Mrs. Walker’s involvement in social activism and politics is evident in her personal papers. Her voluminous notes, meeting minutes, monthly journals, and correspondence relating to her work in various organizations reflect a commitment to gender equality, racial uplift and economic empowerment.

She was a member of countless organizations and sat on many of their boards of directors or trustees. In addition to heading the IOSL, Mrs. Walker was a leader in the National Association for the Advancement of Color People (NAACP), National Association of Colored Women, National Association of Wage Earners, Council of Colored Women, Interracial Commission, National Negro Business League, Negro Organization Society, and others. Her community activism aimed towards gaining equality and opportunity for African Americans while demonstrating the abundance of intelligence, business savvy, and determination in black communities. More...

Mrs. Walker accomplished much in achieving African American empowerment. Her remarkable public speaking allowed her to effectively reached out to people. Walker traveled the nation far and wide, imparting inspiring messages for people at conventions and meetings. She spoke bluntly and charismatically about the evils of Jim Crow and the responsibilities African Americans had to take on to uplift themselves. At one of her 1902 public addresses an onlooker described the scene. “For fifteen minutes or more, such a speech, persuasive, musical, and eloquent fell from her lips, as she called upon the black men of Virginia to stand up for their rights, to fight slavery, to live for their children and for hers, caused old men and young men to weep.”

The culmination of this public prowess occurred when in 1921, Mrs. Walker ran for public office — the first woman in Virginia to do so. Because of her considerable work, she had respect of, and standing in both the black and white communities in Richmond. Mrs. Walker's ability to appeal to diverse audiences made her a worthy candidate for Superintendent of Virginia’s Public Schools on the “Black Lily” ticket. A sample ballot from 1921 shows her name along with prominent African American Virginians, John Mitchell (ran for governor) and Thomas Newsome(ran for secretary of state). Walker was able to connect with prospective voters by tirelessly campaigning using her oratory eloquence across Virginia. She received 20,000 votes as compared to Mitchell’s 5,000 votes. Her diligent efforts and her appeal to the recently suffraged women in Virginia probably increased her votes.

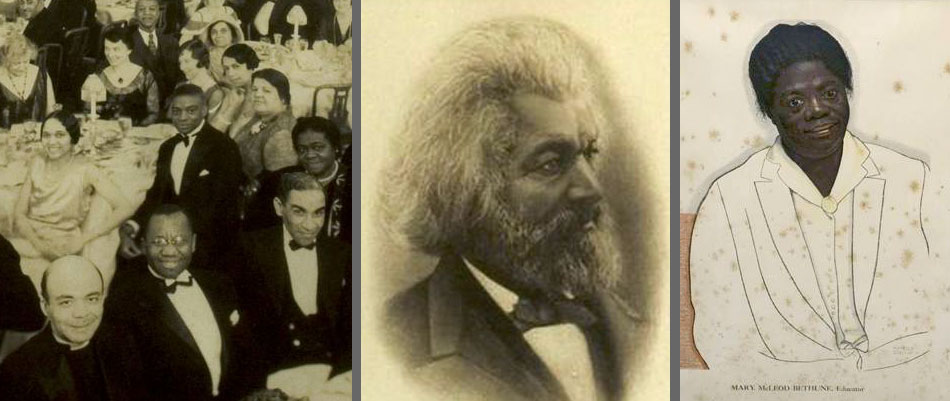

Maggie L. Walker was extremely passionate about African American and particularly African American women’s uplift. During her lifetime, she saw ongoing misogyny and racism in the Black Code and Jim Crow laws. As she led the Independent Order of St. Luke, Mrs. Walker purposefully employed black women whenever possible. The Order’s executive board consistently reflected the female constituency She surrounded herself with talented, determined African American women such as Mary McLeod Bethune, Nannie Helen Burroughs and Janie Porter Barrett. She donated heavily to African American schools from the elementary to university levels, especially schools for girls. Her aim was to ensure that black men and women would have the same professional opportunities; that black girls could dream of careers outside of teaching and housework and be able to realize those dreams. At Walker’s tribute for her 25th anniversary as the IOSL’s Secretary-Treasurer, Dr. Bessie Tharps described that one of Walker’s accomplishments was “to see as a result of her leadership, her dark sisters sitting like women of other races in finely equipped offices, with working hours like those of other fine women, and a pay envelope of which none need be ashamed….”

Even as Mrs. Walker aged and her health declined, her work continued. She worked well with community leaders across color lines, but fought hard to ensure professional employment and higher socioeconomic status for members of her race. At times she faced opposition from African Americans. In a 1932 Board of Directors of the Industrial Schools meeting, fellow board members wanted to hire white doctors and bookkeepers for the all black schools. At the next meeting Walker came with an entourage of black doctors, lawyers and other professionals to speak against such an action. The presentation had no effect on the board’s opinion, but is an example of the lengths to which Walker would go to fight for African American equality.

Walker was also committed to African American education. She often spoke of education as a means of total liberation for African Americans, but also warned against the sense of privilege and classism that it could instill. In her 1909 “Race Unity” speech, Walker chastised the “women and men who write beautiful essays and make grand speeches,” but “generally practice about as little what they preach as a doctor takes of the medicine which he prescribes.” She firmly believed, though, as she stated that day, “If we are to have race unity it must be largely the work of the school house and the church.” She put her money to work and donated to local and regional schools to ensure the continuation of education initiatives for black children. During the Great Depression, Walker continued to support St. Luke youth and local education. She founded the Council of Colored Women to raise money to start the Janie Porter Barrett’s Industrial Home School for Girls in Peake, Virginia.