the older generation prefer not to dwell on the scars of those difficult years. But those of us who survived the trial of the war years bear witness to a side of the occupation that I will call the "inner Guam," one that the enemy was never privileged to enter. It was the purest product of that cauldron of war, the brightest star in the dark sky of those traumatic times. They would recall, as I do, the manifestation and magnificence of the Chamorro spirit. Though only a legend to some, it is a living, breathing reality to us; a source of strength that saw us through the worst of times and guides us in the challenging times ahead. My generation was caught between childhood and adulthood. The unexpected and violent interruption of our lives and the common adversity that we shared gave our parents and elders an unusual opportunity to inculcate in us much more vital learning than we could have received in calmer times. Challenged by the threatening experience of war and pressed to our limits, we learned things about human nature and ourselves that we might never have been able to grasp in peaceful, less demanding, times. We learned: to be tolerant when conditions were intolerable; to be generous when there was so little to give; to be patient when our deepest desire was to end our bondage; to be ourselves, preserving our language and culture while the enemy was trying to impose his on us. Life seemed more endangered, more tentative, and therefore, more precious then. We learned through toil the sweetness of the saltiness of the sweat that trickled down our faces at the peak of a hard day's work. We clearly saw and keenly appreciated the basic choices of life, between freedom and bondage; justice and oppression; hope and despair; surviving and perishing. Through the heat and dust and smoke, we saw ourselves and what we stood for. There were many painful experiences in that dark period in our history. But there were also many pleasant memories: —The long hours on a log with our parents sharing their thoughts and experiences with us much like the generations before them had done; but with greater urgency as the winds of war swirled around the island; —The groups of neighboring farmers who pooled their strength to push back the jungle so we could plant; The women caring for the sick, working the gardens preparing food over open fires; —The men echoing each other's folksong at twilight as they cut tuba; —The labor camps where we realized how we had to protect each other, how we had to care for one another as an island family; —The devout men and women who emerged as our natural leaders and who would always lead us in prayer during our most trying and fearful moments as we labored to finish our forced labor projects under incredible duress; —There was the young Japanese officer who taught me elementary Japanese in exchange for my father teaching him English and who, after getting to know us, innocently asked by father why we were at war; —There was this same officer who came to say good-bye and as he left to defend against the invasion, I felt an indescribably mixed emotion of seeing a new friend leaving to fight those coming to liberate us; —There were the U.S. Marines, the soldiers, the sailors and the Coast Guardsmen who, after hopping from island to island, liberated one of their own and seemed as glad as we were that they had come back to Guam; —And there were the joyous faces of my fellow Chamorros, 23,000 strong, who had endured 31 months of harsh enemy occupation, including internment in concentration camps, in a war they had no part in starting. As excruciating and as harrowing as the occupation was, our people did not surrender without a fight and did not stop fighting after the surrender. In the face of an overwhelmingly larger enemy force, a handful of U.S. sailors and Marines stood their ground. Standing beside them, with equal valor and courage but even with greater pride and determination, were the members of the Navy Insular Force Guard. For these men, Chamorros all, the defense of Guam meant the defense of home, family and honor. Although they wore the same U.S. Navy uniforms, their pay was exactly one-half that of the stateside comrades. Although they fought under the same U.S. flag, they were considered only half-brothers in the patronizing, colonial society on Guam at that time. Yet, when it came time to shed blood against foreign invaders, the Chamorros of the Navy Insular Force demonstrated their loyalty to the United States in the same way they demonstrated their love for the U.S. principles of freedom and democracy: not halfheartedly, but totally and wholeheartedly. It is that commitment to home, family and honor that has sustained us over the years as a people. In the years since Magellan landed on Guam, our people have been colonized, proselytized, Catholicized, and subsidized. Guam has fallen under Spanish, American, Japanese and again American rule. But never have we been asked what we as a people wanted. Progress, whatever there was of it, moved at a pace of the administering authority. It was his choice to uncover or cover at his will what he wished to know about us, and it was our lot to remain mute to the process. The attitude developed that the foreigners' right to dominate the land was established by their finding it, and the people - like the flora and fauna - had no alternative but to acquiesce in silence. The Spaniards made Guam their own, but never did they ask the Chamorro people, the Old People, what relationship should be forged with them. Nor, centuries later, when the United States took control of the island did it ask the descendants of those Chamorros and those Spaniards what association should be formed. We must wonder why the colonizing forces never asked this most fundamental question. Perhaps they felt that the new order they were bringing was so progressive that the people could not help but be overjoyed to embrace it. Or perhaps the ugly hand of racism was at work, and they believed the people could not tell the difference between freedom and subjugation. Whatever the case, with the close of the war and with increased education opportunities becoming available to the people of Guam, those of my generation realized the disparities we had accepted without question for so long did not have to be the case. It was as if we had been born blind and then miraculously had been given sight. It came as a shock to realize that darkness was not inevitable nor the natural state of the world. And so it was we who realized that we were not a second class people. Invisible barriers were just that — invisible and without reason. New horizons revealing incredible vistas began to open before us. We had been told for generations, for example, that should we join the Navy, we were worthy to serve as servants, as stewarts. My generation began to ask: And why not officers? There was no reply. And so slowly at first, and then with accelerating force, we set out on a quest to achieve our self-determination as a people — economically, culturally, and politically.

