|

Welcome to Working Wednesday, where we'll be exploring the variety of occupations that kept the Keweenaw busy. Follow residents from their homes as they labor in mine or mill, store to salon, and many places in-between. We'll be hearing from the workers themselves using recordings from the park's oral history collection.

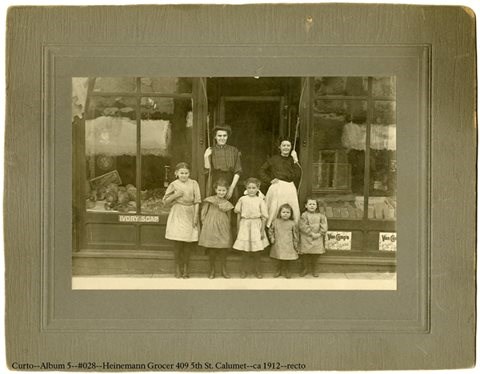

Historic image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Frank started working at the Quincy mine in 1924, when he was 16 years old. As Frank recalled, his father—a trammer at the Quincy mine—came home in the afternoon with some news: “‘You’re going to the doctor’s.’ I said ‘What for?’ He said, ‘You go to the doctor’s and if you pass, you’re going to work tonight.’ New employees began receiving physicals after Michigan passed a workers’ compensation law in 1912.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

After being declared fit for work, Frank got ready for his first shift underground—on nightshift. He had to borrow his father’s mining boots and carbide lamp, because the stores had all closed for the day by the time the doctor had cleared him, and he couldn’t buy his own. When asked how he felt about going to work in the mines, he said: “I just went in as if I worked there before. We used to hang around the mines so much I thought I worked there before! No, it did not scare us. When we had to ride down it was nice.”

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Mines were—and remain—dangerous places to work. Frank Shabal, his older brother Matt, and their father all worked underground in the Quincy mine. They were all working when their father suffered a fatal accident while unloading a tram car. As Frank recollected: “My dad died eight hours after he got hurt. He got hurt at five minutes after twelve. “My brother worked above and I worked below him on different levels and we did not know it until we got to the change house when the dry man—we called him the dry man that took care of the dry—told us, ‘hurry up and change. Go home, your father got hurt today.’ “Mind you, they did not let us know from 12:00 until 3:30. Yup.” Why do you think the managers failed to tell Frank and his brother about their father?

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

In 1940, Frank’s brother Matt would also die working underground at Quincy. When asked about their deaths, and accidents in the mine, Frank said: “It happened. Men meant nothing. You were just another animal. When somebody got killed years ago in the mine there, you would hear the whistle, not very loud, just a mourning [sound]…[and] somebody would run to the Captain’s office to ask for the job. Years ago, a man was just another number.” What do you think of Frank’s perspective?

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Mort Herstrom started as a laborer in the Kearsarge mine in 1953 before he was given a job mining. Like many kids, Mort moved to Detroit for work after graduating from Calumet High School. A few years later, he moved back to the Copper Country. He said: “When I came back up here….A lot of people wouldn’t dare go in the mine, but when I got in there, I liked it. I thought that was a great job, eight hours a day. Nice money. T-bone steaks every week. [laughs] It was good. I never regretted mining. That’s one part of my life I put in that I never regretted.”

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Barring loose rock was an important part of staying safe, particularly when copper lodes were being mined out. Workers needed to make sure that all the unstable rock in the mine was knocked down before miners went in to drill and blast for copper. Mort Herstrom explains a narrow escape at the Kearsarge mine north of Calumet, shortly after he started work as a laborer underground in 1953: “I can remember when I first started, they put me with an old man. His name was Frankovich. He was a miner, and... I was supposed to help him bar down the loose. I knew that it was going to come down pretty fast, and I told that old guy, I said, ‘Why don’t you go sit in the pillar hole [a safe place out of the way], because I’m able to move faster than you?’ Open Transcript Open Descriptive Transcript TranscriptAnd I had just touched this thing, and the whole thing came down. And I dove one way, dove out of there, and he was on the other side, and he was asking me if I was all right, he thought I was under it…he said boy, now, if that was him, he’d have been under it….[but] I was younger than him, and I figured well, I could move faster. But I just dove right out of there. That was one of the closest calls I had in the mine.

Descriptive TranscriptLogo shaped like an arrowhead. National Park Service. A sequoia tree towers over a bison with mountains and water in the background. A historic photo of miners wearing hard hats and carrying lunch pails riding a man car into the mine. And I had just touched this thing, and the whole thing came down. And I dove one way, dove out of there, and he was on the other side, and he was asking me if I was all right, he thought I was under it…he said boy, now, if that was him, he’d have been under it….[but] I was younger than him, and I figured well, I could move faster. But I just dove right out of there. That was one of the closest calls I had in the mine.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Two weeks ago, a young Mort Herstrom had just made sure that his elder coworker was out of harm’s way so he could start barring loose, unstable rock down to make the area safe for mining. “And I had just touched this thing, and the whole thing came down. And I dove one way, dove out of there, and he was on the other side, and he was asking me if I was all right, he thought I was under it…he said boy, now, if that was him, he’d have been under it….[but] I was younger than him, and I figured well, I could move faster. But I just dove right out of there. That was one of the closest calls I had in the mine.”

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

After Mort Herstrom was promoted from laborer to miner, he worked at a number of area mines, including Kearsarge, Centennial, and Osceola 13. He described a typical shift at the Kearsarge Mine: When you went down, usually, if you were a day shift, you went down at 7:00 and you knocked off for lunch at noon and you come up at 3:00. So, that’s eight hours a day, you worked. Probably if you were a miner, you probably drilled about maybe four and a half, five hours of that, and then you ate, and then you charged your holes, and hauled your powder up. These stopes were long stopes in Kearsarge, they were over two hundred feet. You had to haul your powder and your fuses and everything up. If you had a lot of holes, I mean, it was a lot of work. We used to do it. If anything broke, if your machine broke down, you had to go out and get another machine, haul that up. It was hard work, hard work. You sweat a lot. You got all wet from drilling. Rocks would be flying back at you. You were supposed to wear safety glasses, which most people did. We had hard-toe boots. You wore those, and a hard hat. You had that.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Like most other miners, Mort Herstrom chose to wear safety glasses and hard-toe boots while working underground. As loud as rock drills could be, however, he chose not to wear company-provided hearing protection like ear plugs. Why not?

Women have always been a vital part of the Copper Country economy. Although they didn’t work underground, by the late 1800s and early 1900s they worked in payroll, accounting, and other clerical departments. Many women operated boardinghouses, which meant managing finances, cooking, and doing the laundry for their own family and multiple boarders, most of whom worked for a mining company. Some were laundresses and domestics, hired to clean, cook, and provide childcare for other families. Many started their own businesses as seamstresses and milliners, or worked in a family grocery, jewelry store, or other commercial enterprise. Some even made extra money selling homemade wine and spirits. They also trained as midwives, nurses, teachers, librarians, and musicians

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Anne Caron Stafford and Melba Stafford Oja were mother and daughter, but had very different career paths. Anne, born in 1879, worked as a seamstress and bookkeeper until she got married. Melba, born in 1913, became one of Calumet’s most popular stylists. As Melba recalled, her mother attended a private school in Laurium to learn sewing and bookkeeping. One day, Anne and a coworker were on the second floor, looking out of one of the windows. They noticed a man walking down Oak Street in front of today’s Michigan House Cafe. |

Last updated: June 5, 2022