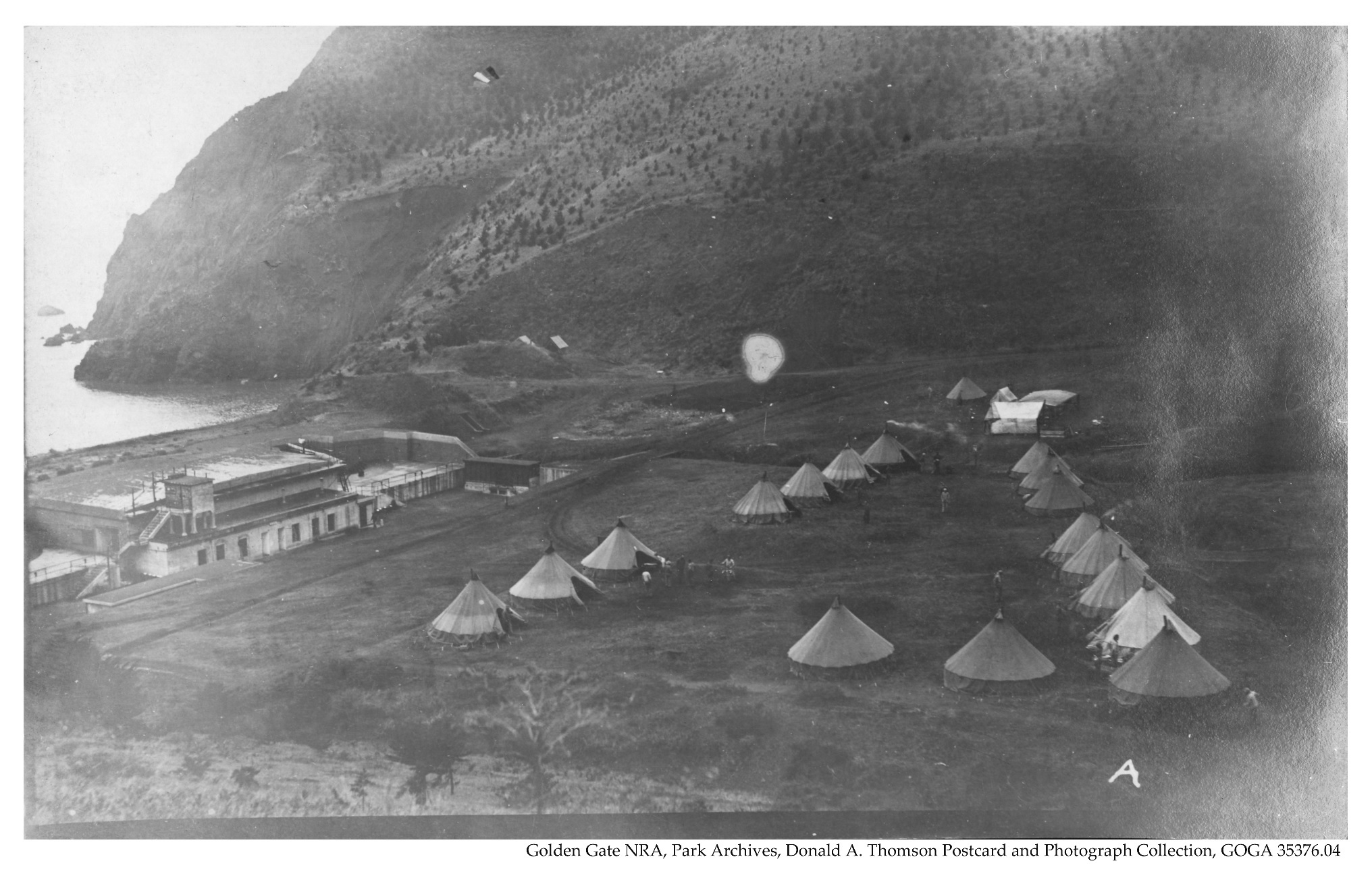

Beginning in the mid 19th century, the Army established one of the nation’s earliest and most important coastal defense systems in San Francisco’s Presidio and the Marin Peninsula with artillery batteries active through the Civil War and both World Wars. Built along the coast, Forts Baker and Barry are home to several batteries, now disarmed. Batteries were strategically nestled along the coastline to monitor shipping traffic and ensure the area’s safety against naval attacks. These coastal establishments offered exceptional vantage points and panoramic views of the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay for defensive firing lines and communication, but the natural topography of low coastal scrub and grasslands exposed the batteries to relentless sea winds. In such a bare and windswept landscape, the Army’s defenses were visible and vulnerable to approaching enemies at sea or via aerial attacks.

By the 1880s, the Army started planting blue gum Eucalyptus and trees native to California's central coast, the Monterey Cypress and Monterey Pine, to conceal, manipulate, and beautify the exposed and steep terrain around harbor defenses. Blue gum made its first appearance in California when Australians brought seeds during the Gold Rush era in the 1850s. It was initially planted as an ornamental tree and later for timber due to its quick growth and towering heights of up to 250 ft. Domestic lumber was expected to fall into short supply, but Eucalyptus proved less than ideal for timber as it cracked when dry. With the exceptionally moist air of the Bay Area’s fog belt and lack of any predators that it usually had to contend with in Australia such as beetles, moths, and scale insects, Eucalyptus thrived.

