NPS / T. Fulton A Place of Magnanimous and Dynamic Change, Insistent in its Grandeur.Mountains tumble towards the coastal waters as black bears forage along the rocky beaches. Waves crash against rock. Harbor seals lounge in front of gargantuan tidewater glaciers that unleash ice into the ocean in thunderous calving events. Moving inland, tall swaths of lichen-shrouded spruce trees create a dense forest. Near the sharp peaks of the wilderness, mountain goats traverse the cliffs, and bald eagles soar above waterfalls. Kenai Fjords wilderness is a place of flamboyant beauty, and it is also a place of subtle power and delicate balance.

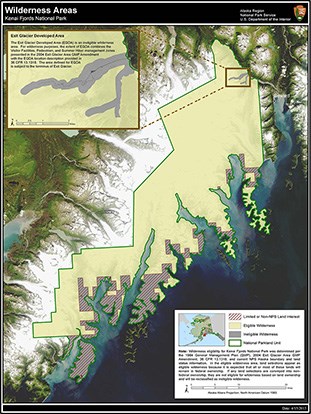

NPS Eligible WildernessKenai Fjords National Park encompasses over 569,600 acres of eligible wilderness, about 85% of the entire park. These eligible wilderness areas possess characteristics that reflect the definition of wilderness but require further study to determine if they should be recommended to Congress for wilderness designation.

NPS Photo/ A. Castellina Wilderness as HomelandSugpiaq people and villages maintain their cultural and ancestral affiliation to lands within park boundaries, including places of significance within wilderness. Sugpiaq (plural Sugpiat), means “real people." in their language Sugcestun. A maritime people, they span a large expanse of what is now south-central Alaska—including what comprises Kenai Fjords National Park. Alutiiq (plural Alutiit) is a term that stems from “Aleut.” Russian explorers used the name when encountering coastal Alaskans in the 1740s. The term Chugach refers to the Alaska Native people of the lower Kenai Peninsula, including lands within Kenai Fjords National Park, and Prince William Sound. Different individuals and generations use a mix of these terms to identify themselves. No matter the name, people past, present, and future are interwoven with these lands and waters.

A subsistence way of life is at the core of this relationship. While the federal lands of Kenai Fjords National Park are not designated for subsistence, subsistence practices occur on corporation-owned lands within the park and its adjacent waters. - Patrick Norman, President of Port Graham Corporation, 1997:23512a (uaf.edu)

NPS / J. Pfeiffenberger As glaciers retreat, they leave behind U-shaped valleys with steep slopes. Despite harsh weather and difficult terrain, microorganisms, mosses, and lichens establish themselves. New plants and animals move in, and shrubs and trees take root. A temperate rainforest supports a wide diversity of life. The Sugpiaq people harvest many essentials from the forest. They use wood to build the frames of traditional qayaqs (kayaks). Spruce roots provide materials for basketry and traditional hunting hats. Since time immemorial, people have been members of the community of life that inhabits these lands and waters.

NPS / F. North Visiting WildernessToday, Kenai Fjords provides opportunities to explore a plethora of human connections. We invite you to experience and appreciate the scenic and wild values of the Harding Icefields, its outflowing glaciers, coastal fjords, and wildlife and to comprehend environmental change in a human context. Kenai Fjords National Park has something for everyone. Whether you take a boat tour, go for a hike, or kayak in a remote fjord, you will be surrounded by exquisite scenery and abundant wildlife.Learn more about exploring Kenai Fjords wilderness. |

Last updated: June 12, 2025