Courtesy T.J. Fudge, Univ. of Washington What can be 900 feet thick, move several feet a day, and carve out any solid rock in its way? The Blue Glacier, a 2.6-mile long glacier that descends from 7,980-foot Mount Olympus, the highest peak in the Olympic Mountains. Blue Glacier is one of the park's largest; one researcher calculated it would be equivalent to 20 trillion ice cubes! The glaciers of the Olympic Mountains and the neighboring Cascades helped sculpt the wild, beautiful landscape that attracts millions of visitors to Olympic, North Cascades and Mount Rainier National Parks. They comprise the most glaciated area of the United States outside of Alaska. Their meltwater combines with annual snowpack to feed rivers, forests and lowland communities en route to the sea, and nurture cold-water-loving fish like salmon and bull trout. The yawning crevasses challenge climbers who use ropes, crampons and ice axes to ascend the high peaks. They have had a powerful role in the past but also offer insights into our future.

Glaciers of the Past Over thousands of years gravel embedded in glacial ice has carved away at Olympic rock as the glaciers flow downhill, leaving behind smoothed rocks, sharp ridges and lake-filled basins. In the fastest sections, the Blue Glacier is moving about 3 feet a day. At the top, glacial ice eats away at the mountain embracing it, eventually carving a bowl-like cirque where lakes often form. Continental Glaciers

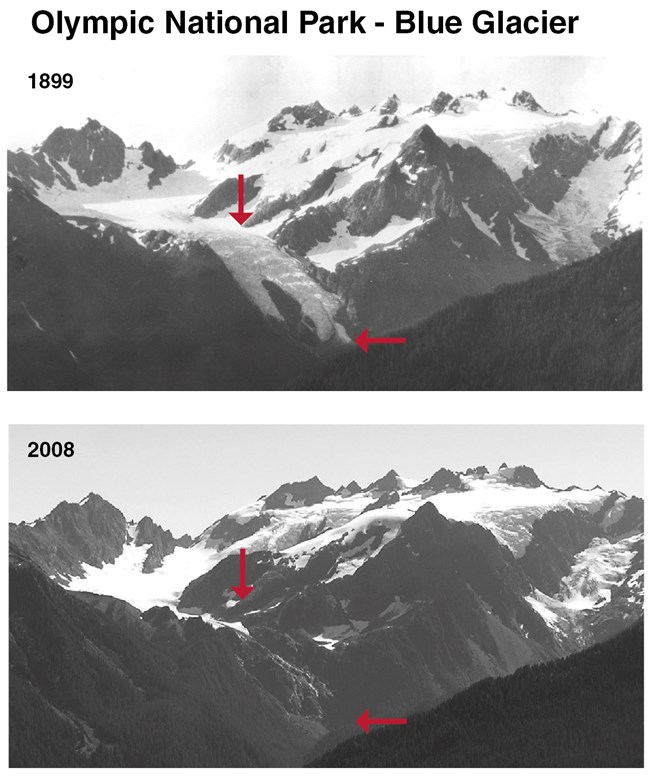

1899: Olympic National Park archives Glaciers in the Present and Future The Olympic Mountains are tall enough and far enough north (48° latitude) that much of the moisture they rake from storms falls as snow. Each year 50-70 feet (15-22 m) of snow can fall on Mount Olympus, feeding the Blue and other glaciers on its flanks. The Blue Glacier is one of the most studied glaciers in the world. For decades researchers have been observing, photographing, and measuring the glacier to read the stories written on its icy pages. The Climate Story Told in Ice Because they grow or shrink in response to snowfall and snowmelt, glaciers are sensitive indicators of changes in regional and global climate. To grow, a glacier must receive more snow in winter than melts or evaporates the following summer. If more melts than accumulates, a glacier will shrink. As Earth’s climate warms, rapid loss of glacial ice is being documented around the world. Olympic is no different; in fact temperatures at higher elevations and latitudes are warming the fastest. As a result, more of the precipitation that used to fall as snow, feeding the glaciers, is now falling as rain.

