Defining the Underground RailroadThe Underground Railroad—the resistance to enslavement through escape and flight, through the end of the Civil War—refers to the efforts of enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom by escaping bondage. Wherever slavery existed, there were efforts to escape, at first, to maroon communities in rugged terrain away from settled areas, and later across state and international borders. Acts of self-emancipation made runaways ”fugitives” according to the laws of the times, though in retrospect, “freedom seeker” seems a more accurate description. While most began and completed their journeys unassisted, each subsequent decade in which slavery was legal in the United States saw an increase in active efforts to assist escape. The decision to assist a freedom seeker may have been spontaneous. However, in some places, particularly after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Underground Railroad was deliberate and organized. Freedom seekers went in many directions – Canada, Mexico, West, the Caribbean islands and Europe.

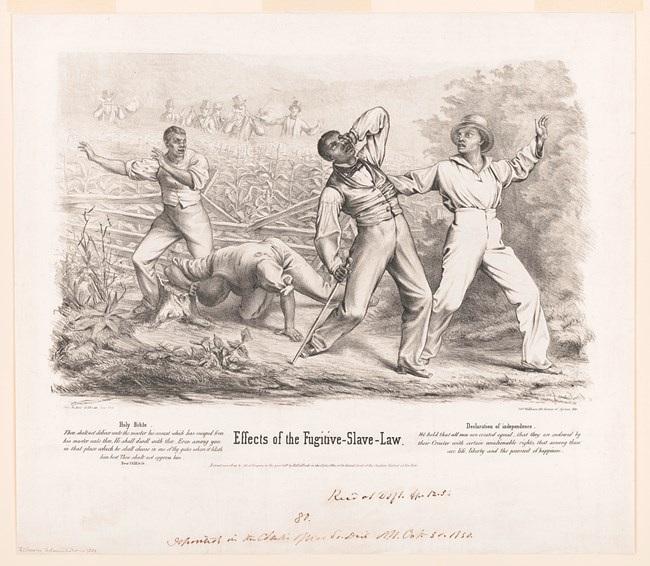

Library of Congress The Fugitive Slave ActsUntil the end of the Civil War, enslavement was legal in the United States. In contrast to Revolutionary War era rhetoric about freedom, the new United States constitution protected the rights of individuals to own and enslave other people. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 also enforced these slaveholding rights, providing for the return to enslavement of any African American accused or even suspected of being a freedom seeker. Denied access to an attorney or a jury trial, a freedom seeker faced any white person making an oral claim of ownership to a magistrate. Those who assisted the freedom seeker, or merely interfered with an arrest, faced a $500 fine, a clear acknowledgement of the impact of the Underground Railroad phenomena decades before it was given its name.

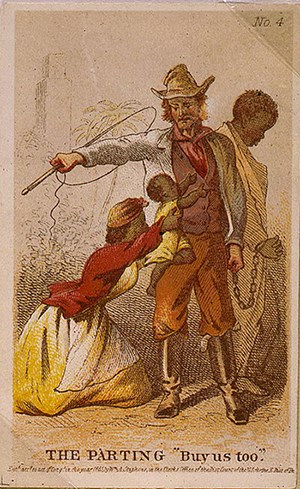

Library of Congress Motivation of Freedom SeekersConditions of enslavement varied in degree, based on time period, geographical area, the type of agriculture or industry, the size of the slaveholding unit, urban and rural environments, and even the temperament and financial stability of the enslaver. What is common to all of these experiences is the dehumanization of both the oppressed and the oppressor by the demands of a system that treate human beings as property. This factor, perhaps more than any other, explains why some people chose to flee and why often their owners expressed such surprise.

