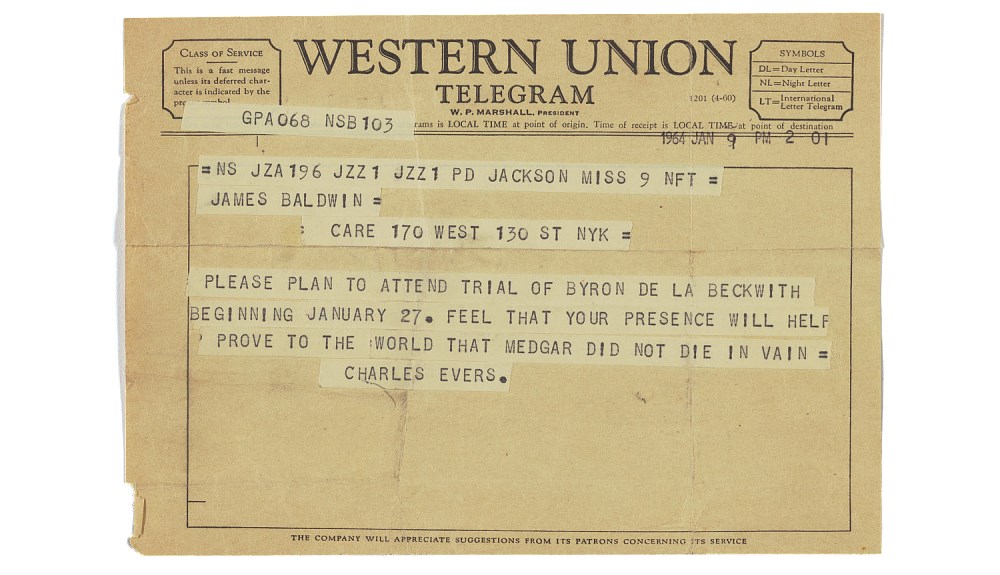

James Baldwin Collection, National Museum of African American History and Culture Medgar’s murder investigation was brief but successful. Within hours, police had the murder weapon, fingerprints, and a suspect. Then why did it take three decades to put the killer behind bars? InvestigationA hidden gunman shot Medgar Evers at his home just after midnight on June 12, 1963. Neighbors, patrons of a nearby diner, and his own family all testified to hearing the shot. Jackson Police arrived within minutes. While some officers escorted Evers to the hospital, others began looking for information. There was plenty to find. The bullet had passed through Medgar’s body, broke a window, passed through a wall, and ricocheted off the refrigerator before coming to rest on the kitchen counter. Investigators traced its path to determine where the shot originated. In a clump of bushes approximately 200 feet from the house, they found recent disturbance, a broken limb. In the light of morning, they found a recently-fired rifle, purposefully hidden in a tangle of vines. It matched the bullet and bore fingerprints. The fingerprints matched those on a United States Marine Corp card for Byron De La Beckwith, who lived in Greenwood, Mississippi. Police arrested Beckwith on June 23. 1964 MistrialsAll signs pointed to Beckwith. Ballistics confirmed the murder weapon, which held fingerprints; multiple eye witnesses placed Beckwith’s car in Jackson that fateful night; a Jackson cab driver had even spoken to Beckwith specifically about Medgar Evers. Plus, Beckwith’s segregationist views and commentary on President Kennedy and the NAACP were well known (and well documented). He was a member of the White Citizens’ Council, a segregationist group that produced racist propaganda with thinly-veiled calls for violence. A grand jury indicted Beckwith in July 1963. The state tried him for murder in 1964. Despite the evidence, the trial proved difficult. The atmosphere in 1960s Mississippi was fraught. Racial prejudice ran deep. Beckwith produced three witnesses that provided him an alibi. With the all-white, all-male jury unable to reach a verdict (called a “hung jury”), the judge declared a mistrial. A second trial was held, but to the same end. Another hung jury. Beckwith posted bail and went free. 1994 TrialMyrlie Evers-Williams never gave up her search for justice. In 1990, new information came to light: Files of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, an arm of the state government dissolved in the 1970s, had secretly aided Beckwith's defense attorneys during the earlier trials. With pressure from Myrlie and the local press, this new evidence meant a new trial. In addition to the old evidence and testimony, new witnesses came forward. Some testified that Beckwith openly bragged about killing Evers. In February 1994, a (mixed-race) jury convicted and sentenced Beckwith to life in prison. Further ReadingNational Archives News article: Journalist Shares Stories Behind Civil Rights Cold Cases |

Last updated: June 13, 2022