In 1890, the Army began expanding harbor defenses and entered into the Endicott-Taft modernization period. This era set in motion several changes such as the establishment of more harbor defenses, the redesignation of Lime Point Military Reservation to Fort Baker in 1897, and drastic landscape development to protect and beautify the topography. Established in 1885 under Secretary of War William Crowninshield Endicott, the Endicott Board made recommendations to plant various non-native trees and ground covering iceplant to transform the landscape around the Army’s defenses. With its quick growing ability, iceplant was used to stabilize sandy soil around battery parapets, planted on rooftops for camouflage, and provided a more diverse ground cover to the exposed and windswept slopes. Iceplant’s bright green color and distinct pink and white flowers dotted the hillsides, making artillery batteries even more conspicuous. To prevent further vulnerability, Eucalyptus was planted as screens to conceal the defenses. Eucalyptus served many important purposes including draining wetlands for building development, windbreaks, stabilization against landslides, bordering roads, and establishing perimeters.

In addition to the Army’s landscaping at harbor defenses, the Presidio in San Francisco became one of the most extensive Eucalyptus plantings where blue gum makes up roughly 42% of the forest. The plantings were inspired by Army Major W.A. Jones’ 1883, “Plan for Cultivation of Trees upon the Presidio Reservation”, that outlined beautifying the Presidio with trees including ornamental Eucalyptus. This became possible when in 1889, Senator Leland Standford introduced an amendment to an appropriation bill for landscaping improvements to the roads and walkways of the Presidio, Fort Mason, and the national cemetery. The appropriation provided these areas with the funds to ornament the area with trees grown in the Presidio nursery. Over 51,000 Eucalyptus saplings and over 19,000 of each Monterey Cypress and Monterey Pine species were planted in the Presidio to provide windbreaks and prevent erosion near the newly developed roads, houses, and military buildings.