Genuine self-determination, if the word is to have any meaning, is a self-help program. If you truly want it, if it truly means anything to you, you must reach out for it and grasp it as your own. That we have done. During the 25th anniversary celebration in 1969, one of the most distinguished officers in the Marine Corps, Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, was our guest of honor. Having commanded one of the major units that liberated Guam, Gen. Shepherd had a very special place in his heart for the people of Guam and, in particular for those under his command who were killed in action during the fighting. I remember still his closing remarks before a full house at the Guam Legislature: "When I get to heaven," he said, "my men who died here during the war will be at the gate waiting for me with this question: 'Lem, was dying for Guam worth it?' My answer to them will be that having just visited Guam recently, the answer is, you damn right it was." In closing my recollections of this very auspicious occasion, I cannot resist the urge to share an exchange I had with my own father as I was about to leave Guam after spending a week's leave following my graduation from Notre Dame and my being commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marines. Departing with me that day was a group of young Guamanians who had just been recruited in the Army and on their way to basic training. As with me, most of them would eventually find themselves serving in Korea. Unlike me, however, some of them would die there and others would return home with lives and limbs shattered forever. It made for a large group, the recruits and their mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, and me and my family. We made our way to the tarmac for our final good-byes, and as I gathered my things for boarding, my father grabbed my arm.

In his eyes was the old fierceness, and despite his failing health, he was the robust and feisty man who had been a boxer and a fighter for equality. To my utter amazement, he said to me, "Since you are now an officer of the United States, Lieutenant, answer me this. Why is it that we are treated as equals only in war but not in peace?" Still holding my arm, he pulled me to him and said, "You don't have to answer now. Just remember that the quest must endure." My chest was tight as I said, "Yes, Sir."

As I finished kissing him good-bye, he whispered, "By the way, you never did return the salute I gave you when you first arrived." I stepped back from him, and standing ramrod straight, I brought my hand to my forehead in a crisp salute but my arm was trembling from the unexpected and affectionate admonition from my Navyman father. To this day, my father's question continues to haunt all of us, but at least we now have that question formalized and on the Congressional table - the Commonwealth of Guam. On this, the 50th anniversary of our liberation, we will be shedding a few tears — of gratitude to our liberators; of remembrance of our brothers and sisters who suffered with us but are unable to join us; and of thanksgiving as we thank Almighty God for all the blessings that have come our way during these golden years. But after those tears have stopped and have become a precious memory for us all, we must remember that the work begun by the Liberators in 1944 is not yet complete. The people of Guam picked up the torch of freedom passed to them on July 21, 1944. All who call Guam home have worked so hard and so determinedly that the entire world can see the island and its people have come so far from that terrible time of long ago. But true self-determination and equality still evade our people. Thus, the quest endures.

|