In June 1912, Robert Fiske Griggs would have seemed an unlikely candidate to be affected by a volcanic eruption on the remote Alaska Peninsula. A professor of botany at the University of Ohio and devoted to his growing family, Griggs' professional and personal lives gave no hint a great legacy lay hidden in the aftermath of Novarupta's explosion on June 6th. Yet less than a year, later Griggs was on Kodiak Island on a request coming “out of a clear sky” to participate in a kelp study off the Alaskan coast. There he learned the 1912 eruption had buried the area in a foot of ash, and, sensing an scientific opportunity, began to study the eruption’s effects on the island’s vegetation.

In June 1912, Robert Fiske Griggs would have seemed an unlikely candidate to be affected by a volcanic eruption on the remote Alaska Peninsula. A professor of botany at the University of Ohio and devoted to his growing family, Griggs' professional and personal lives gave no hint a great legacy lay hidden in the aftermath of Novarupta's explosion on June 6th. Yet less than a year, later Griggs was on Kodiak Island on a request coming “out of a clear sky” to participate in a kelp study off the Alaskan coast. There he learned the 1912 eruption had buried the area in a foot of ash, and, sensing an scientific opportunity, began to study the eruption’s effects on the island’s vegetation.

He would return to Kodiak in 1915, continuing his research with a National Geographic Society grant and some reluctance. “I'd better take it,” he told his ailing wife Laura “It may be a stepping stone toward a trip to South America.” Instead it became a step beyond his life as a botanist, for he also made a short but fateful trip to the Katmai coast. Lacking enough rope to cross the Katmai River, Griggs' team turned back but not defeated. He would return, leading full-scale scientific expeditions to Katmai in 1916, 1917, and 1919. (An expedition did take place in 1918, but it was scaled back that year. Griggs did not go. Even his outsized determination couldn't overcome the United States' entry into World War I.)

It was on the 1916 expedition when Griggs made his most famous discovery: the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. On July 31st, he and D.B. Church crossed Katmai Pass. What they saw stunned them.

“The whole valley as far as the eye could reach,” Griggs would write later, “was full of hundreds, no thousands – literally, tens of thousands – of smokes curling up... we knew many of them must be gigantic. Some were sending up columns of steam which rose a thousand feet before dissolving.” The first glimpse into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes left Griggs sleepless. That night he turned over “the responsibilities and opportunities of our position” which “came over me in a flood of problems that I could not drop.”

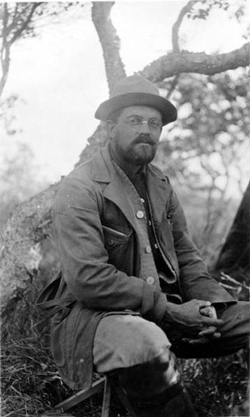

Griggs was understandably awed by the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. In his 1922 book, The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, Griggs captioned this photo with, “No photograph can convey more than a slight conception of the wonder and majesty of this sight as it first burst on our vision crossing the pass.”

The parallel between the Valley of 10,000 Smokes and Yellowstone struck Griggs immediately, and he feared his reports would be dismissed like Jim Bridger's description of Yellowstone. At the same time he recognized “the Katmai District must be made a great national park accessible to all the people,” a calling Griggs believed in deeply despite the “tremendous amount of effort” he knew it would require.

The Valley was a new world in every sense: an unexplored, uninhabited, isolated, unstable, steaming land almost beyond all previous human experience. Kodiak, the nearest town to the Katmai region, lay on the other side of the unpredictable Shelikof Strait. Supplies arriving from Kodiak had to be landed on the coast, then packed in by foot to base camps through miserable, and at times dangerous, weather. Freezing rivers full of pumice and dead trees wandered over thigh-deep mudflats peppered with quicksand. Boulders rolled off mountains in continuous waves—noisy reminders of the area's instability. At times the ground rang hollow under walking sticks, raising the specter of collapsing into an abyss. Savage winds destroyed tents, sent dishes flying, and lifted members off their feet. Worst of all, it carried blinding clouds of pumice which “cut like a knife whenever it struck our flesh.”

"The labor involved in such travel cannot be described, but must be experienced to be appreciated." Griggs, 1922.

The steam vents represented a danger as well, and at first they were sources of fear and wonder. With experience, the fear subsided. Griggs and his team learned these fumaroles could boil water, fry bacon, and bake bread. The expeditions discovered much else—a two-mile wide caldera, evidence massive floods and landslides, a “great incandescent sand flow” hundreds of feet deep covering 44 square miles, a steaming volcanic plug 200 feet high—but it was the fumaroles which captured everyone's attention. Griggs believed these would be the centerpiece of the “great national park,” and he described the steam vents at length in National Geographic articles and a 1922 book. Aware words alone could not do the fumaroles justice, expedition members captured them in both still photography and motion pictures; in 1919 Griggs even hired an acting crew to interact with them.

By that year the “tremendous amount of effort” had paid off. The previous September, President Woodrow Wilson had designated the Valley area as Katmai National Monument, partly because “its phenomena exist upon a scale of great magnitude, arousing emotions of wonder at the inspiring spectacles, thus affording inspiration to patriotism and the study of nature.” At roughly 1,700 square miles the monument was not as extensive as Griggs and the National Geographic Society had hoped, nor was it a park. It was a seed however, a large one, and over the years it would continue to grow.

The 1919 expedition was Griggs' last journey to Katmai. After it his life returned to its expected path; he went on to a distinguished career in botany and raised four children. From a distance he watched Katmai National Monument expand, and not merely in size. As monument's physical boundaries grew, so did its purpose. In time it evolved to protect Katmai's wildlife, habitats, histories, and wilderness as well as its volcanic heart. Eventually, though he would not live to see it, Katmai became the national park Griggs had always believed it should be.

Robert Fiske Griggs died on June 10th 1962, 50 years and one day after the Great Eruption of 1912 ended. His remains, as well as those of his beloved wife Laura and his son David, rest on Katmai National Park's second highest peak. Formerly known as Knife Peak, Mount Griggs is 7,602 feet high and just five feet shorter than Mount Dennison, the highest peak in Katmai. The location of the former Knife Peak is more than appropriate to honor Griggs' legacy: it stands watch over the Valley of 10,000 Smokes.![]()

Knife Peak was renamed Mount Griggs in 1956 to honor the legacy of Robert F. Griggs. NPS/M. Fitz

![]()