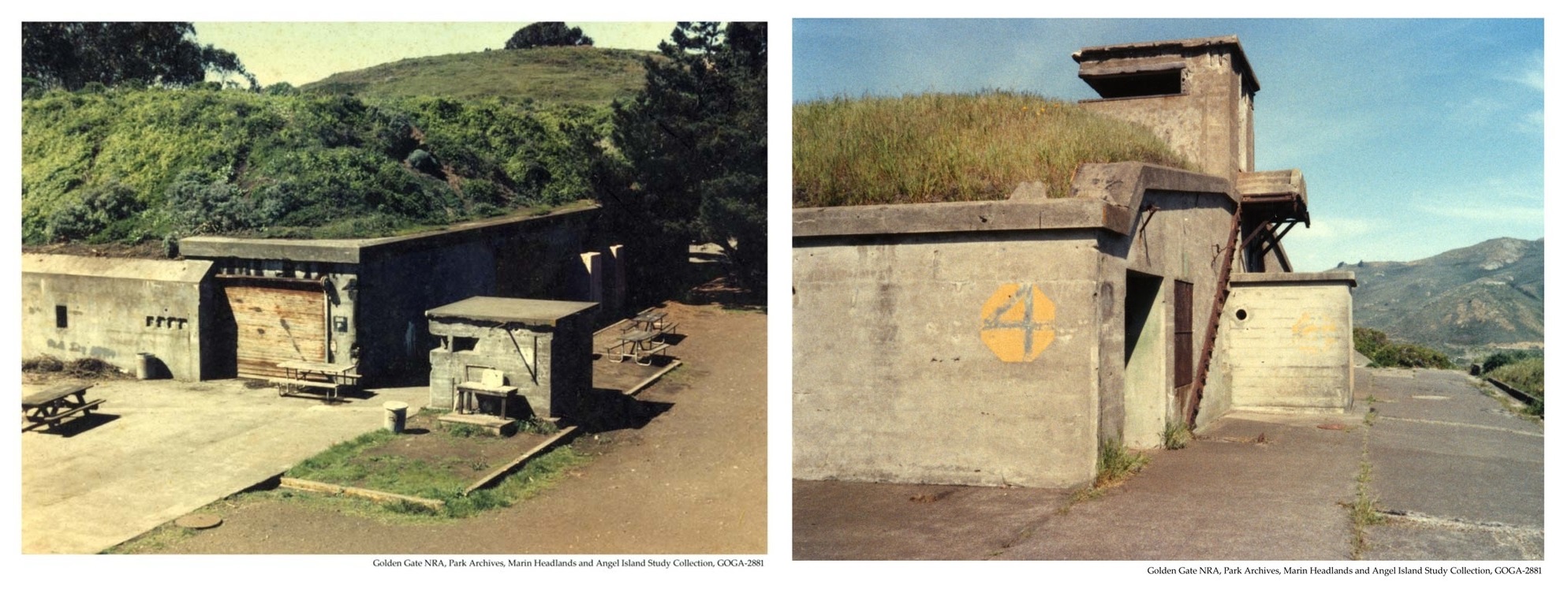

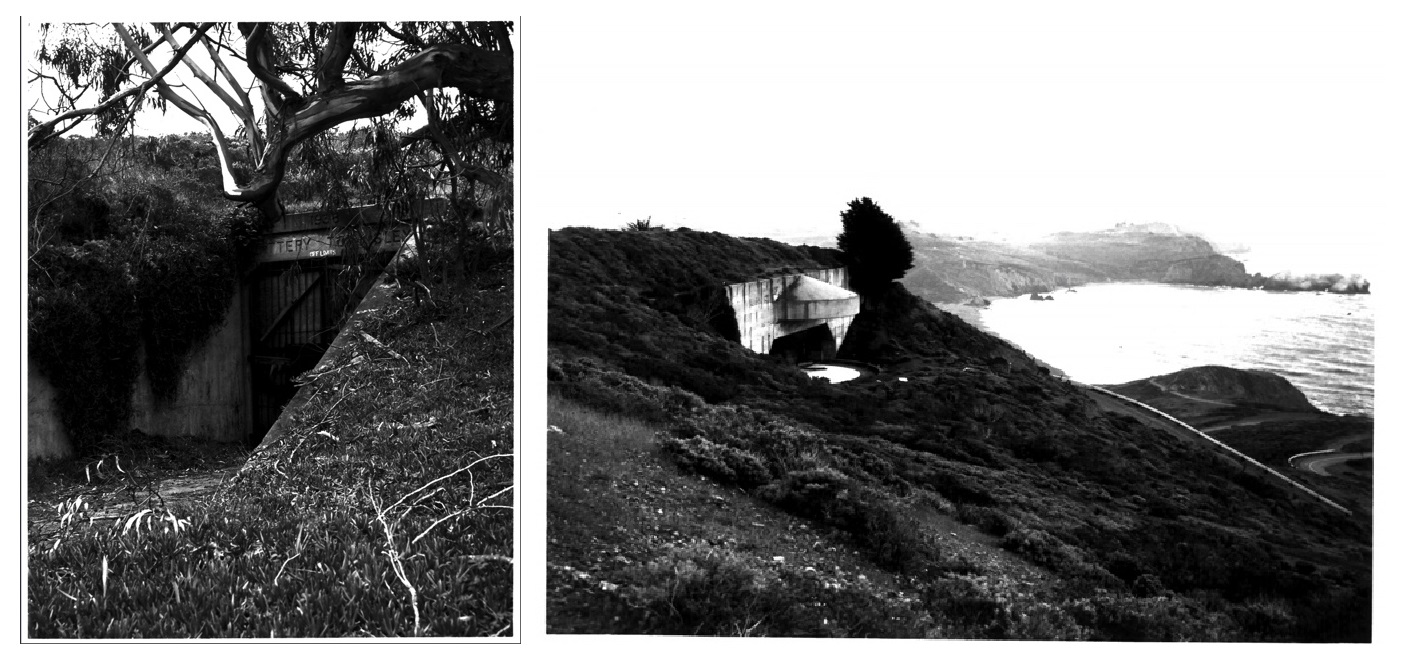

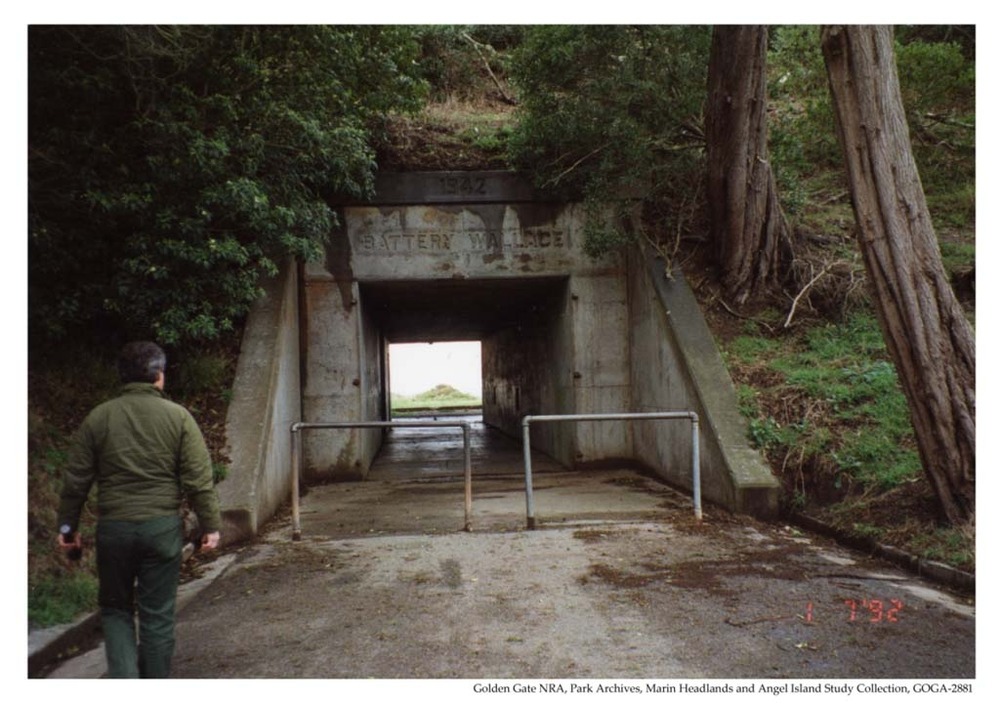

In addition to the Army’s landscaping at harbor defenses, the Presidio in San Francisco became one of the most extensive Eucalyptus plantings where blue gum makes up roughly 42% of the forest. The plantings were inspired by Army Major W.A. Jones’ 1883, “Plan for Cultivation of Trees upon the Presidio Reservation”, that outlined beautifying the Presidio with trees including ornamental Eucalyptus. This became possible when in 1889, Senator Leland Standford introduced an amendment to an appropriation bill for landscaping improvements to the roads and walkways of the Presidio, Fort Mason, and the national cemetery. The appropriation provided these areas with the funds to ornament the area with trees grown in the Presidio nursery. Over 51,000 Eucalyptus saplings and over 19,000 of each Monterey Cypress and Monterey Pine species were planted in the Presidio to provide windbreaks and prevent erosion near the newly developed roads, houses, and military buildings.Across the Golden Gate Bridge at Fort Baker, home to Battery Cavallo, Battery Yates, and Battery Duncan, Eucalyptus and Monterey Cypress trees were strategically planted to conceal water tanks in addition to the battery itself. Across the peninsula at Fort Barry is the oldest stand of Eucalyptus planted by the Quartermaster. In addition to blue gum, Black Acacia (Acacia mearnsii), Monterey Pine, Monterey Cypress, and iceplant were used to establish perimeters and conceal Fort Barry’s Battery Alexander and Battery Smith-Guthrie exposure.

