Landscape detectives

After looking at some maps of the estate and former Sexton Tract, a few of the rangers here at the Vanderbilt Mansion NHS decided to play detective. Our question was: does any evidence remain on the landscape from the time when the Sexton Tract was separated from the Hyde Park estate?

Aerial view of Vanderbilt Mansion NHS (Google Maps)

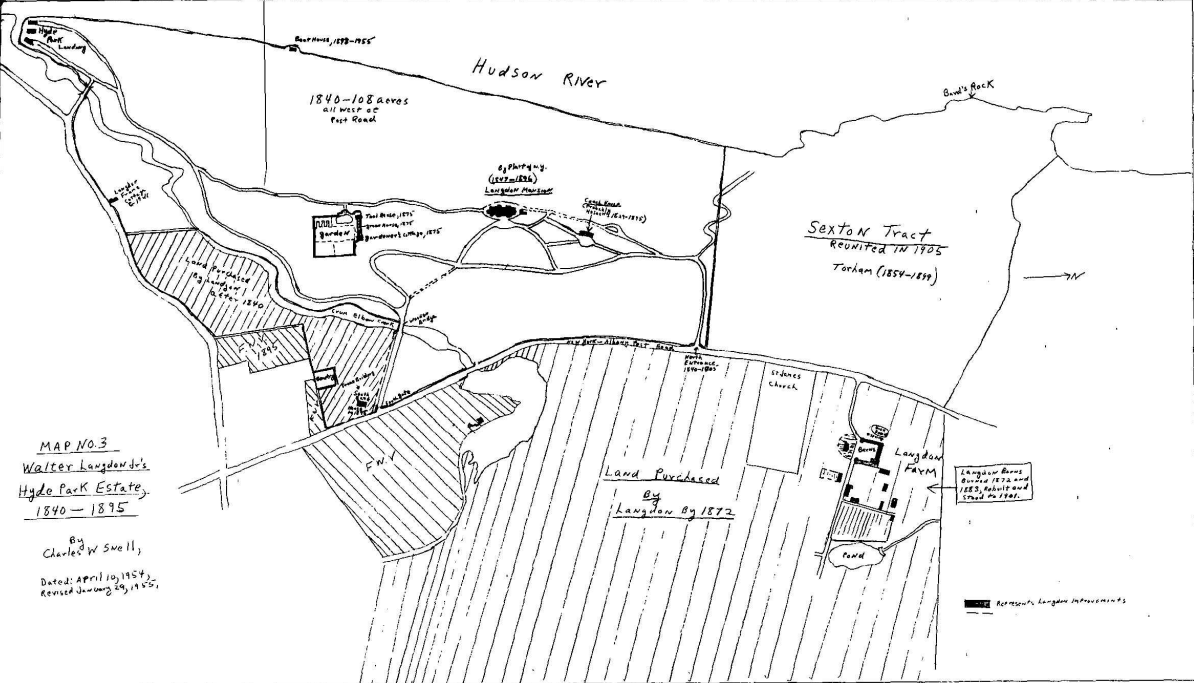

To answer this question, we headed out to the north field. Our sleuthing first led us among the white pines to see if the stone wall that borders U.S. Route 9 bore any signs of the reconfiguration of the driveway that Vanderbilt made after he purchased the Sexton Tract in 1905. Prior to that change, a driveway ran across the north field, jutting out toward Route 9 (the Albany Post Road) just south of where the overlook is today. We couldn’t see any evidence of changes to the outer stone wall that would indicate there was once an opening in it for this driveway. However, we think that the location of the driveway is still visible on the landscape. A flat, slightly raised section of ground cuts across the field, near the overlook. It lines up pretty well with the location of the old driveway on historic maps of the estate.

Map of the estate showing the layout of the property around the time Vanderbilt purchased it from the Langdon family, including the former driveway configurations. (Cultural Landscape Report for Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, Vol. 1. 1992.)

Map of the estate showing the layout of the property around the time Vanderbilt purchased it from the Langdon family, including the former driveway configurations. (Cultural Landscape Report for Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, Vol. 1. 1992.)

The stone wall that runs along the Albany Post Road (U.S. Route 9), facing east. This wall bore no signs of a change in the estate's exit driveway reconfiguration that occured after Vanderbilt purchased the property in 1905. (NPS photo)

Though faint, evidence of the former exit drive still exists on the landscape today. (NPS Photo)

Though faint, evidence of the former exit drive still exists on the landscape today. (NPS Photo)

Ranger Will stands to the south (left) of the location of the Vanderbilt estate's former exit drive. (NPS photo)

Ranger Will stands to the south (left) of the location of the Vanderbilt estate's former exit drive. (NPS photo)From what we could see, no evidence remains of the tract’s main residence, which would have been just east or south east of today’s overlook (a pretty incredible spot for a house!). Evidence of outbuildings was just as illusive.

