|

In 1855, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his most popular poem, The Song of Hiawatha. It was an immediate success, propelling Longfellow into literary stardom and influencing popular culture for decades to come. In this epic work, Longfellow set out to honor Native American heritage, but simultaneously perpetuated stereotypes and the false assertion that Indigenous culture was dying in America. Since then, the merits and pitfalls of Hiawatha have been rightly debated as its hold on American culture endures.

Longfellow used rhythmic poetry to convey various Native American myths to a popular audience. Primarily, the epic poem highlights the stories of the Ojibwe people of the Lake Superior region. Its main focuses are the adventures of a fictional Ojibwe hero, Hiawatha, his gifts to his people, and his tragic love story with a Dakota woman, Minnehaha. Before Hiawatha’s arrival, the reader enjoys various interwoven scenes, such as the case of the personified South Wind, Shawondasee, falling in love with a dandelion he takes to be a golden-haired young woman. Later, Hiawatha’s grandmother falls from the moon, and he is eventually born. The poem traces his life from childhood adventure, falling in fast love with Minnehaha, marrying, and losing her from illness. In the end, he leaves after white settlers arrive, feeling his time has passed and that his people will manage. Before this ending, Hiawatha defeats malevolent gods, and gifts his people with greater crop yields, and the invention of reading and writing. Longfellow’s poem was much more than a retelling of traditional Ojibwe tales for a white audience. His intent, born out in his creation, was to mold Christian values, European literary structure and Native American culture into a single great “American” epic to rival those of the European classics. In so doing, Longfellow brought positive attention to the Ojibwe people and helped spur the preservation of some elements of their culture. However, he also Europeanized their legends and assimilated their culture into the American mainstream. Because of this, Hiawatha has a complicated legacy that has impacted perceptions of Native Americans in this country for over 165 years.

NPS photo, LONG Collection Creating an American EpicBefore beginning his career as a respected college professor, and long before he became “America’s poet,” Longfellow traveled extensively in Europe. Through the languages and literature he absorbed, he came to feel that any nation’s identity should be one with its written word. This fueled his hope for a distinct national literature for the United States, still a relatively young nation seeking cultural independence from its estranged parent country. Criticism for HiawathaThe most popular and contemporary literary critiques of The Song of Hiawatha were focused on its poetic meter (tetrameter, or eight syllables in each line), and the accusation that some of its myths were lifted from a Finnish epic, The Kalevala. To the assertions that he used tetrameter in imitation of The Kalevala, Longfellow defended his decision and stated that the style was not exclusively Finnish. In light of his reliance on scholar Henry Schoolcraft, it is of little surprise that Longfellow would choose the form. In the introduction to one of his own poems, Schoolcraft suggested, “The measure (tetrameter) is thought to be not ill-adapted to the Indian mode of enunciation. Nothing is more characteristic of their harangues (aggressive lectures) and public speeches.”4 It has, in fact, been determined that the majority of Native American narrative poems from 1790 to 1849 contained mostly tetrameter.5

NPS Photo, Longfellow Family Photograph Collection, LONG Collections However, not all the divergences between Hiawatha and Ojibwe legend can be chalked up to Schoolcraft. Some plot points were wholly invented by Longfellow. One prominent example is the romance between Hiawatha and Minnehaha. Not only was there no such point in Schoolcraft, nor indeed in any Anishinaabe legends, but it was at odds with the structure of Anishinaabe familial life. Anishinaabe families relied on commonly recognized relationships, akin to common-law marriages, rather than formal, licensed marriages. This was regularly a cause of angst for white Americans seeking to Anglicize Native American groups, whether they were official government “Indian” offices or missionaries. The formal wooing and wedding plot in Hiawatha was a thoroughly European story dressed in the costumes of Native Americans. Another mistake of Longfellow’s concerns the central character, Hiawatha. Longfellow noted in his journal in June of 1854 that he began “Manabozho's first adventure.”9 Manabozho, or Nanabozho, a trickster spirit who was a cultural hero in Ojibwe legend, was Longfellow’s basis for his hero. By the very next day, though, Longfellow wrote that he was working on “’Manflbozho;’ [sic] or, as I think I shall call it, ‘Hiawatha,’-- that being another name for the same Manito.”10 This is a mistake. Hiawatha was not another name for the Ojibwe trickster, but rather a 16th century Iroquois leader, renowned in his own right. The true Hiawatha, who aided peace and cooperation among the Iroquois tribes, has had his identity overshadowed by the renown of Longfellow’s poem. Longfellow’s editorial discretion goes beyond his naming mix-up. Ojibwe writer and academic Gerald Vizenor explains that Manabozho “represents a spiritual balance in a comic drama rather than the romantic elimination of human contradictions and evil." Longfellow sanitized the essential “trickster” nature of Manabozho, transforming him into an “isolated and sentimental tragic hero” rather than the complex figure of Ojibwe legend.11 This is perhaps most evident in the closing of the poem. Hiawatha welcomes the white missionaries who arrive, and urges his people not only to welcome them, but to follow their lead:

This scene is not from Schoolcraft, and instead is entirely Longfellow’s creation. By attaching the Anishinaabe legends to the arrival of white settlers, Longfellow built a seamless lineage connecting his American cultural hero to the expansion of white settlements in the country.