The traits that initially made Eucalyptus appealing first became problematic for the Army and residents when trees began to block scenic views at the Fort Mason parade grounds and several coastal batteries. Stands of Eucalyptus planted c.1915 at Battery Kirby, for example, had expanded beyond original plantings and blocked strategic firing lines. Extensive tree removal in these areas began in the 1930s, in an effort to reestablish the obstructed views. Other original Army plantations continued to expand rapidly and soon the peeling deciduous bark and shedding leaves characteristic of blue gums made it difficult for native plants like lupine and insects such as the Mission Blue Butterfly to inhabit the debri-heavy forests.

The invasive nature of blue gum, iceplant, and other non-native plant species resulted in the crowding out of native plant wildlife in the former Army occupied areas of San Francisco and the Marin Headlands. In addition to its invasive character, Eucalyptus also proved to be a fire hazard as witnessed in the devastating Oakland Tunnel Fire of 1991 and 2004 Mt. Tam fire. Loose strips of bark and old, oily leaves are extremely flammable and spread fire even quicker through a forest canopy.

Around the time of land transfer from the Army to the National Park Service (NPS) in 1993-1994, NPS initiated a change in conservation efforts including thinning out forests, cleaning up tree debris, and scaling back many invasive plants to encourage native habitats. There have been ongoing arguments for decades in favor of getting rid of Eucalyptus to prevent wildfires, but removal is costly and labor intensive. Today, efforts are made to protect Eucalyptus plantings that express cultural and historic significance balanced with the necessary elimination of overgrowth and persistent expansion. Although it has greatly impacted the area’s ecosystem, it is undeniable that blue gum Eucalyptus was essential in establishing the Bay Area landscape as we know it today. Even as a non-native to California, Eucalyptus is an iconic part of the west coastline and a significant piece in the history of our landscape.

If you would like to learn more about the Army’s development of forts as well as landscape changes during the occupation, check out these reports:

Cultural Landscape Report for Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite, Vol. I: Site History

Cultural Landscape Report for Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite, Vol. II: Existing Conditions Through Treatment

If you’d like to learn more about Bay Area tree conservation and land management:https://www.nps.gov/pore/learn/management/upload/firemanagement_fireeducation_newsletter_eucalyptus.pdf