Alan Taylor, Pennsylvania State University Fire scars in tree rings provide a baseline for fire frequency in the early history of the Lassen region. People began suppressing fires in 1904 and over time this led to significantly longer fire cycles, increased forest densities, and changes in types of trees. In the 1980s the park began actively managing fire to help restore pre-suppression forest structure and composition and support the return of natural fire regimes (size, frequency, and intensity). Fire Frequency by Forest Type and ElevationForest composition changes with elevation, as the ranges of different tree species overlap. Researchers collected tree ring data from three forest types (elevations) on Prospect Peak, in the northeast corner of the park. Burn scars within each forest type provide a record of early fire history in which fire frequency decreased as elevation increased. Forests at higher elevation saw longer fire return intervals or number of years between fires. Increased snowpack and cooler temperatures at high elevation helps trees and ground fuels retain more moisture through the dry summer season. Decline in Fire Frequency after 1905Tree ring data from Prospect Peak shows a dramatic decline in fire frequency after 1905 in three forest types. The long intervals between fires in the 1900s resulted in major changes in forest condition.

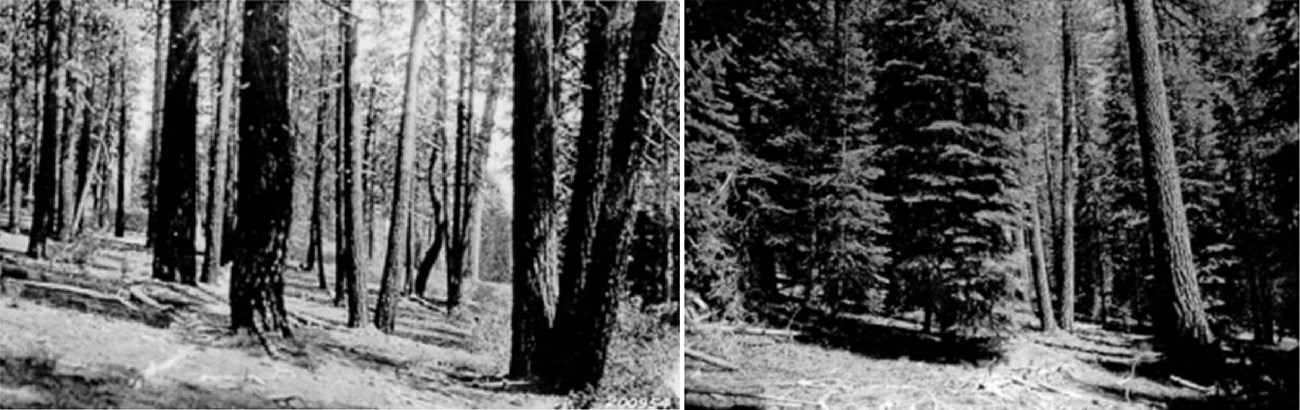

Left: A.E. Wieslander, 1925; Right: A.H. Taylor, 1993. Forest Change Following Fire SuppressionForest suppression efforts that began in 1905 have gradually resulted in changes in forest structure (proportions of different-aged trees) and composition (proportions of different species) in forests within the park. Low to Mid-Elevation: Increasing Density; White Fir Replacing Jeffrey PineWhite fir is a shade-tolerant species that can thrive in forests without regular fires. Jeffrey pine needs the sunny gaps in forest canopies that periodic fires create, where there is enough light for pines to establish and grow. See the repeat photo pair from the south side of Prospect Peak, illustrating the dramatic increase in tree density between 1925 and 1993 (Figure 2). High Elevation: Increased Density and Less Diverse StructureThe higher elevation Red Fir-Western White Pine forests experienced longer fire intervals due to moister, cooler conditions and more dense, less flammable ground fuels. Suppression has led to even less frequent occurrence of fire which is causing the forests to become more dense, with less variation in tree size classes. Fire History Data Inform Park ManagementThese fire history data inform the park’s fire management program by providing information on how often fire occurred in these different park forest types prior to fire suppression. This helps managers prioritize where it is most important to conduct prescribed burning or other actions, such as forest thinning. The information on changes in forest condition following fire suppression highlights forest types most in need of fuel reduction. Restoring forests to a healthier condition moderates effects of warming climate and future fires and protects wildlife habitat. ReferencesChappell, C. B. and J. K. Agee. 1996. Fire severity and tree seedling establishment in Abies magnifica forests, southern Cascades, Oregon. Ecological Applications 6: 628-640. |

Last updated: May 16, 2022