Embracing Liberty

In the more than a century since the Statue of Liberty’s dedication, its symbolism has expanded and become more complex. Laboulaye’s vision of the universal ideal of liberty blurred as global wars, waves of immigration, the forces of commercialization, and mass social movements led to new interpretations of liberty and of the Statue itself.

For many Americans, the Statue continues to represent an idea that is fundamental to their sense of identity as individuals and as a nation. Yet there is a continued tension between the declared commitment to liberty and the persistence of its unequal distribution in the United States and beyond. At times, the Statue represents strength and resilience. At other times, it is a reminder of injustice. The stories of the people who have used the Statue’s image for patriotism, protest, or profit reveal possible answers to the question, “What is liberty?” To many, the Statue represents the United States—its possibilities and its traditions. To others, it is a universal symbol of the continuing quest for liberty.

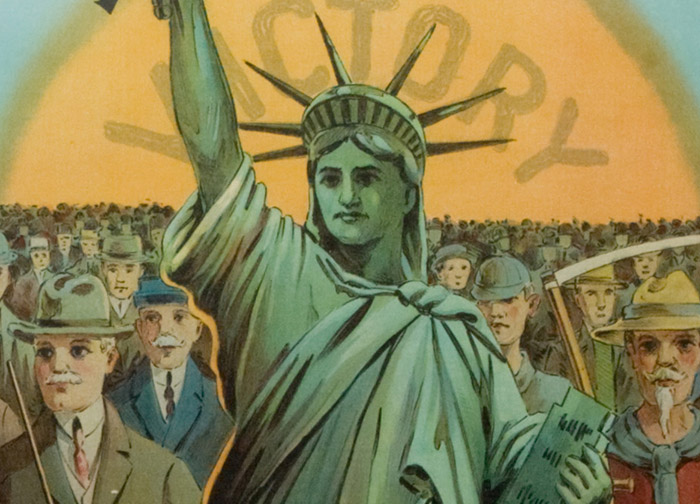

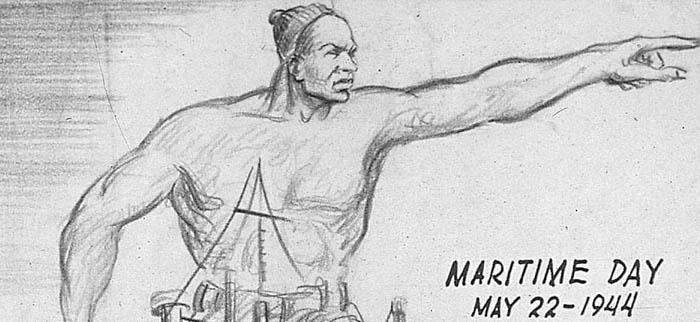

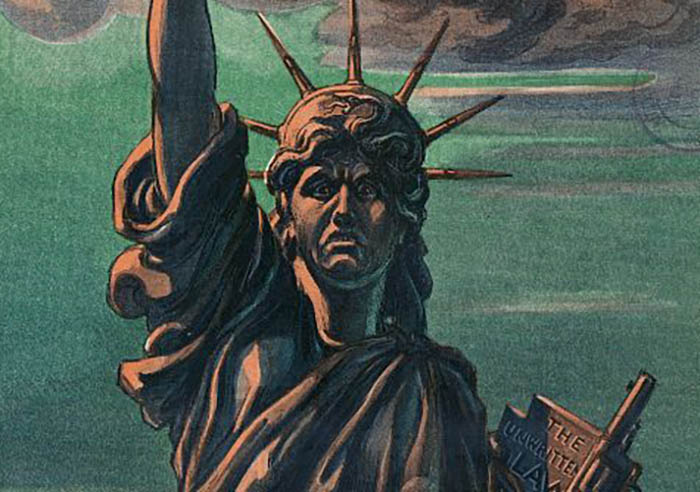

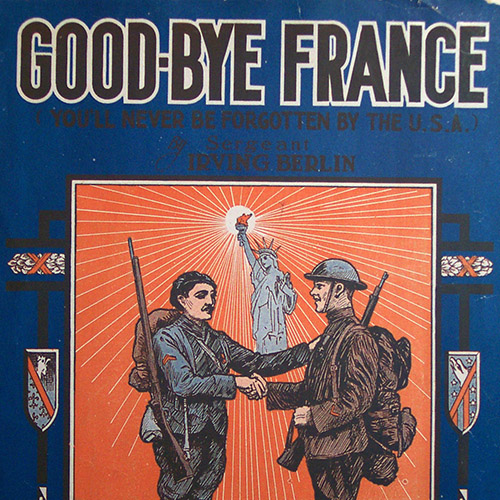

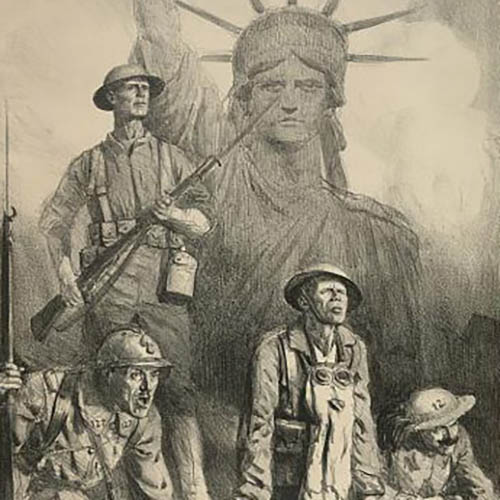

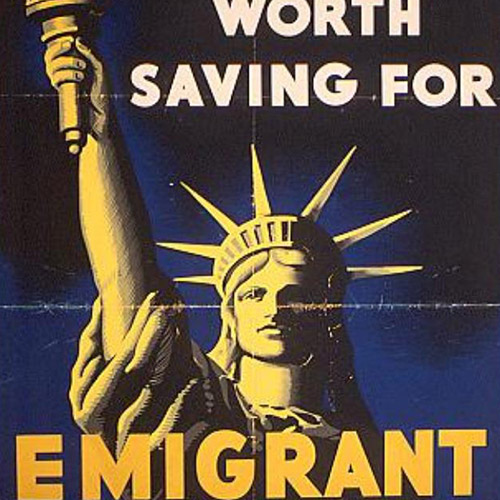

Mobilizing Liberty

During the First and Second World Wars in the first half of the 20th century, the Statue of Liberty was used to galvanize support for the war efforts. Images of the Statue—sometimes militaristic, sometimes maternal—appeared on wartime posters to encourage Americans to enlist, buy war bonds, and conserve resources. Wartime propaganda promoted the Statue as an American icon, presenting a vision of freedom and democracy to a world struggling against oppression and dictatorships.

Liberty in Conflict

Wartime promotion of patriotism in the United States has often occurred at the expense of racial and ethnic inclusion and at a cost to civil liberties. President Franklin Roosevelt’s address during the Statue of Liberty’s fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1936 referenced the Statue’s importance as a symbol of welcome to immigrants. Critics of the speech, however, could point to the fact that the isolationist mood of the country between the two World Wars had resulted in severe restrictions on immigration.

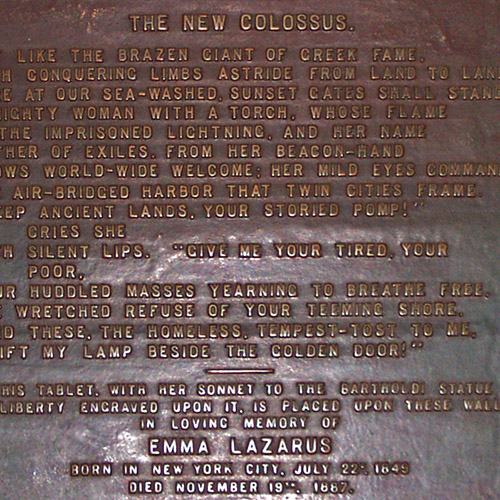