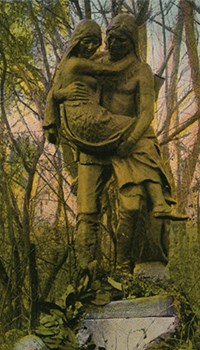

Metropolitan Museum of Art Hiawatha’s Success and Art InfluenceThe Song of Hiawatha was an instant success for Longfellow, becoming one of his most successful published works and arguably one of the most influential poems of the century. This was an era of the “vanishing Indian” stereotype – the idea that Native Americans would inevitably disappear where legislation and education were actively eradicating Indigenous culture. However, Hiawatha sparked widespread interest in Indigenous culture. Shortly after the publication of Hiawatha, numerous artists began to create music, sculptures, lithographs, and more inspired by Longfellow’s story, depicting Indigenous people culture. Most of these creative works were ultimately very European in nature, but still signify the cultural significance that Hiawatha had on the general public. Shortly after the publication of Hiawatha, the composer Robert August Stoepel worked directly with Longfellow to produce Hiawatha: A Romantic Symphony. In his journal, Longfellow wrote that the music was, “beautiful and striking; particularly the wilder parts.” From 1898-1900, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor composed the three-part cantata, Hiawatha’s Wedding, The Death of Minnehaha, and Hiawatha’s Departure. This interest in Hiawatha-inspired music continued into the 20th century and into popular music as well with Neil Moret’s “Hiawatha" published in 1901. While composed in a manner traditional to European customs, features of Hiawatha had a significant impact on music, and future generations would continue to use this as a foundation to continue experimenting with Indigenous influence.12 Hiawatha was also a significant inspiration for the fine arts. One notable collection is the sculptures created by Edmonia Lewis, a woman of Black and Indigenous descent who spoke of her mother being Ojibwe. Lewis’s works, like others, were created in a European, neoclassical style. She created two busts (one of Hiawatha and one of Minnehaha) and three other sculptures depicting scenes from the poem. In 1872 the famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens created Hiawatha, a full-body sculpture of Hiawatha thinking in the forest. Other artists who created paintings inspired by Hiawatha include Thomas Eakins, Thomas Moran, and Albert Bierstadt. Furthermore, Currier & Ives, known for their picturesque wintery scenes, also created and sold lithographs depicting scenes from Hiawatha despite it being uncommon for them to sell scenes from literature.13 Hiawatha's Implications for Native AmericansWhen examining the impact that the poem has had on Native Americans as a whole, it is important to look at both the past and the present, the positive and the negative. Longfellow wrote in his journal, “I have at length hit upon a plan for a poem on the American Indians... It is to weave together their beautiful traditions into a whole.” In another statement, he again showed reverence, but it was accompanied by acceptance of the prevailing narrative of a dying Native American culture. For him, it was a hallowed heritage:

This relegation to the past served the poem’s main purpose: creating a classic American hero. But while the Hiawatha of the poem became a beloved character for nineteenth century white Americans, he also encourages his people to embrace the white missionaries’ message just before he leaves to travel west at the end of the poem.

