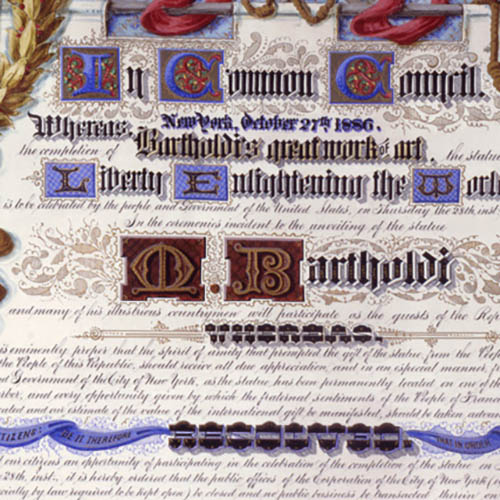

Opening Ceremony

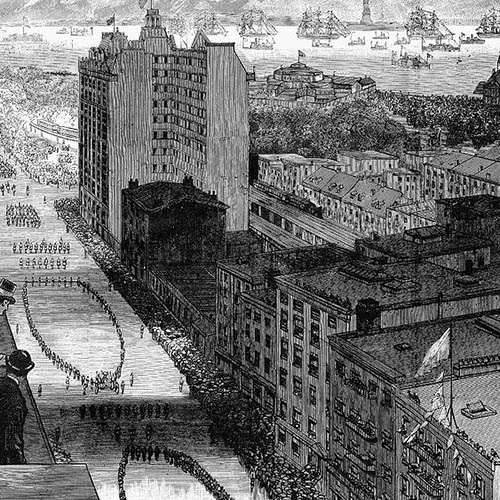

On a rainy October 28, 1886, the Statue of Liberty was officially unveiled in the United States. Organized by the Franco-American Union and the City of New York, the dedication ceremonies celebrated the Statue’s creators and contributors, the people of France and the United States. Over a million people attended the festivities both on the island and throughout the city, including Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi and French and American dignitaries. Édouard René Lefèbvre de Laboulaye, considered the father of the Statue of Liberty, died in 1883 and did not see its dedication.

Firefighters, soldiers, and veterans—including the 20th Regiment of US Colored Troops—marched down Broadway to the sounds of 100 brass bands, cannons, and sirens. On Bedloe’s Island, prominent men, including US President Grover Cleveland, praised the Statue’s promise of liberty.

Unveiling Liberty

“The dream of my life is accomplished; I see the symbol of unity and friendship between two nations—two great republics.”

—Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, October 26, 1886

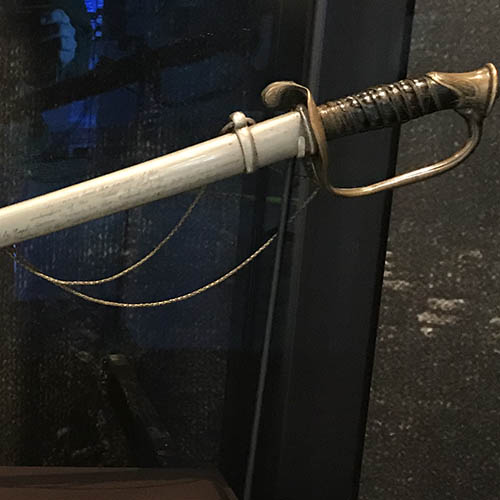

On opening day, a flotilla of ships, all decorated in red, white, and blue, formed a naval parade to Bedloe’s Island. Spectators aboard the vessels watched the French flag draping the colossal Statue’s face and anticipated the official unveiling. Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi himself was stationed in the crown, awaiting the signal to drop the flag at the end of the dedication ceremony. As he listened to patriotic tunes and the passionate speeches of distinguished guests on the ground below, he waited for a signal that the speeches had ended. His helper mistakenly gave the signal when one of the speakers paused, and Bartholdi unveiled the Statue’s face too soon, in the middle of a speech by Senator William M. Evarts, chair of the American Committee. Cannons thundered, brass bands roared, and steam whistles blew from hundreds of ships in the harbor, overpowering Evarts’ words. Their salutes welcomed the Statue of Liberty home.

A Momentous Day

The Statue’s unveiling was more than an occasion for celebrating; it was a time to honor the people who had created and paid for it. Expressions of gratitude were exchanged. Mainstream newspapers cheered the “great masses” gathered in the city streets to welcome the Statue and view the parade, and the sculptor, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, was hailed as the man of the day.

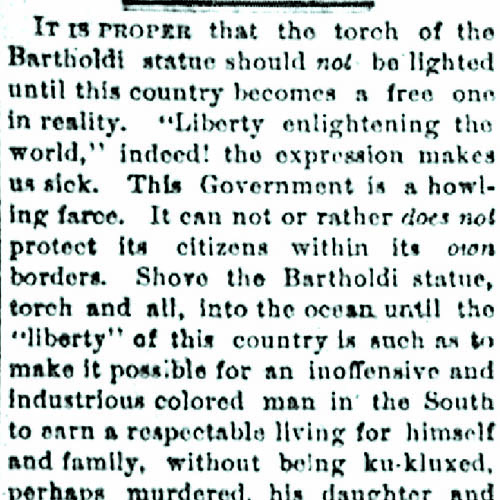

But for people in the United States with limited liberty, it was a day to call out the hypocrisy. Suffragists protesting during the opening ceremony objected to the use of a female figure to symbolize liberty when American women did not have the right to vote, and African American journalists expressed their ambivalence about the Statue in the wake of Reconstruction, signaling that its interpretation would become a cause for debate.