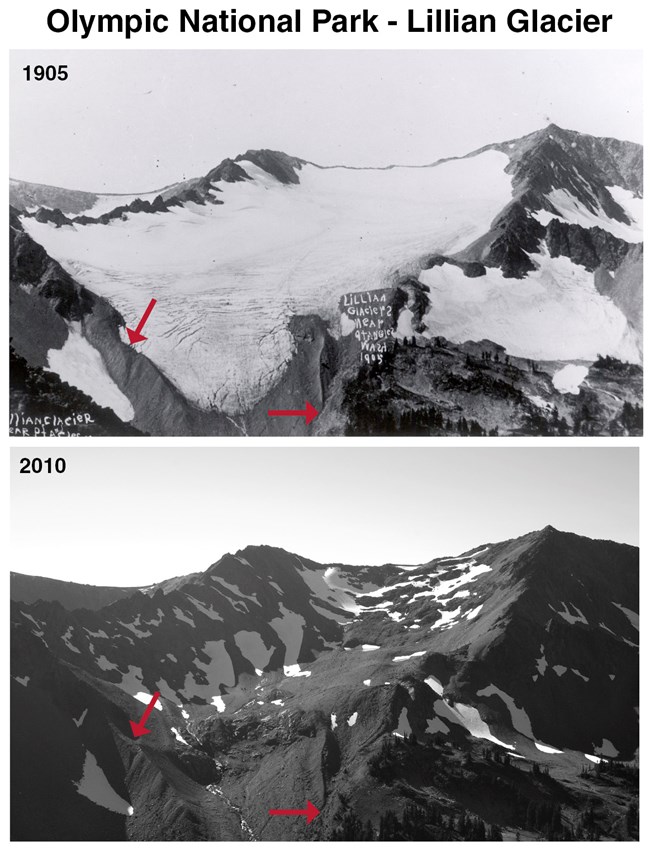

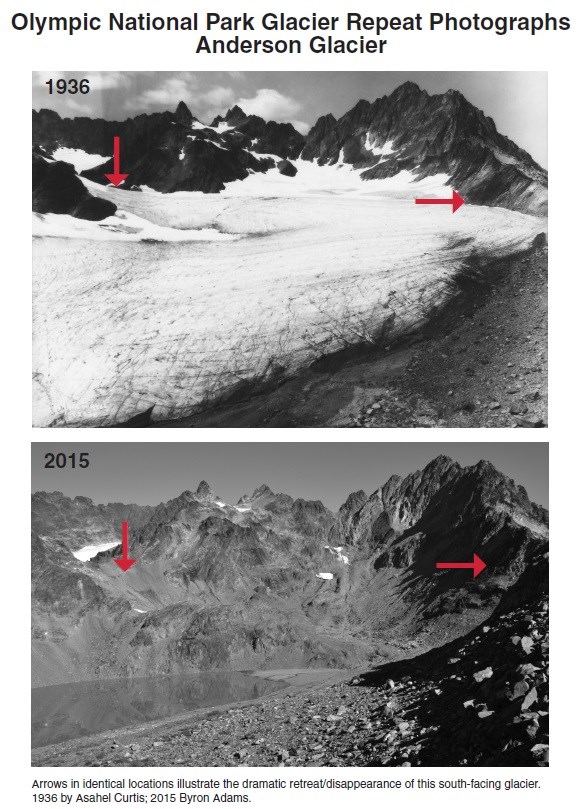

Olympic National Park Disappearing Glaciers What does that mean for Olympic’s glaciers? Since these rivers of ice are critical resources, in 2009 Olympic National Park did a new glacier inventory examining surface area as well as elevations of larger glaciers to calculate the volume of ice loss and impacts on the park’s glacial-fed rivers. In an area known for its rain, summers are actually quite dry. Glacier melt is an important part of maintaining summer flows for aquatic life that depends on these lifelines. Results were sobering. In 1982, the park had 266 glaciers; in 2009 there were 184. Comparison photographs clearly show glaciers in retreat. By comparing aerial photos from the late 1970s to 2009, researchers detected a 34% loss of glacier surface area in only 30 years. The terminus (bottom end) of the Blue Glacier retreated about 325 feet (100 m) in the 20 years from 1995-2006. On Mount Anderson, a rugged peak in the southeastern part of the park, its south-facing Anderson Glacier receded to less than 10% of its former size between 1927 and 2009, and was essentially gone by 2015!" But length is only a small part of the story; the glaciers are also getting thinner. Researchers found the volume of ice decreased by at least 15% in the 22 years from 1987-2009. For example, surface measurements revealed Blue Glacier terminus lost 178 feet (55 m) of thickness between 1987 and 2009. Even the snowier upper glacier lost 32-48 feet (10-15 m). These critical and beautiful rivers of ice have shaped and adorned the Olympic Mountains for millennia, but have rapidly shrunk in just decades, stark evidence of the ongoing impact of human-driven climate change. Their ice is an essential resource for creatures from tiny ice worms found only on glacial ice, to steelhead and salmon returning up snow and ice-fed rivers, and even to humans living downstream or climbing to the icy heights. The data and photographs are clear. What’s unclear is if humans will to make the changes necessary to help these icons of the Pacific Northwest summits persist.

1936: Asahel Curtis Links for more Information See links below for how you can help or to learn more about glacier and climate change studies. http://www.globalchange.gov - This site integrates federal research on climate and global change. http://nsidc.org/sotc - Site for the National Snow and Ice Data Center. https://www.nps.gov/ http://www.ess.washington.edu/surface/Glaciology/ projects/blue_glac/blue.html - University of Washington site for Blue Glacier research. http://glaciers.us - Glaciers of the American West site, a project at Portland State University with funding from the National Science Foundation, NASA, the US Geological Survey, and the National Park Service. |

Last updated: April 17, 2025