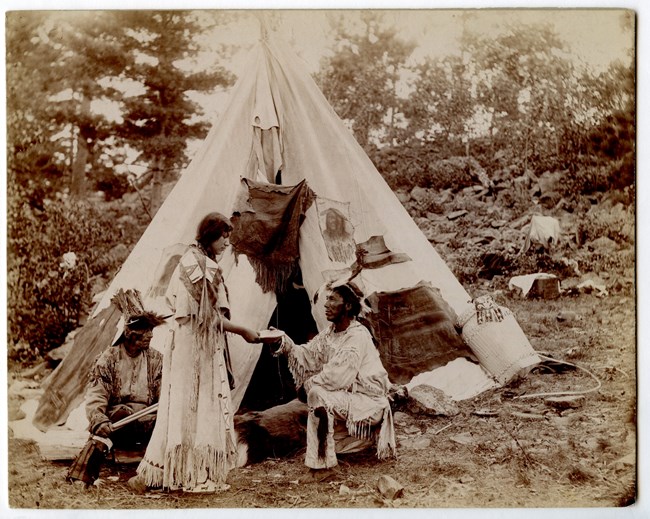

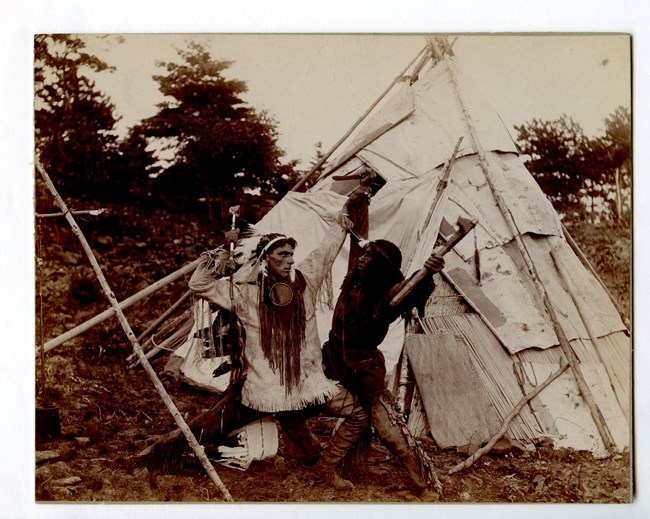

NPS Photo, Longfellow Family Photograph Collection, LONG Collections Despite this problematic message, the culture surrounding native reenactments of The Song of Hiawatha enabled the Anishinaabe to reclaim their customs represented in the poem and benefit financially from it. While adaptations by white casts were popular for decades after publication, the 1880s brought all-Native casts onto the scene. In 1899, Ketegaunseebee Anishinaabe actors in Ontario, Canada were funded by the Canadian Pacific Railroad to put on a Hiawatha performance that began a tradition of annual performances (pageants). In 1901, the surviving Longfellow children were invited to Ontario to experience the Hiawatha pageant inspired by their father’s creation. The Longfellows received an invitation written on birch bark inscribed with the following:

Despite the Railroad’s intention to profit off of Indigenous efforts, these pageants provided a unique opportunity for the Anishinaabe people to literally rewrite The Song of Hiawatha to better represent their culture and traditions. For the Ketegaunseebee Anishinaabe, they published their script and titled it, Hiawatha, or Nanabozho: An Ojibway Indian Play, to pay homage to the original character that inspired Longfellow’s Hiawatha.16 In addition, performing these pageants often allowed Anishinaabe actors to skirt government regulations surrounding their drumming and singing, serving as an important cultural connector within Anishinaabe communities. Across different Anishinaabe peoples, the practice also boosted local Indigenous economies. The prevalence of these pageants has waned in recent years. While Hiawatha pageants proved to have a positive impact on the Ojibwe people, the “vanishing Indian” stereotype demonstrated at the end of The Song of Hiawatha was utilized by American society to justify the eradication of Indigenous culture. No place demonstrated this aspect of Hiawatha's legacy more obviously than Indian boarding schools where "playing Indian" in school plays was among the methods of assimilation utilized to strip young Native Americans of their culture. Boarding schools would put on plays such as “Hiawatha” or “Pocahontas,” or stories created by staff, that demonstrated Indigenous people supporting assimilation.17 Furthermore, the role of Indian boarding schools in making the “vanishing Indian” stereotype a reality goes beyond Hiawatha in the Longfellow family’s history. Alice Longfellow actively contributed funds to the Indian School at Hampton Institute which educated Native American youth. Alice would receive letters from the youth enrolled at the school, often writing about their lives and their thoughts on Indian schools and Anglicization. Many students spoke highly of receiving an education, however, others, such as Pierrepont Alford, spoke of the difficulties. Once, Alford wrote to Alice about his father, saying that “when he [Thomas Alford] first left Hampton. The Indians did not have any thing to do with him. They said that he was not loyal to the tribe.” The letters Alice received reflect the complex legacy of institutions like the Indian School at Hampton Institute and the Longfellows' patronage to them.

NPS Photo, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana papers, LONG Collections Today, The Song of Hiawatha is valuable for both its strengths and weaknesses. There has been much valid criticism over the fact that the poem contributed to the idea that Native American culture would, and should, soon vanish. Instead, Indigenous cultures endure and thrive. At the same time, Longfellow created the first major piece of popular culture in which Native Americans were portrayed in a heroic light, rather than a patronizing or outright negative one. At least one hundred places names inspired by the poem are in the languages of Algonquian and Siouan,18 a small form of preservation. Rather than placingThe Song of Hiawatha into a single binary category of “good” or “bad,” the poem merits a nuanced evaluation mirroring the Anishinaabe trickster Manabozho: “holding both good and bad, sacred and profane, mischief and honor, in tension.”19 NotesThe full text of The Song of Hiawatha is available on the Maine Historical Society's Longfellow poetry database.

|

Last updated: September 30, 2024