The likely spot of the Sexton Tract's main residence. This is just across from the overlook of the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains. (NPS photo)

The likely spot of the Sexton Tract's main residence. This is just across from the overlook of the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains. (NPS photo)

Ranger Will points toward the probable location of the Sexton Tract's main residence. (NPS photo)

The spectacular view of the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains from the overlook at Vanderbilt Mansion NHS. The view from the Sexton Tract's main residence would have been similar to this. (NPS photo)

Down at Bard Rock, however, one small element remains from that section of the property’s long history of boating and shipping: a boat hook. Since the Vanderbilt’s retained the Sexton boathouse when they acquired Bard Rock, this hook may be the most obvious remnant of the Sexton ownership. This hook was what brought the smaller vessels in and out of the water, which the Vanderbilts would use to access their yacht.

The boat hook at Bard Rock. (NPS Photo)

The boat hook at Bard Rock. (NPS Photo)

A Brief History of the Sexton Tract

Though the Sexton Tract was not part of the estate that Frederick Vanderbilt purchased in 1895, historically it had been. Original estate owner John Bard inherited 3,600 acres in 1764 that included the acreage that Vanderbilt would later purchase, as well as the future Sexton Tract. In fact, what became the Sexton Tract was very important to Bard, and later his son, Samuel, because it contained a natural wharf along the Hudson that they used to ship goods downriver to New York City. Today, this wharf is known as Bard Rock. David Hosack, the estate’s owner after the Bard family, died in 1835, and his heirs held on to his Hudson Valley estate for a few years before dividing it. In 1837, they deeded the 64.22 acres of the Sexton Tract to Hosack’s widow, Magdalena Coster Hosack. They sold the more southern part of the estate, that later became Vanderbilt’s, to Walter Langdon Sr. in 1840. This is how the estate came to be split.

Following Magdalena Coster Hosack’s death, the Hosack family sold the Sexton Tract to a Poughkeepsie newspaper owner named Augustus Cowman in 1842. His ownership lasted until 1853. Subsequent owners of this piece of land were Joseph R. Curtis (1853-1861), Sylvie Drayton Kirkpatrick and her heirs (1861-1889), and finally Samuel B. Sexton (1889-1905).

So, what did this piece of land look like when Vanderbilt reunited it with Hyde Park in 1905? Several buildings existed on the property, including a coach house, pump house, boathouse, farm buildings, greenhouses, and cottages for the coachman and estate superintendent. Notably missing from this list of structures is a residence for the estate’s owner. The house constructed by Samuel Bard in the early decades of the 19th century had been replaced by an Italianate mansion during Joseph Curtis’s ownership. In 1899, however, this mansion burned and was never reconstructed. The landscape in 1905 was mostly open, with a woodlot bordering the Vanderbilt property. Deliberate tree plantings dotted the landscape and there may have been an orchard near Bard Rock.

The Curtis/Sexton house that burned in 1899. (Cultrual Landscape Report for Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, Vol. 1. 1992)

After Vanderbilt reunited the Sexton Tract with the rest of his estate, he adjusted the drives on his property and constructed a new north gate (today’s exit gate). He removed all of the existing structures except for the boathouse. Mr. Vanderbilt now had access to the natural wharf at Bard Rock, of which he took full advantage. He would often travel to Hyde Park via yacht, mooring his vessel in the deep waters just next to Bard Rock and coming to shore aboard a smaller craft. A yacht, especially a Vanderbilt yacht, was a big boat so it had to be moored in the deep water in the middle of the Hudson, rather than the shallows near the shore.

Though evidence of the Sexton Tract is scant, what remains are interesting clues to the former life of this section of Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, which holds some of the park’s most interesting landscape features. While we didn’t discover any hidden treasure, this little adventure was a great reminder that our National Parks and Historic Sites are layered, complex landscapes full of natural beauty and historic significance.

Bibliography

Birnbaum, Charles A., Patricia M. O'Donnell, and Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Ph.D. Cultural Landscape Report for Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, Volume 1: Site History, Exisitng Conditions, and Analysis. Boston: National Park Service Division of Cultural Resource Management, 1992.