NPS Geography of the Underground RailroadWherever there were enslaved African Americans, there were people eager to escape. There was slavery in all original thirteen colonies, in Spanish California, Louisiana, and Florida, and on all of the Caribbean islands until the Haitian Revolution (1791- 1804) and British abolition of slavery (1834). Commemoration of Underground Railroad HistoryCommemoration is only possible once local Underground Railroad personages and events are identified. Primary sources, that is, period letters, court testimony, or newspaper articles are found to verify the history. The next steps are public education and preservation through protection of significant sites, and use of accurate history in heritage tourism, educational programs, museum and traveling exhibits, and commemoratory sculpture. Uncovering Underground Railroad HistoryDespite years of claims that Underground Railroad history was secret, local historians, genealogists, oral historians, and other researchers today find that there are primary sources describing the flight to freedom of many enslaved African Americans. Coming to light are court records, memoirs of conductors and freedom seekers, letters, runaway ads in newspapers, and military records which all testify to the determination of the enslaved to seek freedom for themselve and their families.

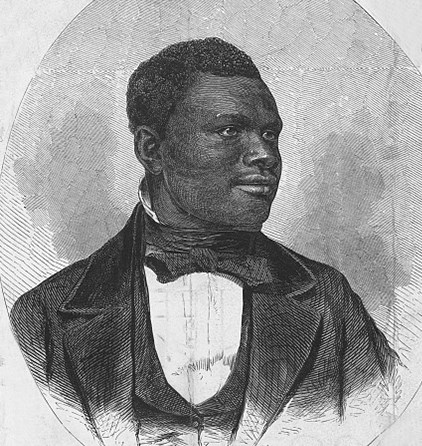

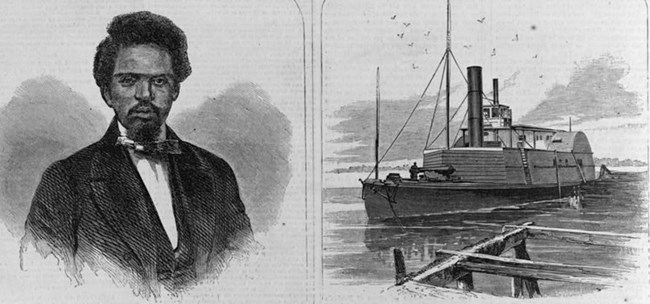

Library of Congress Unknown Underground Railroad HeroesUnderground Railroad is associated with Harriet Tubman, the “Moses of her people,” and Frederick Douglass, a freedom seeker who became the greatest African American leader of his time. Both came from Maryland. Freedom seekers, however, came from all places where the law supported enslavement, including the northern colonies. From North Carolina came Harriet Jacobs after seven years spent hiding in the attic of her grandmother. Sixteen- year old Caroline Quarles fled life as a house servant on a plantation in St. Louis and traveled 700 miles until she reached refuge in Canada. Anthony Burns stowed away on a ship in Richmond in order to attain a few years as a free man in Boston. Lewis Hayden, his wife, and child, escaped from slavery in Kentucky to Ohio with th help of Delia Webster and Calvin Fairbanks. In the middle of the Civil War, Robert Smalls and other black crew members of the Confederate ship the Planter sailed from its dock in Beaufort, South Carolina, to surrender to a Union flotilla. In California, black businesswoman Mary Ellen Pleasant sheltered runaway Archy Lee in her San Francisco home, leading to an important state court case.

Library of Congress Levi Coffin and John Rankin are known as white ministers, Midwestern conductors, who assisted freedom seekers. Based in Ripley, Ohio, freedom seeker John Parker helped numerous runaways to cross the Ohio River into free territory. Residents of Wellington and Oberlin, Ohio, both black and white, refused to let slave catchers take John Price back to enslavement in Kentucky. A biracial network in Washington, D.C., including Thomas Smallwood, Rev. Charles Torrey, Leonard Grimes, and Jacob Bigelow worked over years to help people such as Ann Marie Weems, the Edmondson sisters, and Garland White to seek freedom. Using a clever disguise, William and Ellen Craft escaped over one thousand miles from Georgia to Boston.

National Underground Railroad Network to FreedomThe National Park Service Underground Railroad program coordinates preservation and education efforts nationwide and integrates local historical places, museums, and interpretive programs associated with the Underground Railroad into a mosaic of community, regional, and national stories. The Network also serves to facilitate communication and between researchers and interested parties, and aid in the development of statewide organizations for preserving and researching Underground Railroad sites. Learn more and Explore |

Last updated: September 14, 2023