C&O Historical Society

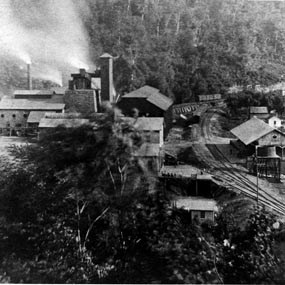

C&O Historical Society The town Quinnimont received its name from the five mountains surrounding it. Jacob Smith settled the land in 1827 making it the oldest European settled town in the New River Gorge. The fertile land along the New River at the bottom gorge made it excellent for small farming. Over the years, the town grew into a community of subsistence farming living off the land. Industry Brings ChangeBig changes came to the sleepy farming town in 1870. Industry entered the New River Gorge as people discovered the coal mining opportunities. In Quinnimont, industrialization began with the Charter Oak and Iron Company's iron furnace. In 1872, Joseph Beury arrived in Quinnimont and opened his first coal mine in New River Gorge. Only a few years later in 1873, the main line of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad opened. Quinnimont's mine shipped the first load of coal from the New River Gorge in the fall of 1873. Throughout the mining years, Quinnimont remained a major coal shipping town.

C&O Historical Society At its peak, Quinnimont had a population of over 500 residents. The town had a railroad station with two daily passenger trains. These trains offered commutes to the town of Beckley and the town of Layland near Laurel Creek. Like many towns, Quinnimont had a general store, post office, and hotel. There was also a baseball field for local mining teams, a jail, and railroad boarding houses. In the later years, the town built a roadside park along with a service station and diner. The mine also added a coal loading facility and coal tipple to help with mining operations. SegregationSegregation was an unfortunate reality in the New River Gorge communities. Mining companies used this practice to prevent unionization efforts. They segregated houses between racial and ethnic groups. Welsh and English from Irish, Italians from Polish, and Blacks from Whites. Quinnimont also practiced segregation and had two churches and two schools. White residents used one church and school and black residents used the others. Despite these attempts at segregation in the towns, the mines were not segregated. Miners depended on each other for safety no matter the skin color or background. Breakthroughs against segregation and for unionization were happening in the mines. As one miner said, “We are all black at the end of the day when we come out of that hell hole.”

NPS Quinnimont TodayDuring the peak of the coal mining industry, there was a coal town every half mile along the gorge. But by the 1950s, most of the mines closed and the people living in the mine towns left. These abandoned towns fell into decay and disappeared into the forest. But Quinninmont lives on as an active community because of its connection to the road and rails. Today, visitors to Quinnimont will see active CSX railroad switching and holding yards. Remnants of the old town are visible by driving WV-41 through the park. The two segregated churches, now abandoned, still stand on a side road from the main road. The black church is part of the African American Heritage Driving Tour. Also remaining are the ruins of the iron furnace that brought industry to Quinnimont. A tall granite monument stands in a field to commemorate Colonel Joseph Beury. More New River Gorge History

|

Last updated: August 24, 2023