Mother of Exiles

From 1886 to 1924, approximately 18 million immigrants entered the United States through New York. As they entered New York Harbor, they looked up and saw the Statue of Liberty. To many of these new arrivals, the Statue’s uplifted torch did not suggest its creators’ intention of “enlightenment.” Rather, they saw it as a sign of welcome, promising opportunity and freedom from oppression. The colossus soon became an icon of immigration.

But for those people who have felt unwelcome or have been turned away, the Statue’s image reflects intolerance, exclusion, and unfulfilled promises. Whether portrayed as a welcoming mother or a strict gatekeeper, the Statue remains an expression of the immigrant experience.

A Universal Icon

Laboulaye could not have imagined the mass appeal the majestic Liberty Enlightening the World would have in popular culture or how its symbolism would be compromised by commercial use and wide circulation. The Statue’s image was exploited even before its construction began. Bartholdi himself licensed it to advertisers to support fundraising efforts.

Since then, the Statue’s likeness has become ever-present, spawning souvenirs and keepsakes of every imaginable variety. For over 100 years, advertisers, artists, and filmmakers have manipulated this renowned work of art and used the Statue as a “stand-in” for the United States, New York City, democracy, immigration, and various cultural products. Employed in these ways, the Statue of Liberty remains one of the world’s most evocative icons, used to inspire, entertain, and profit.

Continued Quest for Liberty

The Statue of Liberty was originally conceived in part to celebrate the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States. For many around the world, the advancement of freedom is the monument’s most important symbolism. Ordinary people, from American suffragists in the 1800s and 1900s to Chinese students in the 1980s, have raised up the Statue’s likeness to call for greater equality, an end to injustice, and more enlightened societies.

In the ongoing struggle for these causes, the Statue’s image can convey hope and encouragement, but it can also be a bitter symbol for promises unfulfilled. From the patriot to the refugee, the dissident to the disenfranchised, many who seek liberty continue to look to the Statue. For all those who quest for liberty, the Statue continues to beckon, challenge, and inspire.