Metal is typically defined as a solid material that is hard, shiny, malleable, fusible, and ductile. In short metal is known to be resilient and valued for its strength and durability. But the reality of metal is so much more. Chemically most metals are inherently unstable. Metals begin to weaken the second they are formed because they are a product of mixed elements, or an alloy. This means that metal will always try to exist at its easiest form because it is continuously reverting to its more stable elements. Steel will want to become one pile of iron and one pile of carbon; this is decay through corrosion.

The visible proof of corrosion, and the discoloration we see, is a reaction the metal surface area is having with the oxygen in the air creating the oxide layer we call “rust”. So even though we don’t like to see rust, it is the natural process of the metal trying to return to its original form.

The rate at which rust appears and the subsequent metal decay happening are based on a few factors including but not limited to moisture content in the atmosphere and soil, the level of acidity in soils or air, and the presence of salt, like being near a bay or the ocean. Some metal alloys have a mix of elements that naturally resist rusting.

Most preservation actions are simply the steps we take to slow the inevitable decay of an object. We try and maintain storage temperatures, locations of storage, and the humidity of the area for specific objects. How long can we stop this process?

In 1985, the GGNRA excavated Black Point Battery at Fort Mason. The site had been widely known to have been occupied for over 200 years by various colonizing forces and even longer use has been attributed to the native Californians. As far back as 1797 it was called Bateria San Jose by the Spanish and then “Bateria De Yerba Buena, a name also used by the Mexican Army. This area of Fort Mason always commanded excellent defensive views of anything coming into the San Francisco Bay, so naturally every country built and staffed a battery here. During the excavation archeologists discovered many metal artifacts. Metals a of specific type and value, and due to their inherent instability, need to be preserved quickly. What could be done?

Many conservators were asked about methods of conservation. Although the view at the time was that nothing would stop deterioration because all metal will eventually decay, there were chemical treatments available that could in essence encase the object from further environmental destruction. Unfortunately, these methods were cost prohibitive, and their use and effect on the integrity of the artifact, has been questioned over time.

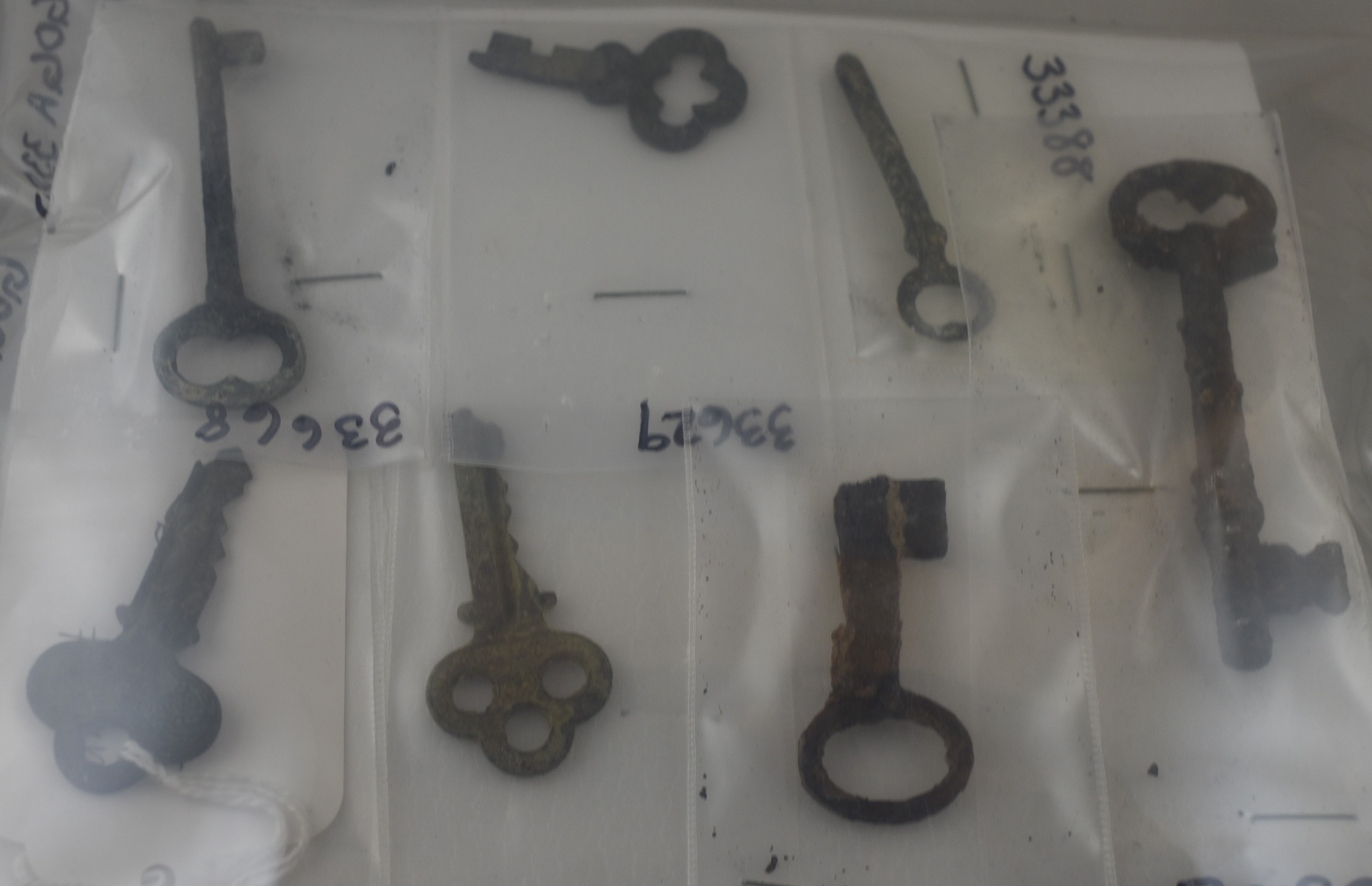

During the Crissy Field Restoration project in 1999, several American era landfills were excavated, revealing even more metal artifacts. This time the park decided to try and preserve select small metal pieces through anoxic storage. These items were bagged and sealed, afterward the oxygen in the bag was replaced with nitrogen, an inert gas. This method will slow decay as the metal surface will not have the opportunity to react to oxygenated air. Can anoxic storage be the answer to rust and allow us to save these artifacts for future study? Will there be another technique in the future that better prevents rust from forming but doesn’t require the item to be bagged? It does seem to combat the major chemical issues that affect the ability to store it. Only time will tell if this process makes these small metal artifacts easier to retain and study further.

Despite the park’s best efforts at implementing these conservation techniques, in addition to the basic preservation strategy of trying to maintain a stable environment, the result is that many of these recovered metal artifacts are deaccessioning themselves (or removing themselves from the collection by natural process). Did we learn what we need to with the techniques and equipment available at the time? Will thorough documentation of these objects today be enough to inform a researcher of their cultural, or historical value after the item succumbs to time, temperature, and metal’s chemical nature?

It’s good to remember that rust is natural and signifies the breakdown of these metals to their original form. It could be that that there is beauty in rust. An acceptance, if you will, that all things will eventually break down regardless of whether we are ready for it to or not. Maybe there is a lesson in (not) trying to save everything? What metal objects need to be kept and for how long? It would be nice to know why the object was here, what it may have been used for, and how that affected society at the time, but will we learn it before decay takes it from us? Could it be that the idea, the wonder, and the mystery of things lost can inform the value of the time we have today to research and understand what we find? Who knows, I was just photographing rusty artifacts I found in the archeology lab.

What do you see when looking at a rusty thing?