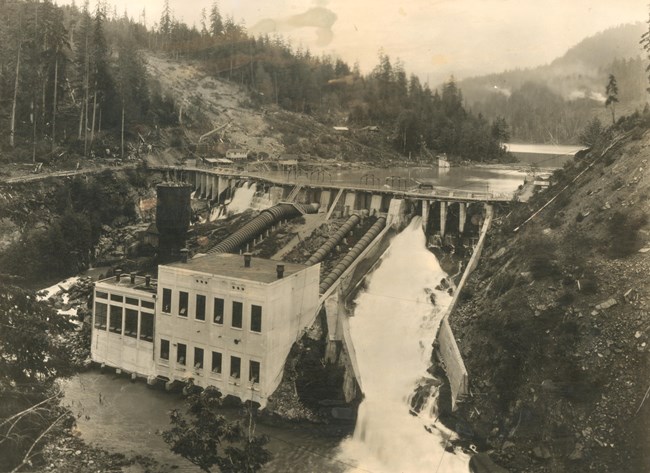

NPS Photo In the early 1900s, Canadian entrepreneur Thomas Aldwell saw the river and its narrow gorges as an economic opportunity. He sought to harness the powerful energy of the river to grow the emerging town of Port Angeles and crafted plans to build a hydroelectric dam. With financial backing from Chicago investors, the Olympic Power Company was formed, and the construction of the Elwha Dam began in 1910. Functional in 1913, the Elwha Dam supplied energy to a pulp mill in Port Angeles, ultimately supporting the growing logging industry in the region. As the economy grew, energy demands increased and plans to construct a second dam were solidified. By 1927, Glines Canyon Dam was built eight miles upstream of the Elwha Dam.

Though power generated by the dams helped to fuel the local economy in the first half of the century, contractors failed to include fish passage in dam construction. This left returning sea-run fish with a mere five miles of accessible habitat from the mouth of the river. The dams also blocked large volumes of sediment behind their walls, leading to the erosion of riverbanks and the deterioration of suitable spawning habitats downstream. Dam construction had numerous impacts on the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe historically residing along the river’s banks. Multiple areas of religious significance were flooded, and spiritually and economically valuable salmon populations were decimated.

By the 1980s, salmon populations were threatened across the entire Pacific Northwest region and questions of policy regarding dam licensing within a national park were emerging. After several years of political jockeying, Congress settled the issue in 1992 by passing the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act. Public Law 102-495 authorized the Secretary of the Interior to acquire the two hydroelectric dam projects and implement the actions necessary to achieve full restoration of the Elwha River and the native anadromous fisheries therein. Following the completion of a thorough environmental impact statement, the US Department of the Interior proposed the decommissioning and removal of both the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams to fully restore the Elwha River ecosystem. The Elwha Dam was removed in 2011, followed by the Glines Canyon Dam in 2014. |

Last updated: March 28, 2025