PARC, NPS

The Significance of the Panama Canal The construction of the Panama Canal (1902-1914) represented one of the worlds' most ambitious engineering feats. During the 19th century, international trade depended heavily on shipping to transport different countries' goods around the world. Ships traveling from New York City to San Francisco had to sail all the way down the east coast of North and South America, navigate around Chile's dangerous Cape Horn and then come back up the west side of the two continents. Eager to connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and to reduce this lengthy travel time, engineers identified the narrow Panama isthmus in Central America as an ideal location for an interlocking canal. In the 1880s, a French construction company attempted to build the canal as a business investment opportunity. The overwhelming construction project required thousands of men to dig eleven miles with primitive tools through disease-ridden swamps. Under the French company, the project lagged on for years, plagued with engineering disasters, rampant diseases and financial mismanagement. When U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt took office in 1901, he identified the canal as critical to the American people and established it as a top national priority. Through various political and financial events, the U.S. took over the construction in 1902. The U.S. assigned a new construction commission to improve both the engineering methods and the significant health issues related to the canal construction. Under American supervision, the canal construction was finally successful and the Panama Canal officially opened for shipping business in 1914. For many Americans, the Panama Canal represented the country's ability to get the job the done.

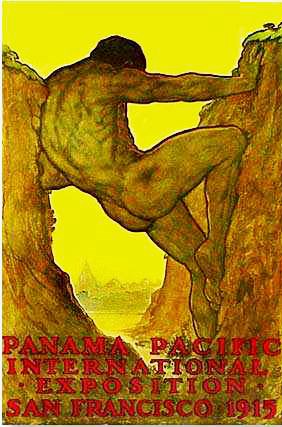

PARC, NPS San Francisco as the next world's fair location

PARC, NPS

Making the Exposition Possible: Politics & Location Once created, the Panama Pacific Exposition Company and its board of directors, made up of some of San Francisco's most powerful and influential politicians' and businessman, got down to the task of making the fair a reality. They launched successful public and private fundraising efforts to support their international fair proposal. By this time, Washington DC, Boston and New Orleans were also lobbying Congress to be the host city for this fair. After an aggressive public relations campaign and the promise that the city would not accept any federal funding, San Francisco was awarded the final bid. On February 15, 1911 President Taft sign a resolution designating San Francisco as the official home of the future Panama Pacific Exposition and after the ground-breaking ceremony, President Taft called San Francisco "the city that knows how." With only four years remaining to design and build the entire fair, the directors of the company had an enormous task ahead of them. Their most significant decision was where to hold the fair. After considering many sites, including Twin Peaks, Lake Merced, the Mission, Golden Gate Park and Oakland, the company chose the largely-undeveloped Harbor View area (now the Marina) because it afford spectacular views of the Bay while still close to many neighborhoods. This waterfront location still came with challenges. The company would have to purchase over 75 city blocks and demolish over 200 buildings and they would have to fill in the marshland. Most important politically, the Panama Pacific Exposition Company would need to gain permission from the U.S. Army to build on both the Presidio and Fort Mason land.

Photo courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Photo courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The Country's Best Designers for the Fair The Panama Pacific Exposition Company assembled a team of the county's best and most experienced architects, designers, landscape architects, artists and engineers to create a design worthy of an international exposition. The exposition's chief architect was George W. Kelham, the San Francisco architect who had experience with the design the Paris Exhibition of 1900. Other famous architects involved in the master planning and building design included Bernard Maybeck and the influential New York firm of McKim Mead &White. John McLaren, the designer of the Golden Gate Park, was the master landscape designer. Kelhman and his architectural team laid out a classic, symmetrical design of eight large exhibition palaces clustered around decorative courts and avenues. The Palace of Machinery on the east and the Palace of Fine Arts on the west flanked the palaces on either side. The shining centerpiece was the Tower of Jewels, the decorative Italianate tower covered in multicolored cut glass. The international and national pavilions, as well as the race track, were located on the Presidio and the Amusement Zone was located on Fort Mason property. The creation of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition required the construction of a grand and elegant city that was only to last eleven months. Almost all of the fair buildings were constructed in wood frame and covered in a material composed of gypsum (plaster of Paris) and hemp, was designed to look like Italian marble. As the Chief of Color, Jules Guerin designed a palette of soft and harmonious paint colors that would enhance the imitation travertine. In studios, commissioned artists and workers constructed over 1,500 individual sculptures with wood, wire and the faux marble material. The fair's ongoing vegetation and landscape needs were intensive. The landscape architects had to ship in over 30,000 full-grown trees and thousands of shrubbery to turn the acres of sand dunes and landfill into sophisticated, large-scale gardens. Once fully constructed, the entire exposition covered over 600 acres and came to a total construction cost of $15 million dollars. Due to the excellent planning and cooperation from San Francisco and its labor organizations, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition opened to the public both on-time and within budget –a first in world's fair history.

PARC, NPS For More Information: To see more photos and maps, please visit the Panama-Pacific International Exposition home page. |

Last updated: October 17, 2016